Most electricity is produced by burning fossil fuels. Economic variable electricity can be produced to match demand because most fossil plants have low capital costs and high operating costs. The cost of electricity does not increase rapidly for power plants operating at part load when the operating cost is the primary cost. Concerns about climate change require going to electricity generating technologies that do not emit carbon dioxide such as nuclear, wind and solar. These technologies have high capital costs and low operating costs (Table 1); thus, the cost of electricity increases rapidly if these capital intensive plants are operated at part load. Because total energy costs for society are typically close to 10% of the gross national product, significant increases in energy costs implies significant decreases in the standard of living.

In deregulated markets the large scale use of solar and wind results in electricity price collapse at times of high wind or solar input when electricity output exceeds demand. Collapsing revenue limits the economic use of solar, wind, and ultimately nuclear. A Firebrick Resistance-Heated Energy System (FIRES) is proposed2,3 to limit electricity price collapse at times of high wind and solar output by converting excess low-price electricity into high-temperature stored heat that can be used as a substitute for fossil fuels by industry and to generate electricity at times of high prices.

A minimum price of electricity is created near that of the price of fossil fuels used by industry. It is a mechanism to better utilize capital-intensive generating assets.

The paper (1) defines and characterizes applications for FIRES; (2) describes FIRES technical performance characteristics; (3) analyzes implications of large-scale deployment on electricity markets; and (4) estimates capital costs. The paper reports on near-term applications such as heat to industry and long-term options such as coupling FIRES to gas turbines.

Electricity markets

In deregulated electricity markets, electricity generators bid a day ahead on the price that they are willing to sell electricity into the market—typically for each hour of the day. The grid operator accepts electricity bids up to the expected electricity demand for each hour. The bid ($/MWh) with the highest electricity price that is accepted sets the price for that hour and everyone who bids below that price gets the same price. Historically most electricity has been generated using fossil fuels; thus, the price set for each hour was set by the fossil fuel plant operating at that hour with the highest operating costs (Table 1). The markets have a variety of other mechanisms to assure reliable electricity and remain within the technical constraints of the electricity grid.

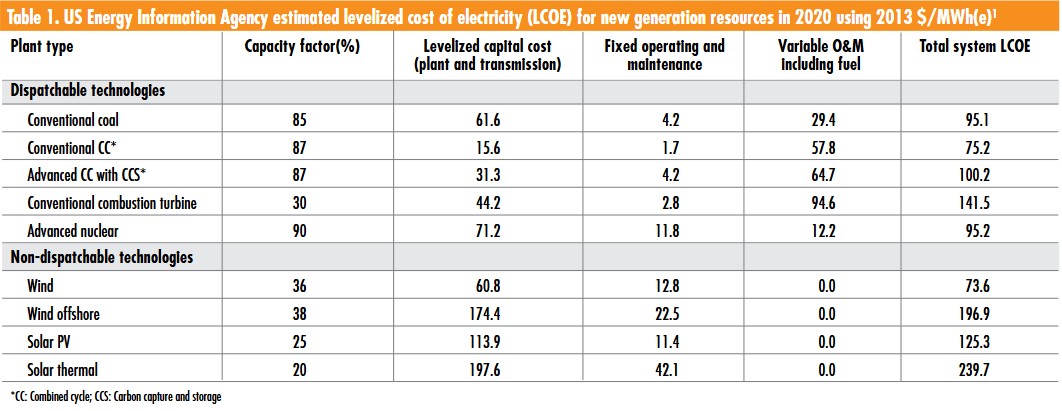

In a perfect market, wind and solar will bid zero dollars per megawatt hour (Table 1)—their variable operating and maintenance costs. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Future of Solar Energy4 study provides an examination of the solar option and the challenge of moving from an electricity grid dominated by fossil fuel generation to a low-carbon grid. Figure 1 shows market income for solar plants with increased use of solar. The average price of electricity received for the first few solar plants that are built is above the average yearly electricity price because the electricity is produced in the middle of the day when there is high demand and the prices are high. As more solar plants are built, electricity prices at times of high solar output collapse; thus, solar revenue collapses as solar production increases. This limits unsubsidized solar capacity to a relatively small fraction of total electricity production even if there are large decreases in solar capital costs.

