Bootstrap origin stories have become a staple of the corporate history of many of the biggest names in the tech sector today. Ever since Bill Gates started Microsoft in his father’s garage, we have been in love with the idea of the microentrepreneur who starts from close to zero and builds a technology empire.

A look at the ceramic industry in Israel presents us with an entire country in that startup–upstart mode. Its population is still more than a decade away from hitting the 10 million mark, and its human capital for ceramic ventures is constrained. But by courting bilateral strategic partnerships and recruiting industry talent from abroad, Israel is determined to advance toward ambitious goals in ceramic research, development, and commercialization.

It is working on adding to its home-grown talent, as well. A government report (www.mfa.gov.il) based on Central Bureau of Statistics data found that between the 1989–1990 and 2011–2012 academic years, higher education enrollment rose from 88,800 students to 306,600 students. But the report noted that the most common courses of undergraduate study are in the humanities and social sciences. Graduate students gravitate toward the humanities, business, and management; only at the doctoral level do natural sciences and mathematics predominate.

There also is a gender gap, the report found, and one that some might find surprising: 66 percent of women will pursue an undergraduate degree, as opposed to just 53 percent of men. Perhaps with that in mind, the government is actively promoting women’s increased participation in STEM research and development via the Ministry of Science and Technology’s Council for the advancement of Women in Science and Technology. Its work extends to Israeli cross-border efforts with the European Union.

For now, from universities and research institutes to commercial enterprises, if Israel were dependent exclusively on domestic human resources, it would be too short-staffed to achieve its science and technology ambitions.

To address the labor shortage, the government has made a public commitment to doubling high tech employment over the next decade. In its 2017 annual report (www.economy.gov.il), the Israel Innovation Authority noted that just 8.3% of salaried employees work in the technology sector and set a target of 500,000 technology employees by 2027. Among the strategies outlined in the report: “Expanding spheres of employment in hi-tech, including integration of women, members of the Arab sector and Ultra-orthodox Jews in the workforce, along with veteran engineers above the age of 45.”

Military and market might

But there is another factor constraining research, development, and commercialization in technology in general and ceramics in particular: the demands and priorities of the well-financed defense sector. The CIA World Factbook notes that military expenditures represent 5.62 percent of Israel’s GDP.

“The Israeli market is quite small,” says the Israel Ceramic & Silicate Institute’s (ICSI) Zvi Cohen. “And the defense and military industry takes quite a large percentage of the usage of ceramic material. For civilian uses, it is much lower, and usually it is targeted for abroad and not for the Israeli market.”

To the extent that research activities are always influenced by the funding available to support them, this focus on defense is felt even at the academic level. Prof. Shmuel Hayun of the Department of Materials Engineering at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev reflects on the programmatic impact of what the funders want to finance.

“One of the major things that I’m working on since my master’s degree is armor-based materials such as boron carbide,” he says. “This stems from the need of the Department of Defense in Israel.” The project was launched more than 20 years ago by his former advisors, Professors Moshe Dariel and Nachum Frage. Hayun and Frage are still working on it.

