In the highly competitive automotive marketplace, innovation has been a constant since Henry Ford rolled out his first Model T. Yet, automotive glass technology has remained relatively unchanged for almost a century. Today the automotive industry faces increasingly stringent government regulations on fuel economy standards and consumer pull to create a better driving experience while increasing fuel efficiency. The innovation of a thin, lightweight glass-glazing solution can help the automotive industry meet the needs and wants of government and consumers.

The conventional windshield is born

During the early 1900s, motorists drove simple vehicles that lacked protection from road hazards, such as sharp rocks.1 Because of rising safety concerns, automakers introduced the first windshield in 1904. These early models were primitive, made of thick window glass, and considered an added luxury to manufacturers like Ford and Reo that wanted to keep costs down.

In 1915, Oldsmobile offered the first line of vehicles with windshields as a standard piece of equipment. As more motorists entered the roadways and the number of accidents soared, many drivers were quick to blame car manufacturers for injuries caused by flying shards of windshield glass.

As this automotive innovation was taking place in the United States during the early 1900s, European scientist Edouard Benedictus mistakenly discovered laminated glass when he knocked a beaker of dried cellulose nitrate (a form of plastic) to the floor. The glass broke, but its broken pieces stayed together because the plastic coating adhered to the glass when it dried. He recognized that this behavior could have many practical applications. After more experimentation, Benedictus created the first safety glass laminate and pitched the solution to car manufacturers. Benedictus earned a patent for his work in 1909. However, his solution was not put to use until many years later.