Figure 1. Solar PV market income and average wholesale electricity prices versus solar PV penetration.

At the same time there are only small changes in the average price of electricity. Other power plants are required to provide electricity at times of low solar output—but these plants operate for fewer hours per year. Investors will not build new power plants to meet this need unless the price of electricity increases at times of low solar output to cover costs of a power plant that operates only part of the time.

The same effect occurs with wind. Recent studies have quantified this effect in the European market.5,6 If wind grows from providing 0% to 30% of all electricity, the average yearly price for wind electricity in the market would drop from 73 €/MWe (first wind farm) to 18 €/MWe (30% of all electricity generated). There would be 1,000 hours per year when wind could provide the total electricity demand, the price of electricity would be near zero, and 28% of all wind energy would be sold in the market for prices near zero.

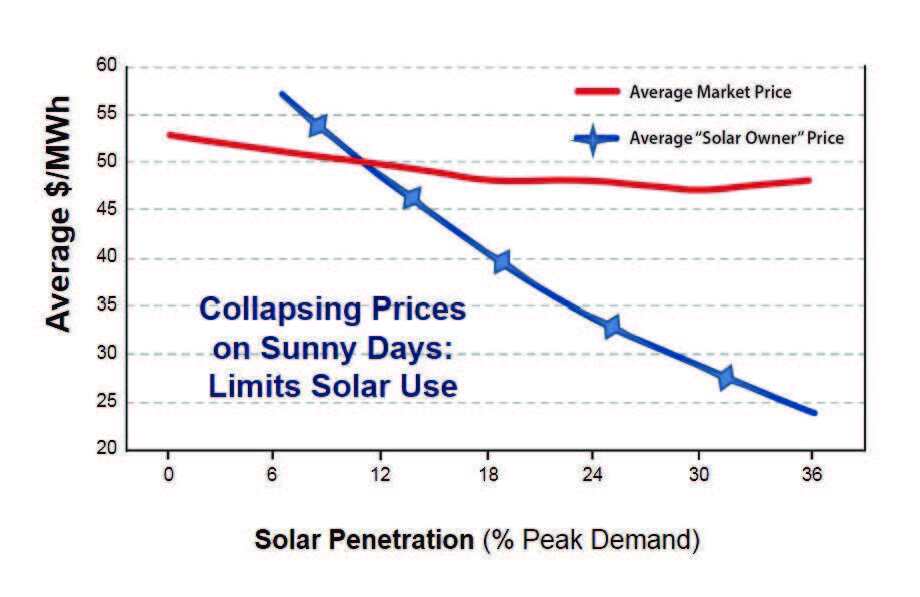

To use a real example, Figure 2 shows wholesale prices for electricity in western Iowa, a state with a large installed wind capacity. One can see negative prices enabled by wind subsidies on days of high wind conditions. When there are negative prices, the electricity generator pays the grid to take the electricity. Wind operators are willing to pay the grid to take electricity because their subsidies are tied to electricity produced. Without subsidies, prices would go to zero but not negative except under limited circumstances. In this specific example the price of electricity is less than the local industrial price of natural gas for over half the time.

Figure 2. Hourly wholesale electricity prices in Iowa over two years.

Analysis7 indicates that significant price reductions occur on a grid when solar provides over 10% of all electricity produced, wind provides over 20% of all electricity produced, and nuclear provides over 70% of all electricity produced. The different levels of solar, wind and nuclear penetration before significant revenue collapse reflects the relative mismatch between electricity production for each of these technologies and demand. There is a large literature on the other market effects of adding solar and wind to the grid8,9 and limits on use of electricity storage to address this challenge.10,11,12

The revenue collapse is a consequence of going from low-capital-cost high-operating-cost fossil systems to high-capital-cost low-operating cost solar, wind and nuclear systems. Revenue collapse at times of high solar and wind input favors the use of low-capital-cost high-operating-cost fossil fuel electricity generation at times of low wind or solar output. This expanded the use of coal in Germany and natural gas in the United States as renewables are added to the grid.