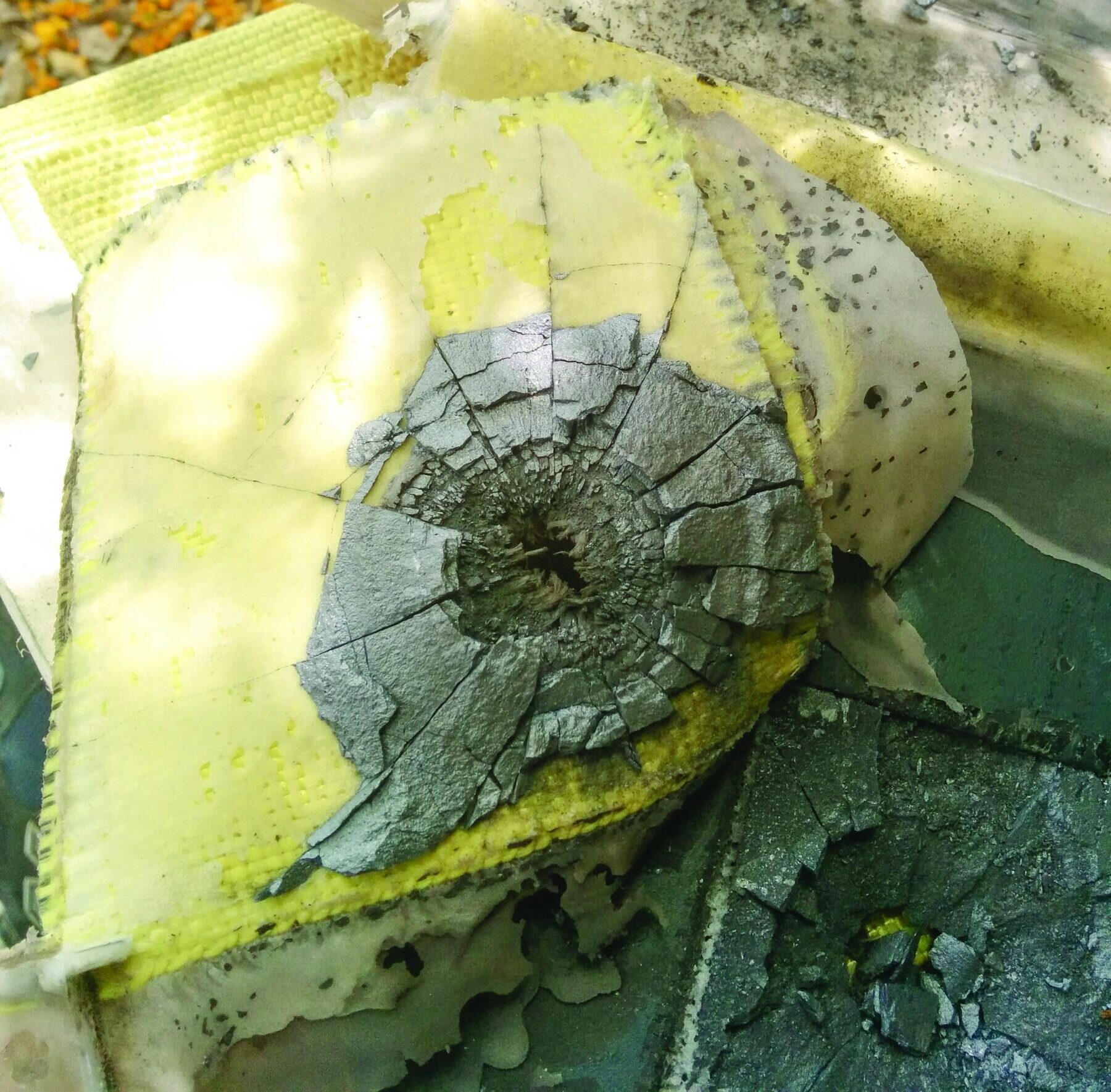

“After we developed new materials and new methods, we shared that with the industry,” he adds. “So it came from the need, and it goes to industry.” (See Figure 1 from Hayun’s article, “Reaction-bonded boron carbide for lightweight armor: The interrelationship between processing, microstructure, and mechanical properties,” ACerS Bulletin, August 2017.)

Figure 1. A BorLite reaction-bonded boron carbide armor plate, manufactured by Paxis Ltd. (Savion, Israel), after impact with 7.62X63 AP M2 projectiles. (Image from ACerS Bulletin, August 2017). Credit: Paxis

ICSI has also been involved in research and development that has its roots in defense requirements, although again, these can ultimately have civilian applications, as well. “We have a few products in the field of ballistic protection, mainly based on boron carbides and a little bit on silicon carbides,” Cohen says. “For optical requirements, there are a few embedded products that we developed and designed. And in the field of piezoelectrics, there are companies that use our design, our formula. So there are quite a lot of products that you can find in security or military applications, and on the civilian side there are also some.”

3-D printing pioneers

Although additive manufacturing only captured popular attention relatively recently, 3-D printing has a history in Israel that dates to 1985, which saw the birth of one of the pioneers in the field, a company called Cubital.

Haim Levi was a member of one of the first Israeli teams to develop a 3-D printing system (Figure 2). Today, he is vice president responsible for the manufacturing and defense industries at XJet (10 Oppenheimer St. Science Park, Rehovot 7670110, Israel), which developed a proprietary technology for ceramic and metal additive manufacturing using liquid materials rather than powders.

Figure 2. XJET Carmel 1400 additive manufacturing system. Credit: Xjet

The company’s founder, Hanan Gothait, is a serial entrepreneur in additive manufacturing whose previous launches include Objet Geometries, which introduced the world’s first polymer jetting technologies and photopolymer 3-D printing systems. It later merged with Stratasys. “So we are here for many years, and we know the technology inside out,” Levi says.

The company, which holds 80 patents, has had a global focus from the outset, in part because the Israeli market is so small, but also because additive manufacturing as an industry tends to think globally. As Levi’s title suggests, Xjet develops solutions that meet defense and manufacturing requirements simultaneously. The technology and materials are the same, although applications “vary quite significantly,” he says. “Nevertheless, we did not develop anything targeted to any specific market.”

As with the technology overall, additive manufacturing for ceramics delivers value in making short runs and eliminates the need for molding or other high-level investments in creating parts. It also removes limitations on geometries. “We can create any geometry that the designer can think of, and in certain cases, we can even make geometries that could not be manufactured with traditional technologies,” Levi says. The end result is increased freedom of design relative to traditional manufacturing techniques.