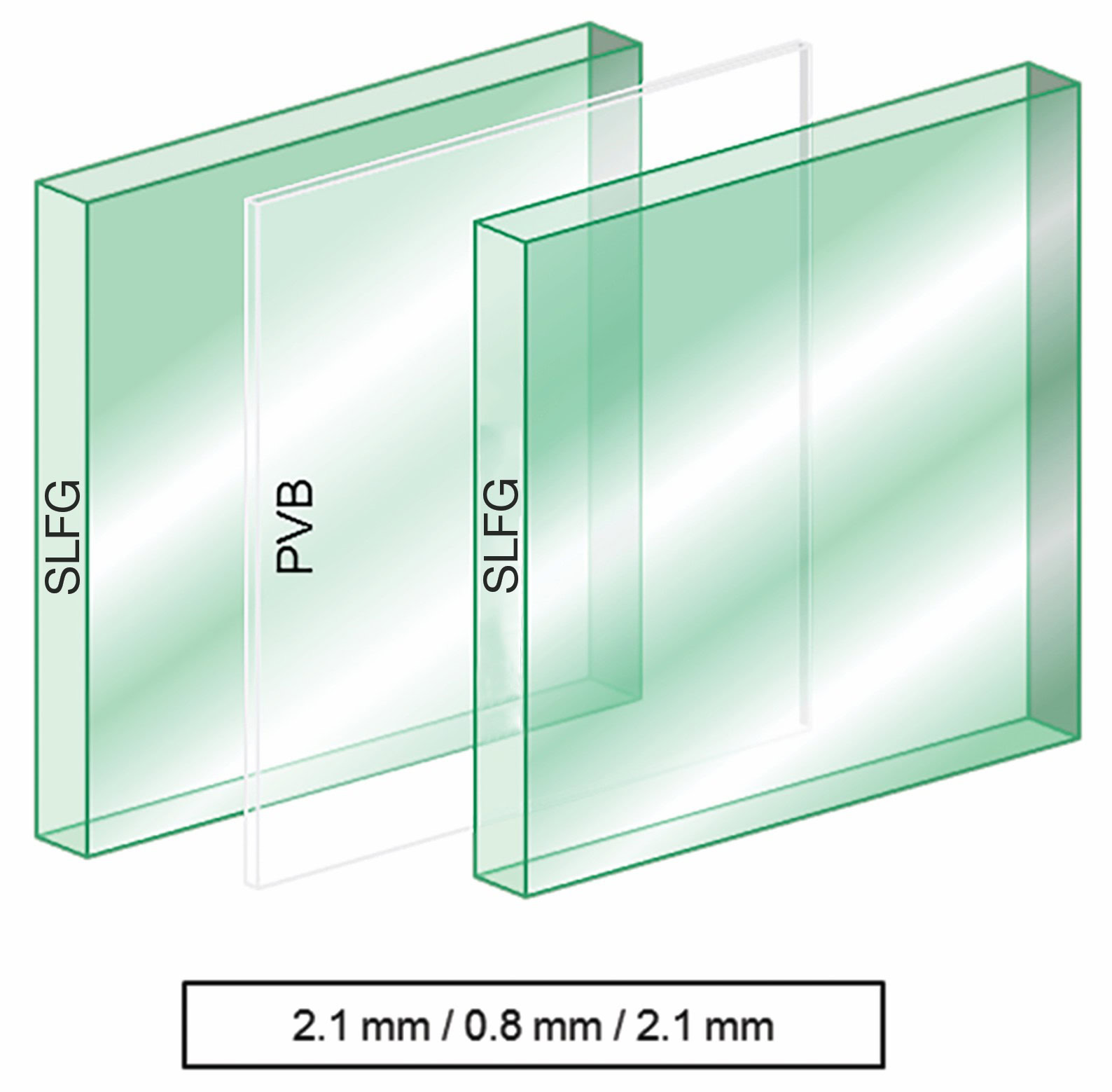

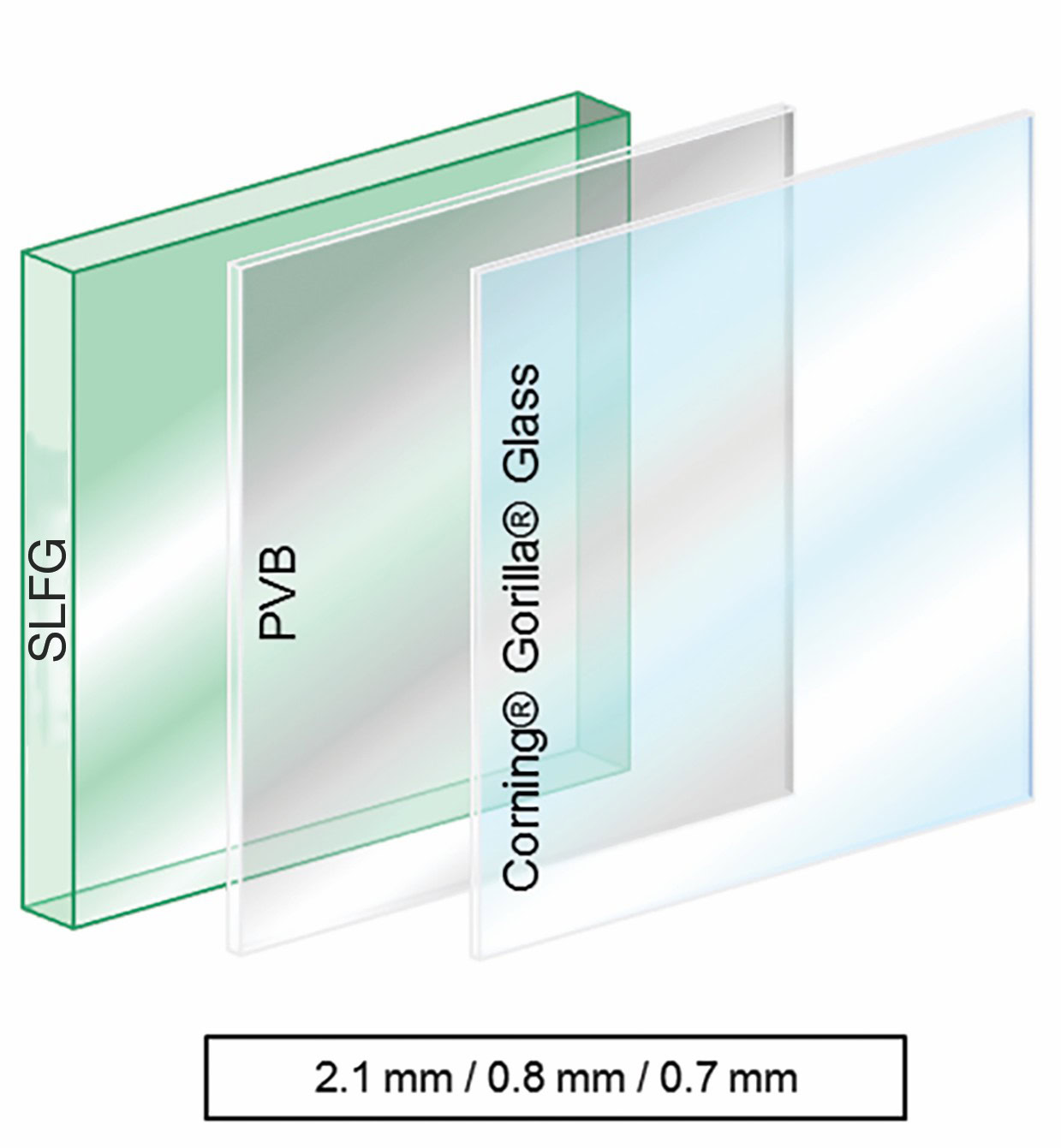

Modern laminate windshields went into practice shortly before 1920, but not much has changed in their fundamental construction since that time. A typical windshield is made from two plies of relatively thick (~2.1 mm) annealed soda-lime float glass (SLFG) bonded together by a layer of poly(vinyl butyral) (PVB) (Figure 1). The PVB layer is ~0.8-mm thick, and its primary purpose is to reduce penetration of objects through the windshield and to retain broken glass in the event of fracture. Although the plastic interlayer in conventional windshields saw considerable innovation between the 1920s and 1960s, the glass has changed little.

Figure 1. Schematic of the construction of a typical windshield, containing two plies of thicker soda-lime float glass bonded together by a layer of PVB. Credit: Corning Incorporated

During the mid-1960s, Corning scientists developed an alternate windshield construction that utilized one ply of Chemcor, a new, chemically strengthened glass.2 The resulting windshield had several desirable attributes, including the ability to survive high strain because of chemical strengthening and its breakage into small cubelike fragments rather than the shards of conventional windshields. Therefore, the new windshield was less prone to lacerate the vehicle’s occupant upon impact during a crash.

However, although Corning’s innovation was impressive, other solutions—such as Pilkington’s revolutionary float glass, which dramatically reduced the cost of sheet glass—also were entering the market. Therefore, Corning decided to shelve the project during the early 1970s.

Need to reduce vehicle weight

The typical passenger vehicle emits ~4.7 metric tons of carbon dioxide every year.3 With more than 1.2 billion cars on the road today worldwide—and the expectation for 2 billion by 2035—regulation of carbon emissions is of utmost importance.4

Government regulations on carbon emissions have become increasingly stringent, bringing the need for lighter vehicles to automotive manufacturers. Manufacturers now are seeking new materials and technologies to reduce vehicle weight to improve fuel efficiency, extend the driving range of electric vehicles, and reduce carbon emissions.

The need to eliminate more and more weight continues to challenge engineers and designers—many have taken unique measures, such as eliminating the vehicle’s spare tire. In the 2015 model year, 36% of vehicles were sold without the customary spare tire, a 5% increase over 2006 models.5