Societies can choose to subsidize particular energy systems for social reasons but because energy is such a large fraction of the global income, this has large impacts on standards of living. What is required are low-cost methods to productively use low-operating-cost excess generating capacity when available to reduce electricity price collapse under high wind or solar conditions and thus expand use of low-carbon solar, wind, and nuclear electricity generating technologies.

FIRES for industrial heat

Technical description

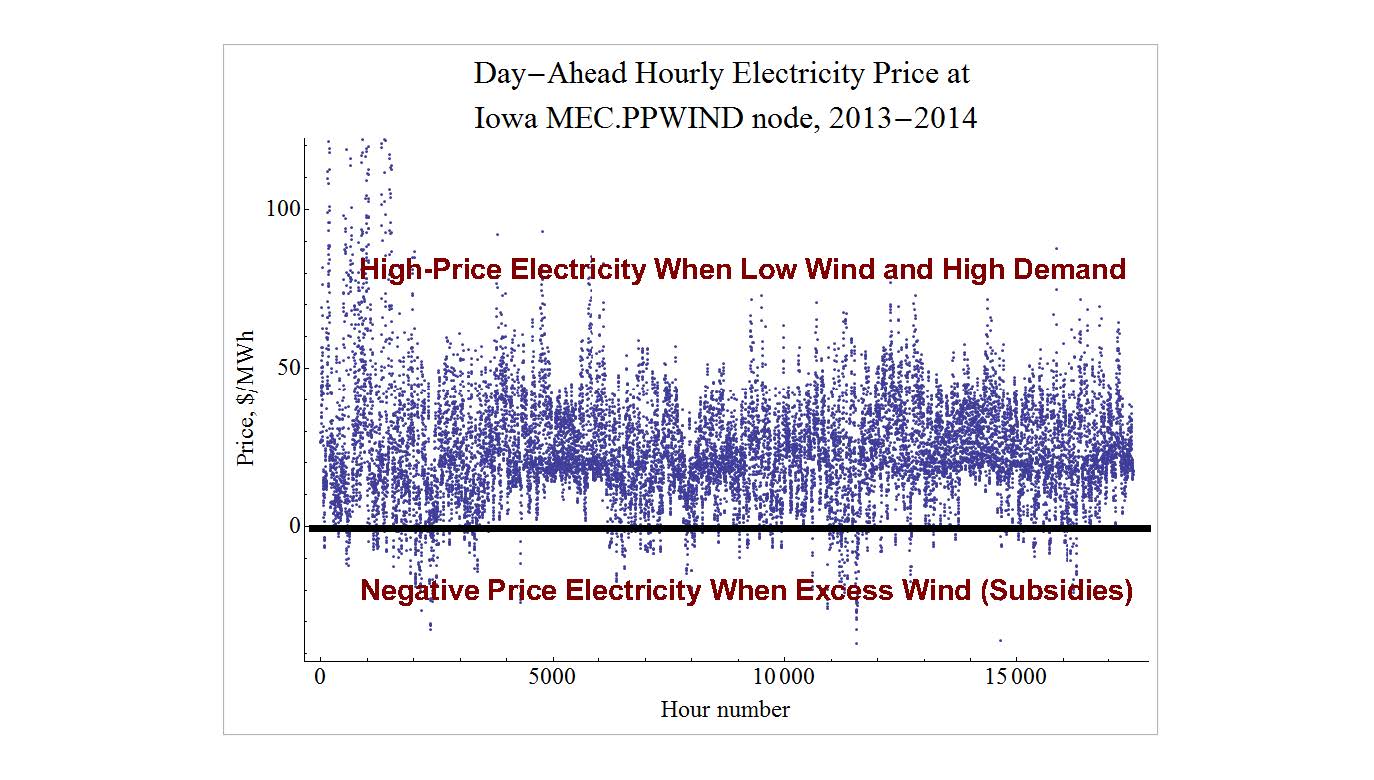

FIRES (Figure 3) consists of a firebrick storage medium with a relatively high heat capacity, density, and maximum operating temperatures up to ~1,800°C.2,3 The firebrick is “charged” by resistance heating with electricity at times of low or negative electricity prices. Low electricity prices are defined as electricity prices that are less than the competing fossil fuel—that is natural gas in the United States. Resistance heating is the lowest cost method to use electricity.