XJet’s use of liquid rather than powder eliminates the risk of explosion or fire. Its technology also “works in absolutely normal conditions,” Levi says, meaning that there is no need for inert gas, high temperature, pressure, or a vacuum.

The third advantage is high productivity. “We aim at smaller parts with high complexity and highly detailed parts, very accurate parts. Because we work with nanoparticles in very, very thin layers, like 8 microns, it allows us to reach almost fully near net shape result of the production,” he says. “There is very little post-production needed. This is extremely important because machining ceramic parts is pretty tough and can be done only with diamond tools, which is quite expensive and requires a lot of know-how. We are coming very close to the final size and shape of the part in our geometry.”

Another innovation is use of a material for support that “fills out the whole part, internal and external, and thus provides support for the next layer, layer by layer,” Levi says. “By the end of the process, it fills out all the internal voids, cavities, overhangs, and undercuts without being restricted by requirements of support structures. This is a huge benefit, because it means freedom of design. On top of that, there is no need to clean out the supports manually like in other technologies because we dissolve it.”

The company has been using zirconia but intends to expand its portfolio of ceramic materials next year. “We’re definitely looking for sources of raw materials that will go into the liquid,” Levi says. “We are big believers in ceramics in general, and in additive manufacturing within ceramics in particular. We believe there is a big future for that.”

For additional information about Israeli work in additive manufacturing, see the profile of Nano Dimension in the directory.

Technion – Israel Technology Institute in Haifa. Credit: By Orentet – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17506198

Nanotechnology knowledge base

Israel has targeted nanotechnology as a driver of market growth and is committing resources to its economic development. Early-stage Israeli companies abound in the sector. According to the Israel National Nanotechnology Initiative (INNI), whose board is appointed by the Ministry of Economy’s Chief Scientist, Israel has “the third largest concentration of startup companies in the world” in the nanotechnology space, outpaced only by Silicon Valley and Boston’s technology corridor. (See the directory for more information regarding INNI.)

The program at the NANO.IL. 2018 Congress, held October 9–11, at Jerusalem’s International Conference Center, covered a broad spectrum of nano topics, from bionano materials, fabrication, mechanics, and tribology to nanomaterial synthesis and characterization. Sessions were devoted to applications for the defense, nano-electronics, and energy industries, and featured plenary speakers attended from major universities and institutes in the United States and Europe as well as organizations in Israel.

And all is not in a fledgling state in Israel’s nano-universe. In early 2018, Technion (Israel Technology Institute) and the Israel Space Agency announced plans to launch the world’s first nanosatellite formation. The three nanosatellites (each about the size of a shoebox) are to be launched by Innovative Solutions in Space—a Dutch company—and will orbit in controlled formation for one year.

In May, the United Nations International Iberian Nanotechnology Laboratory and Bar-Ilan University’s Institute of Nanotechnology and Advanced Materials (BINA) announced a research and cooperation agreement. And in keeping with its objective of introducing scientific concepts to the general public, BINA is planning the launch of the Joseph Fetter Museum of Nanotechnology. It intends to offer exhibits that make researchers’ work “come to life at the hands of artists, designers, and visionaries.” Guidelines for artworks submitted for consideration may be found online at https://www.drive.google.com/file/d/1l_c19lEMwR8J6mEWUaRmZT_ 4Zv3GK9C/view.

And the Nano-Fabrication center at Ben Gurion University’s Ilse Katz Institute for Nanoscale Science & Technology provides support to the academic, industrial, and governmental sectors. The “R&D and prototype fabrication infrastructure” is suited to “Nano/Microelectronics, BioMEMS, BioChip, Microfluids, Multielectrode array, Nanophotonics and Optoelectronics and Nano/Micro systems (MEMS).”

Not all academic

As these examples illustrate, there can be a strong connection between university-sponsored research, industry, and commercialization of ceramic technology.

Technion sponsors five-day Innovation Workshops that are customized to the needs of the business managers who enroll in each session. The goal is to “promote innovation as a means to enhance sustainable competitive advantage,” the website explains. It uses a process model to walk through problem identification, idea generation, the transformation from idea to product, and market introduction.

The same is true for research institutes like the ICSI, which Cohen describes as doing “research for application”—that is, research with a commercial end in mind. “The commercial, the product, is very important for us. We always take into consideration the economic issues and what will be the price target of the product. We always have it in mind. We do try to commercialize our intellectual property.”

Prof. Hayun of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev says, “The idea of this organization is to develop the technology and the infrastructure in Israel. So they don’t care who is making the money. They care that the technology exists in Israel. And in that way, if there is an Israeli company, then they will support the company to get the knowledge and to market it and sell it.”