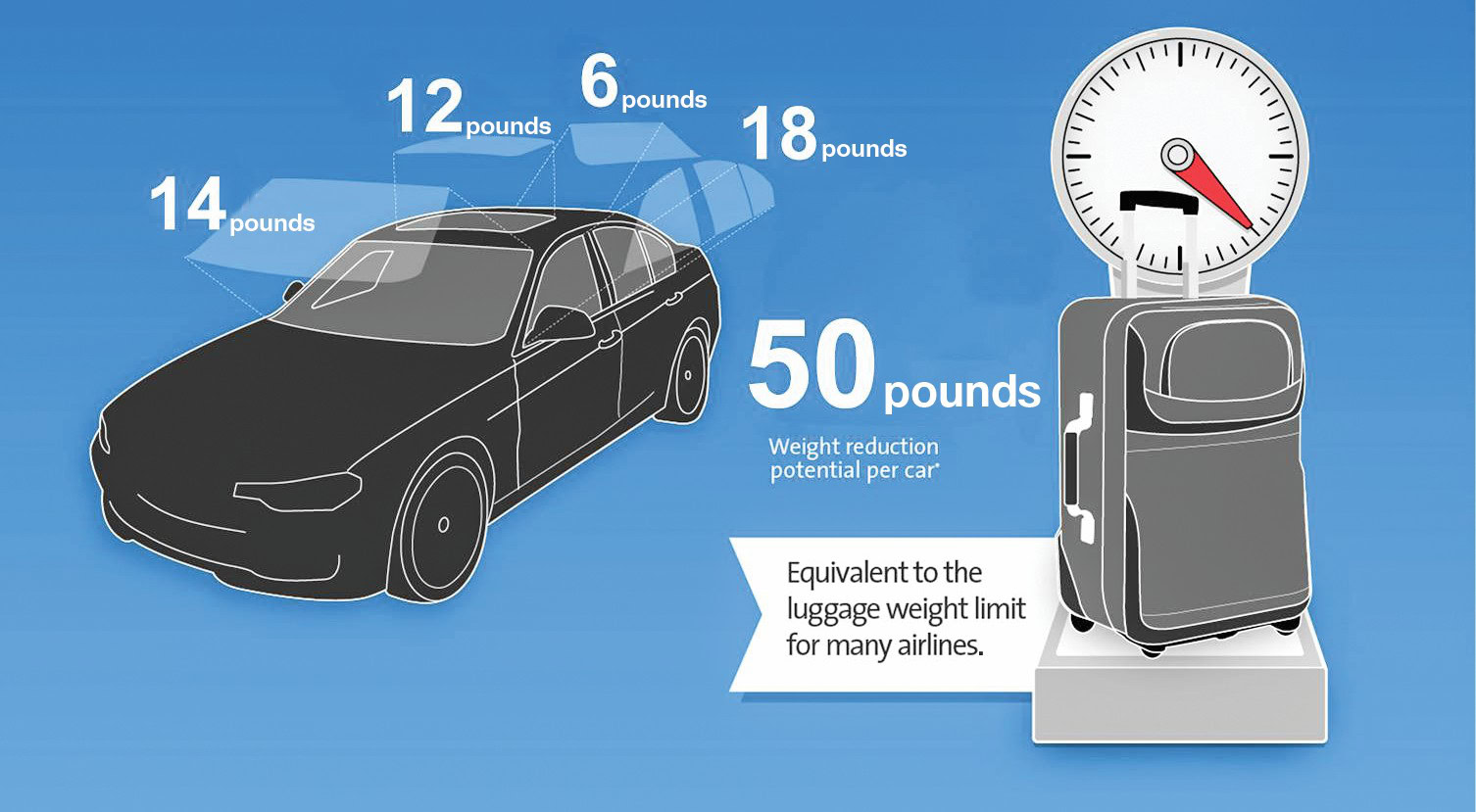

Reduced weight of a vehicle’s glass glazing is a particularly attractive area to help carmakers meet vehicle weight targets. Part of the attraction is that reducing glazing weight lowers the center of gravity of the vehicle because the glazing is located near the top of the vehicle. A lower center of gravity is believed to enable faster vehicle acceleration and braking and may improve handling.

In contrast, eliminating weight from the lower half of the vehicle may have the undesirable result of increasing the vehicle’s center of gravity, which may result in poorer driving performance. Because glazing accounts for most of the top half of the vehicle’s weight, there are not many other opportunities to remove weight from the top portion. Using glazing that is ~30% lighter can reduce vehicle weight by as much as 50 pounds (as calculated by Corning for a sport utility vehicle featuring Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate windows) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Using glass glazing that is ~30% lighter can reduce vehicle weight by as much as 50 pounds, as calculated by Corning for a sport utility vehicle featuring Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate windows. Credit: Corning Incorporated

One attempt from the 1990s to reduce weight used an asymmetrically constructed windshield with a 2.1-mm SLFG outer ply and 1.6-mm SLFG inner ply that was and continues to be deployed primarily in Europe.6 However, little additional progress has been made since that time, and most vehicles in North America continue to use windshields with two plies of SLFG glass that is 2.1 mm or thicker.

Bringing Corning Gorilla Glass to the automotive industry

Most people are familiar with Corning Gorilla Glass as a chemically strengthened cover glass for consumer electronic devices. Since its introduction to the market 10 years ago, Gorilla Glass has been featured on nearly 5 billion consumer electronic devices worldwide.