Figure 3. Configuration of FIRES coupled with an industrial process.

The firebrick, insulation, and other storage components are similar to high-temperature firebrick industrial recuperators. The ceramic firebrick is used because of its low cost and durability, while also having large sensible heat storage capabilities. If one allows a 1,000°C temperature range from cold to hot temperature, the heat storage capacity is ~0.5–1 MWh/m3.

The heat is recovered by blowing air through channels in the brick. The output of FIRES is hot air, which is heated or cooled as needed for the given application by adding natural gas heat or cold air, respectively. The required discharge rate is determined by the furnace hot-air requirements that FIRES is coupled to. FIRES is designed for specific groups of industrial customers. There are three performance characteristics of interest (Figure 4), each of which is largely independent of the other: storage capacity, charge rate, and discharge rate.

Figure 4. Independent performance aspects of FIRES.

Storage capacity: Storage capacity of FIRES is governed by the sensible heat capable of being stored in a volume of material over a chosen temperature range (minimum and maximum temperatures). The chosen temperature range and material will be determined by the needs of the industrial process. More firebrick will store more energy.

Charge rate: FIRES is charged by resistance heating. The charge rate will be determined by the electricity market. If the wind or solar resource combined with market demand drives prices down for only a few hours per day, high charging capacity will be preferred to capture the lowest priced electricity. If low price electricity is available for longer periods of time, lower charging capacity with its lower costs will be preferred. The type of electric resistance heating depends upon the peak temperatures. For less than 1,000°C, traditional low-cost resistance heating elements using nichrome wire or similar materials will be used—the type of heating elements in home toasters. Except for industrial applications, the wire is thicker and designed to operate at higher temperatures. Typical firebrick materials are made of aluminum, magnesium, and silicon oxides, cheap high-temperature materials that are insulators. The firebrick provides the electrical insulation for the heaters. For very high-temperature operations, conductive firebrick made of materials such as SiC may be used as the resistance heaters.

Discharge rate: Within FIRES, the nominal discharge rate is determined by the heat transfer from the hot firebrick to the air, which is a function of air channel geometry, fan power and other design features discussed in Section 3.4.

The heat losses in optimized systems will be below 3% per day. In addition to insulation, cold air flow into FIRES can be routed around and through the outer sections of the insulation and by electrical leads to resistance heaters to pick up heat that is leaking from the system. This type of dynamic insulation recovers most of the heat leaking though the insulation and can result in extremely low heat losses if FIRES is operating on a daily cycle.

Operations

The heat input rate would depend upon resistance heating capability, unused heat storage capacity, and day-ahead projections of electricity prices.13 The price of electricity varies by the hour, thus electricity to heat the firebrick would be purchased when the prices were at their lowest given the constraint to maximize total kWh of electricity bought at less than the price of the alternative fossil fuel. This creates an incentive to oversize the electrical heaters to maximize electricity purchases when the price is low.

If FIRES is fully charged and the price of electricity is less than the comparable fossil fuels, the heaters would operate at the power level of the industrial furnace—avoiding the need for a second set of electric heaters to take advantage of low-price electricity to provide heat to industrial furnaces. In locations such as western Iowa, electricity prices are below natural gas prices for over half the time, implying electric heaters are on over half the time. With large-scale deployment, the minimum electric prices will follow fossil fuel prices much of the year. Because the industrial heat demand is larger than electricity production, it has the potential to absorb all low-price electricity. This is in contrast to other storage devices (pumped storage, batteries, etc.) that have “limited” storage capacity.