At the same time, market limitations can become research limitations. Hayun’s team has for the past five years been researching “the effect of pulse-magnetic oscillation on the solidified structure of casted aluminum.” However, there are no big foundries in Israel. “So our research was published, and if somebody wants to do a startup or a company with that, they will need to go abroad to a country that actually manufactures aluminum. It is an issue. A lot of times, you’re working in fields that you can’t do with the resources that exist in the country. And if the resources are nonexistent, you will go outside.”

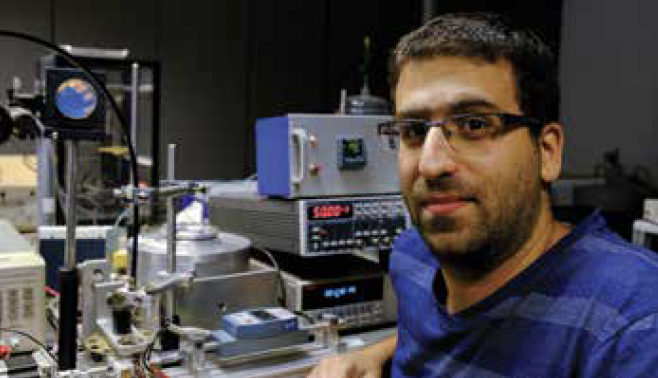

That can create a vicious cycle—but Technion’s Hanna Bishara (Figure 3), a Ph.D. researcher, sees the classroom as part of the solution.

Figure 3. Hanna Bishara, Ph.D. researcher in his laboratory at Israel’s Technion. Credit: Bishara

His research focus is “manipulating crystal growth processes of linear and non-linear dielectrics in order to achieve highlysensitive piezoelectric materials, in the scale of sub-Pascals.” While like any researcher, he would be pleased to be offered research funding by a corporate entity, at this stage of his career, his focus is on research for its own sake rather than on research with commercial potential.

“Whenever we get a solution to some technological problem, we are in a dilemma as to whether to publish it as a scientific report or an article or a paper,” he says. “I want to go more into academia than business, so there’s more worth to Ben Gurion University of Negev, Israel me to publish a paper.”

Some of his colleagues work in a manner more integrated with industry. But Technion also supports that study-centric perspective. “They don’t oblige people to commercialize their research. As a result, you can see a variety of people in Technion, some who do only basic research, and others who are doing a big start-up,” says Bishara.

That opens the door to practical laboratory experience for undergraduates. “For human resources, at Technion, we rely a lot on our bachelor’s students,” Bishara says. “They are integrated into the laboratory in their final year. That’s how I got to my laboratory. I did my final project as an undergraduate, and I liked the research.”

(It is important to remember that these are older students than would be found typically on U.S. campuses because of the requirement that they serve three years in the army before they begin university studies. The average Israeli college student therefore is more mature and has more work experience.)

The Porter School of Environmental Studies Building, Tel Aviv. Credit: Elena Rostunova / Shutterstock.com

Hayun also sees the current generation of students as an important asset in advancing Israel’s knowledge of ceramics and capacity for competing in the global market. “Because of the situation Israel is in, we always need to reinvent ourselves from scratch,” he says. “The students always have new ideas. They give us more and more ideas about how to make ideas work. They know a thing or two about life and what they want to do. This is one reason why you want to collaborate with Israel.”

For now, the country will remain reliant on collaborations with other countries and will have to continue to compete for academic and industry talent on the global market. But by bringing promising members of the next generation into the research realm as early as possible, Israel hopes to cultivate stronger domestic human resources and increased capacity for driving its own growth in ceramic research, product development, and marketing.

Cite this article

A. Talavera and R. B. Hecht, “Israel— Middle East Mavericks,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2018, 97(8): 24–31.

Related Articles

Market Insights

Engineered ceramics support the past, present, and future of aerospace ambitions

Engineered ceramics play key roles in aerospace applications, from structural components to protective coatings that can withstand the high-temperature, reactive environments. Perhaps the earliest success of ceramics in aerospace applications was the use of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) as thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) on nickel-based superalloys for turbine engine applications. These…

Market Insights

Aerospace ceramics: Global markets to 2029

The global market for aerospace ceramics was valued at $5.3 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.0% to reach $8.2 billion by the end of 2029. According to the International Energy Agency, the aviation industry was responsible for 2.5% of…

Market Insights

Innovations in access and technology secure clean water around the world

Food, water, and shelter—the basic necessities of life—are scarce for millions of people around the world. Yet even when these resources are technically obtainable, they may not be available in a format that supports healthy living. Approximately 115 million people worldwide depend on untreated surface water for their daily needs,…