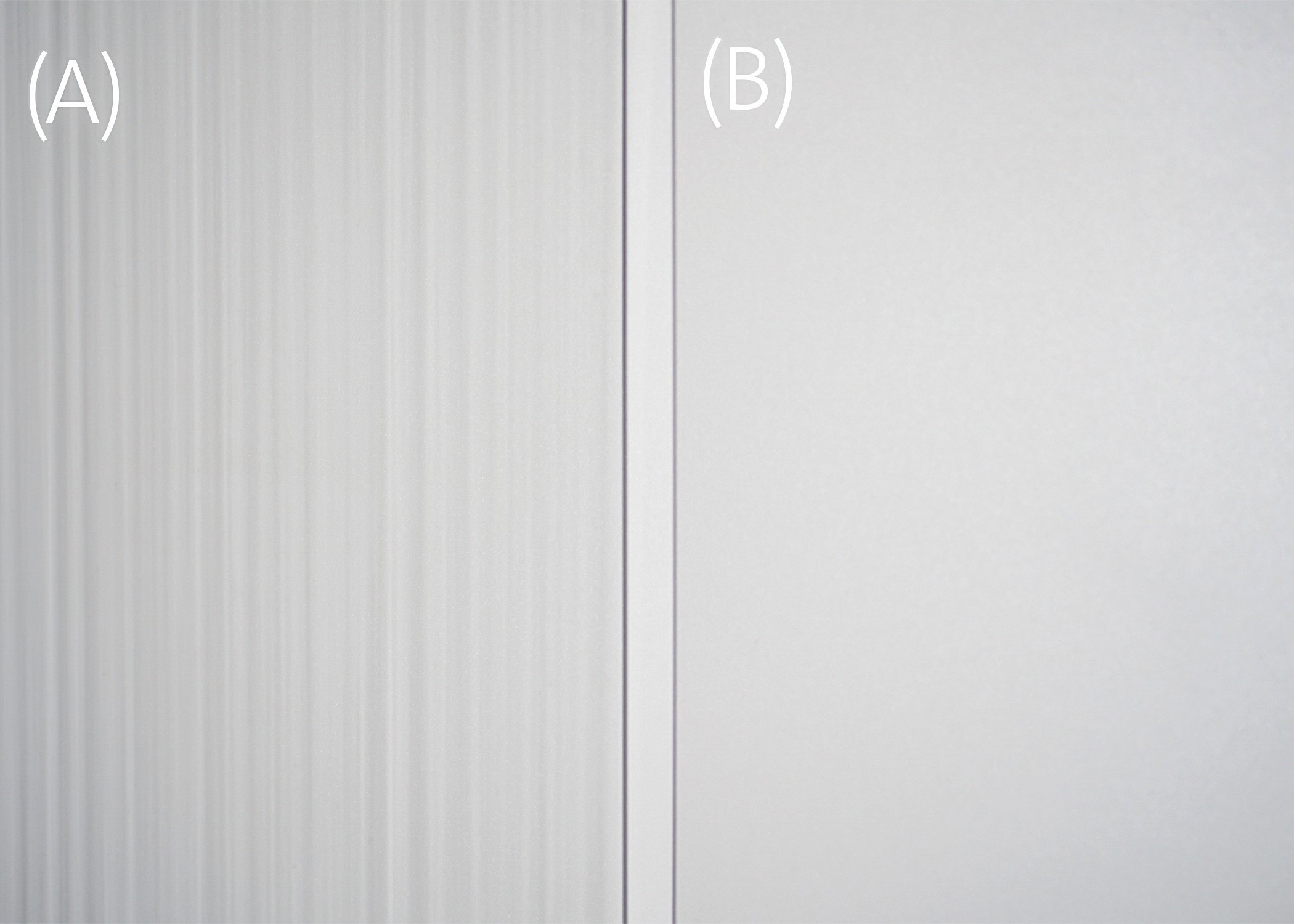

Gorilla Glass is made by Corning’s proprietary glass fusion process, which delivers outstanding optical properties that do not exhibit draw-line distortion typical of float-glass processes (Figure 3). The unique composition of Gorilla Glass also enables a deep level of chemical (ion-exchange) strengthening that typically is not achievable in traditional soda-lime-silica glasses, but which results in a high degree of toughness.