The owner of FIRES wants cheap heat—but does not care when heat is delivered. However, the electricity grid operator has a different perspective. Electricity to FIRES resistance heaters can be cut off in a fraction of a second without impacting heat delivered to the industrial furnace from the firebrick. Shutting down or turning on the FIRES resistance heaters can be used to stabilize the grid; thus, there are incentives for the grid operator to pay the FIRES owner to control when electricity is sent to FIRES resistance heaters.

Technology status

Firebrick with electric heating is used for low-temperature home heating in Europe and elsewhere. Some utilities offer a discount rate for electricity at night. At such times the firebrick is heated up to 600°C with electric resistance heaters. The hot firebrick then provides warm air when needed for room heating by blowing air through channels in the firebrick. Over 100,000 MWh of such heat storage capacity14 has been built with heat storage capacities under 100 kWh per unit. In the last several years there have been night discount rates on electricity in parts of China. This has resulted in development of similar units to provide hot air for heating water up to 85°C to provide hot-water heat and hot water for large apartment complexes. The larger firebrick heat storage units have capacities of 8 MWh. These units have peak firebrick temperatures of 850°C. There are large incentives to maximize peak firebrick temperature to minimize physical size and weight and thus enable building the units in factories and delivery of assembled units by truck. Such systems could be coupled together for smaller lower-temperature industrial applications. Lower-temperature FIRES could have been developed in 1920 if there had been a market.

FIRES has two major components: firebrick and electric heaters. The concept of FIRES has a great deal in common with firebrick recuperators used today in industry that were originally developed for open-hearth steel furnaces of the early-20th century. In these large systems, hot air was blown across the surface of molten pig iron (~1,600°C) to convert pig iron into steel by oxidizing the carbon in the pig iron. The hot off-gas from the furnace flowed through one of two firebrick recuperators in which the hot gas flows over cold firebrick, transferring heat to the bricks before exhausting to the stacks. Later, the direction of air flow through the system was reversed, such that cold air enters and flows through the now-hot firebrick, thereby preheating the air. The hot air from the recuperator was further heated with oil before going to the furnace. The air temperatures had to be maintained above 1,600°C to avoid freezing the pig iron and freezing the liquid metal surfaces. Firebrick recuperators are used today in the steel, glass, and other high temperature industries to recover heat to lower energy costs. There is a century of experience in operating industrial recuperators up to about 1,800°C.

Large-scale low-cost electric resistance heaters are an off-the-shelf technology with peak temperatures between 1,000°C and 1,200°C; but, there are tradeoffs between peak temperatures and heater lifetimes. There are multiple resistance-heater options at higher temperatures but the experience base is more limited and the costs are significantly higher. One option for low-cost very high temperature heaters is the use of conductive firebrick. Conductive firebrick is used in electric steel making processes at very high temperatures, but in a steel plant the conductive firebrick is under chemically reducing conditions and would not withstand the oxidizing environment of FIRES. There are alternative conductive firebrick options such as silicon carbide. We have initiated an experimental program to develop heaters for high temperatures using conductive firebrick as the resistance heating element, a potentially low-cost high-reliability heating system for this application. Unlike conventional resistance heaters, these heaters would literally be piles of conductive brick.

Editor’s note: See original article for section 3.4 Design Examples.

Economics

Two approaches2,3 were used to bound the costs of FIRES. The existing home heating variant (~100 kwh) of FIRES has retail prices as low as $15/kWh with a large spread in prices. Large home systems have about 100 kWh of storage capacity. For a typical industrial plant with 30 MW of heat input, FIRES would be sized to be over 100 MWh of storage capacity. Given the larger scale and avoiding markups for retail, the cost would be expected to be substantially less. The second approach was to price the components of fires from the electrical transformer to the firebrick. This yielded a price of $2.35/kWh that depending upon other factors implies an installed cost 2 to 4 times larger. These preliminary estimates result in an industrial FIRES system between 5 to 10 dollars per kWh.

Recent reviews12 of energy storage options have broken the cost of different energy storage systems into the cost of storage ($/kWh) and the cost of power ($/kW). The low cost of FIRES relative to other energy storage technologies is a consequence of two factors. First, firebrick is clay sent through a kiln with costs of $0.5–2/kWh of storage. For comparison, pumped hydroelectricity and underground adiabatic compressed air energy storage costs can be in the $10/kWh range but battery options are $200/kWh or more.

Second, FIRES’ power handling costs are low. Resistance heaters and the associated switches are cheap—a few dollars per kilowatt of power input. Resistance heaters can be designed to operate at any voltage including distribution voltages (22 kV and above) of the electricity grid and thus avoid added transformers and electrical losses. This is in contrast to other electricity storage technologies where power conversion capital costs are measured in $100s/kW. For pumped hydroelectricity and compressed air storage, those electrical systems must convert electricity from the grid into mechanical rotating energy and back requiring complex power control systems and motor-generators. For batteries, one must take AC electricity and convert it to low-voltage DC electricity and back. Resistance electric heating is the only low-capital-cost technology for consuming electricity and thus the only cost-effective option to use excess low-price electricity if it is available for short periods of time each day.

Preliminary economic analysis2 indicates that the most favorable locations for near-term FIRES deployment in the U.S. is in locations such as western Iowa (wind) where the payback is estimated to be between one and two years. The areas of FIRES economic viability will grow with additions of wind or solar.

Applications

Most of the world’s energy comes from burning fossil fuels in air that creates hot air—the same product as FIRES. As a consequence, FIRES couples to most existing energy production and use applications. FIRES economics are improved if it can operate year-round. The only two sectors of the U.S. economy capable of absorbing large quantities of energy at all times of year are the industrial sector and the market for electricity.

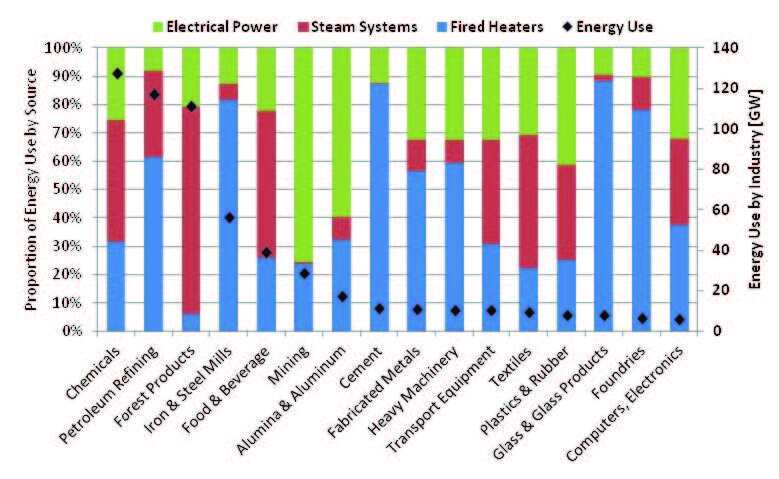

Figure 7. Energy use by U.S. manufacturing and mining industries for 2004.15

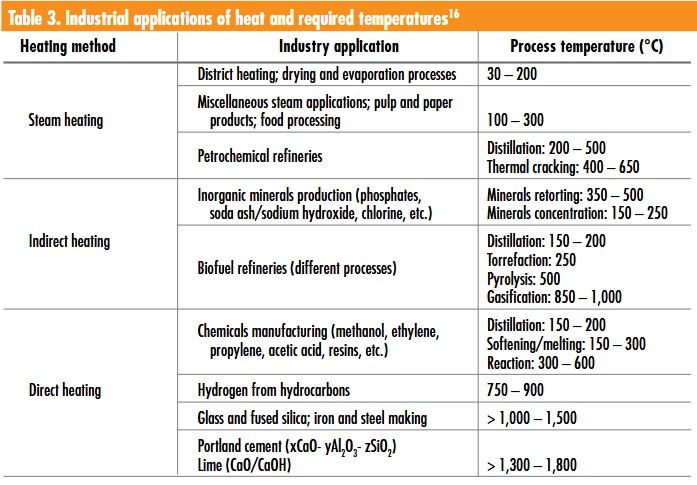

Figure 715 shows energy demand and heat demand by different sectors of the U.S. economy—the industrial markets for FIRES. Table 316 describes the different markets in terms of steam production, heating of other fluids through heat exchangers, and direct heating.