Figure 3. (A) Float glass typically exhibits draw-line distortion, visible here as vertical lines. (B) Fusion-made Gorilla Glass is free of such draw-lines. Credit: Corning Incorporated

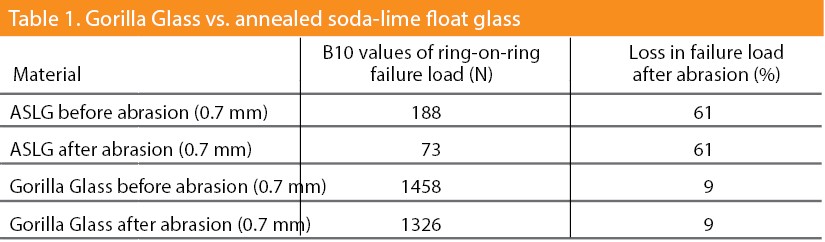

Strength retention testing shows that Gorilla Glass is much stronger in its “as made” condition and retains its strength after introduction of damage, whereas SLFG loses much of its strength after introduction of minor flaws (Table 1).7

*Abrasion done with ISO 12103-I, A4 coarse dust.

Corning sought to take advantage of the toughness of Gorilla Glass to enable lightweight glazing. If glazing could be made thinner and lighter than conventional windows, how could it be engineered to ensure that it could withstand the rigors of the road? Initial glazing applications were addressed on the windshield, because it is the largest window in the vehicle and, therefore, the heaviest and has the most demanding set of requirements.

Lighter solutions for car windshields

Referring back to the conventional car window construction, a standard SLFG windshield laminate has two plies of soda-lime glass—both ~2.1-mm thick—sandwiching a ply of PVB, which is ~0.8-mm thick (Figure 1). Because the density of the two plies of glass is much greater than the single ply of PVB, the only practical way to reduce laminate weight is to address the mass of the glass.

Although Corning evaluated many windshield construction variations, the company determined that a “hybrid” solution incorporating Gorilla Glass and traditional SLFG would deliver optimal performance in most typical applications. This Gorilla Glass hybrid windshield is comprised of a conventional thicker SLFG layer as the outer ply, a typical PVB middle layer, and a thin Gorilla Glass layer as the inner ply.

Exchanging the inner ply of soda-lime glass with a thinner, lighter ply of Gorilla Glass, ranging 0.5–1.0 mm in thickness, can reduce the car windshield’s weight by about one-third (Figure 4). In addition, previous testing has shown that this type of construction complies with North American and European regulatory requirements.8

Figure 4. Schematic of the construction of a Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate with an outer ply of conventional 2.1-mm-thick soda-lime glass, an interlayer of PVB, and a 0.7-mm-thick inner ply of Gorilla Glass. Credit: Corning Incorporated