The largest market is indirect heating—producing steam or heating hydrocarbons (refineries and chemical plants) where heat is transferred through metallic heat exchangers with temperature limits typically between 500°C and 700°C. Current FIRES technology can meet these requirements. The glass, cement, and steel industries require very high temperatures and traditionally use direct heating with fossil fuels. There are incentives to operate FIRES up to 1800°C for some of these industries beyond just providing low-cost heat. For example, the production of cement and lime involves the high-temperature decomposition of CaCO3 into CaO and CO2. However, direct heating using fossil fuels creates a hot gas rich in CO2 that tends to drive the chemical reaction backward. If FIRES can provide some of the heat, the lower CO2 levels should reduce the energy required and increase the rate of decomposition of CaCO3.

FIRES can partly replace fossil fuels in various thermal electricity production systems in two different configurations. Coal, oil and natural gas plants provide variable electricity to the electricity grid. When low-price electricity is available and the fossil plant is not providing electricity, FIRES is heated. When there is high-price electricity, FIRES heat partly replaces the burning of coal, oil or natural gas to produce electricity. In this configuration FIRES acts as storage system. However, unlike batteries and pumped storage, if FIRES is depleted, fossil fuels can be used to assure electricity production capacity.

The alternative configuration is designing the thermal power system to couple only to FIRES; that is, FIRES is the only heat source. In this configuration FIRES is an electricity storage system equivalent to a pumped hydroelectric or battery system. Excess energy is stored as heat rather than gravitational potential or chemical energy. The round-trip efficiencies would be ~45% for steam cycles, ~40% for a simple gas turbine and ~60% for a combined cycle gas turbine. For the thermal power cycles (steam, supercritical carbon dioxide, etc.) where the heat source is operating at atmospheric pressure, FIRES could be built in large sizes for storage system outputs of hundreds of MWe. The gas turbine options are discussed in Section 5.

Siemens17 is beginning to develop a simple FIRES heat storage system for peak electricity production. At times of low electricity prices, air is heated to 600°C with resistance heaters and blown through a bed of crushed rock. The system is discharged by blowing cold air through the hot rock with the hot air being sent into a packaged steam boiler with the steam used to produce electricity. This storage system would be coupled to wind farms.

Last, there is potential market for FIRES coupled to photovoltaics (PV) for home or small industrial applications. PV panels are inexpensive but PV electricity for the grid is expensive because of the power conditioning and grid interface requirements.4 For areas with low-cost land, PV output could be directly coupled to the resistance heaters of FIRES without power conditioning. Unlike other electrical devices, resistance heaters do not need power conditioning. It is an analog to the century-old Great Plains windmills used to pump water where water output was variable and uncontrolled but sent to a cheap water tank that acted as the storage system. No detailed analysis of this option has been done.

The U.S. heat market includes the industrial, commercial, and residential sectors.18 While FIRES could be deployed in each of these sectors, the industrial sector is economically preferred. First, the individual heat loads are two to five orders of magnitude larger with large economics of scale. Second, industrial facilities operate year round whereas most commercial and residential heat loads are seasonal. This is important in two different contexts: (1) the seasonal heat demands of commercial and residential heat loads may not match when low-price electricity is available and (2) if FIRES operates for 300 days per year versus 100 days per year, the cost per unit of energy stored is reduced by a factor of three. The number of cycles per year strongly impacts economics. Third, the industrial heat market is larger than the electricity output of the United States.18 As a consequence the market for heat from FIRES is sufficient in size to consume all low-price electricity that may be produced. This is also true for other industrial countries such as Japan.

Editor’s note: See original article for sections: 4. Implications on Electrical Prices, and 5. FIRES Coupled to Gas Turbines.

Other implications

Beyond setting a minimum price for electricity that supports low-carbon generating technologies and provides heat to the industrial sector, FIRES may have other impacts on the electricity grid. Large-scale wind and solar results in large increases in grid and other electricity system costs4,9 separate from the costs of wind and solar generating systems. One major cost is the low capacity factors for transmission lines coupled to wind and solar because of low capacity factors for wind and solar production facilities (Table 1). In locations such as China where the major electricity load centers are far from the wind resources,33 there is a tradeoff. The capacity factors of the transmission lines can be increased by overbuilding wind capacity, but that lowers capacity factors for the wind farms. If there are local industries that can use heat, FIRES can dump some of that excess energy to the industrial sector, increasing local wind farm capacity factors while maintaining higher long-distance transmission capacity factors. Alternatively, FIRES can be coupled with a power generating system to store excess electricity to enable transport when the transmission lines have excess capacity.

Conclusions

The transition from a fossil-fuel based electricity system to a low-carbon electricity system is a transition from low-capital-cost high-operating-cost electricity generators to high-capital-cost low-operating-cost nuclear, wind and solar systems with low marginal generating costs. This has resulted in increasing numbers of hours in Europe and the U.S. with wholesale prices of electricity near zero—economically limiting the use of these low-carbon electricity sources. A low-cost technology is required to productively use excess electricity and raise the minimum prices for electricity at these times. FIRES converts low-price electricity into high-temperature hot air and stored heat to replace fossil fuels in industry—the only year-round market sufficient in size to absorb very large quantities of low-price electricity. Alternatively FIRES can be used to store electricity in the form of thermal energy.

The basic FIRES technology for many applications could have been developed and deployed in the 1920s. It is the change in the electricity market that creates the incentive to deploy FIRES. The estimated capital costs of FIRES to provide heat to industry is $5–10/kWh, below any other technology. That is because the heat storage media is pressed dirt that has gone through a kiln (firebrick) and electric resistance heating is the lowest cost device for using electricity. For some applications, FIRES can be built today. For other applications significant development is required.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Idaho National Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy for support of this work. This research is supported through the INL National Universities Consortium Program under DOE Idaho Operations Office Contract DE-AC07-05ID14517.

Read more: “Firebrick—A humble hero for stabilizing electricity markets“

*Open-access article first published in The Electricity Journal 30 (2017) 42–52 (http://dx.doi/10.1016/j.tej.2017.06.009). Excerpts republished under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/BY-NC-ND/4.0)

Cite this article

C. Forsberg, D. C. Stack, D. Curtis, G. Haratyk, and N. A. Sepulveda, “Converting excess low-priced electricity into high-temperature stored heat for industry and high-value electricity production* ,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2018, 97(3): 40–47.

About the Author(s)

Charles Forsberg is principal research scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and executive director of the MIT Nuclear Fuel Cycle Project. Daniel C. Stack is Ph.D. candidate at MIT; Daniel Curtis is Ph.D. candidate at MIT; Geoffrey Haratyk received a Ph.D. from MIT and now works for PSEG; and Nestor Andres Sepulveda is Ph.D. candidate at MIT. Contact Forsberg at cforsber@mit.edu.

Issue

Category

- Energy materials and systems

Article References

See original open-access article for references: The Electricity Journal 30 (2017) 42–52 (http://dx.doi/10.1016/j.tej.2017.06.009).

Related Articles

Market Insights

Engineered ceramics support the past, present, and future of aerospace ambitions

Engineered ceramics play key roles in aerospace applications, from structural components to protective coatings that can withstand the high-temperature, reactive environments. Perhaps the earliest success of ceramics in aerospace applications was the use of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) as thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) on nickel-based superalloys for turbine engine applications. These…

Market Insights

Aerospace ceramics: Global markets to 2029

The global market for aerospace ceramics was valued at $5.3 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.0% to reach $8.2 billion by the end of 2029. According to the International Energy Agency, the aviation industry was responsible for 2.5% of…

Market Insights

Innovations in access and technology secure clean water around the world

Food, water, and shelter—the basic necessities of life—are scarce for millions of people around the world. Yet even when these resources are technically obtainable, they may not be available in a format that supports healthy living. Approximately 115 million people worldwide depend on untreated surface water for their daily needs,…