Superior stone impact resistance

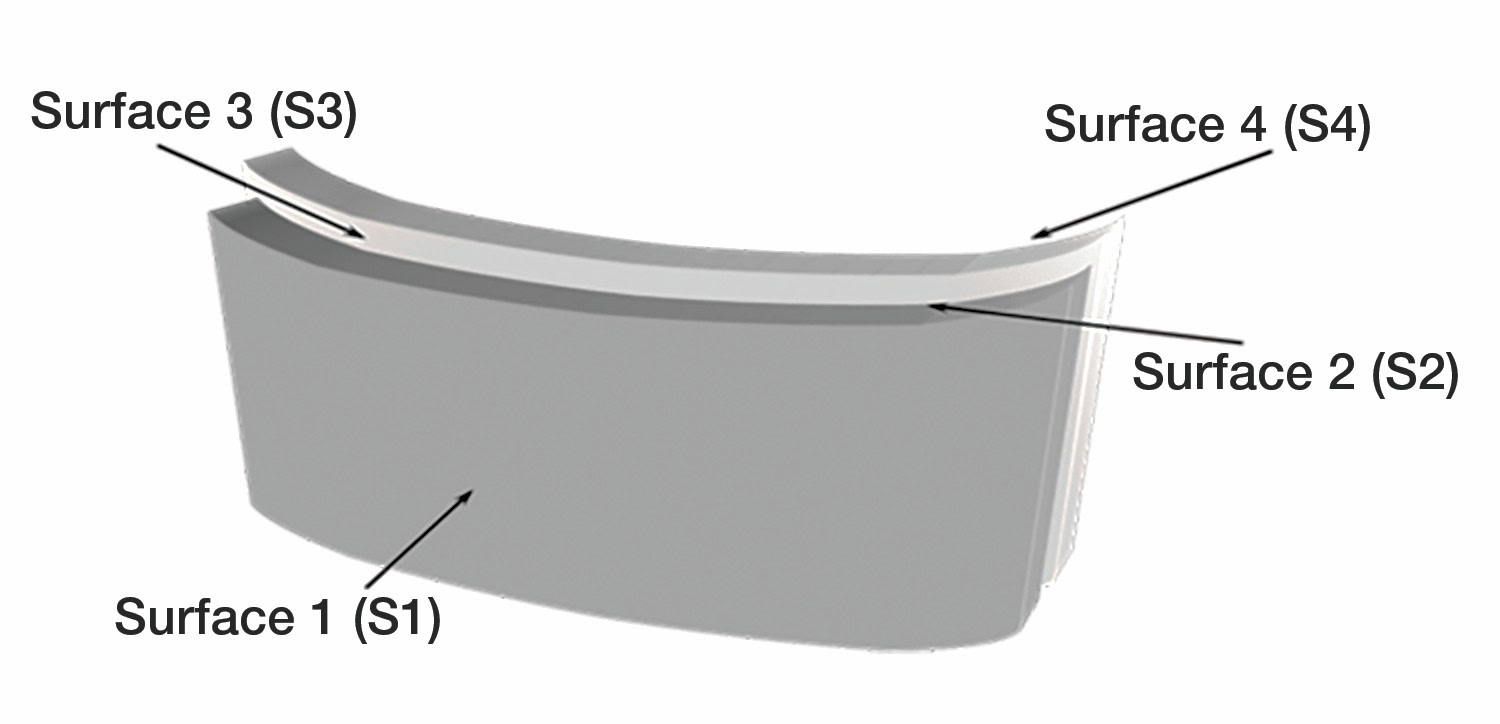

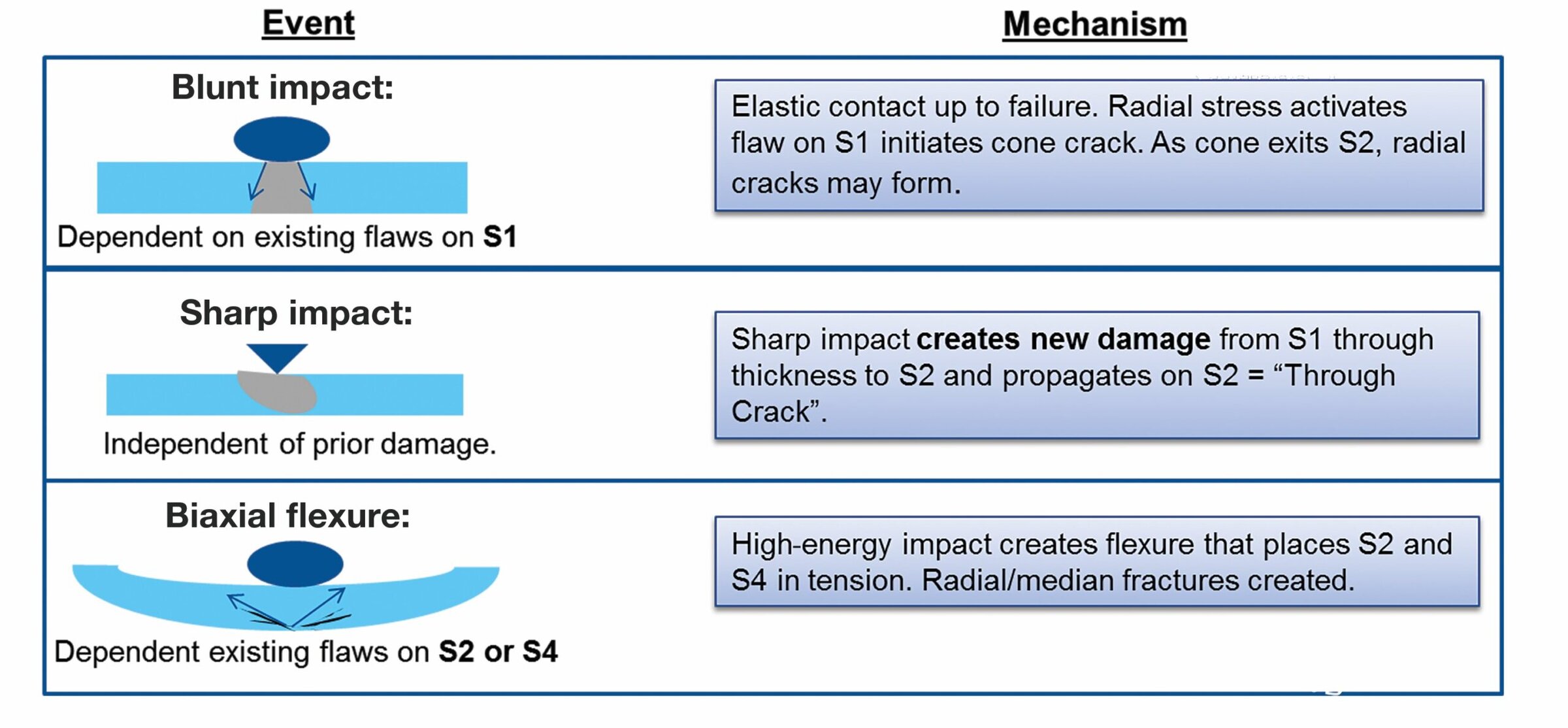

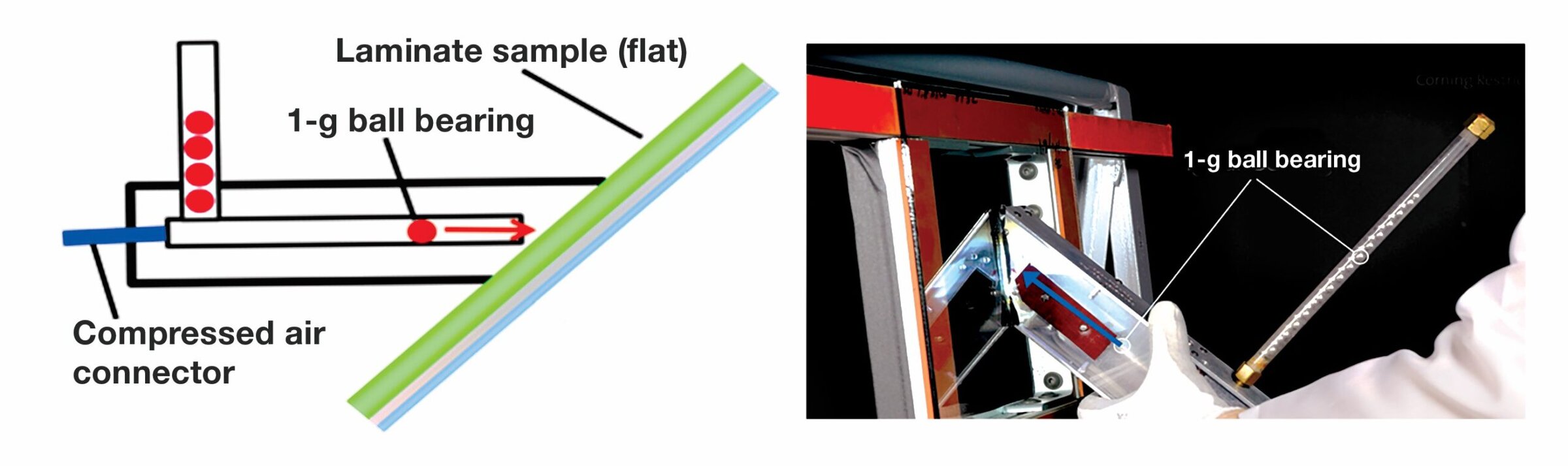

Corning set out to make a lighter windshield, but recognized that the product needed to be able to withstand the typical rigors of use. To understand typical windshield fractures and breakage, Corning scientists performed an in-depth field study and determined that impact events are the largest cause of windshield fractures. These impact events can cause fracture through several different mechanisms and from different surfaces of the laminates (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A windshield consists of various glass surfaces. Credit: Corning Incorporated

- Blunt impact: Hertzian contact stresses create radial stress on the exterior surface (S1) of the windshield and activate an existing flaw. This results in a full or partial ring crack that may grow into a cone crack. Radial cracks often form when the cone crack exits the back side of the outer ply (S2).

- Sharp impact: Contact stresses of a sharp stone create damage, which is driven through the thickness of the outer ply. Once damage crosses beyond the neutral axis of the laminate, damage pops into radial and/or median cracks. Because this type of impact creates its own damage, preexisting flaws do not play a major role in this failure mode.

- Flexure: Upon impact, the laminate flexes away from the impacting object, causing tensile stresses on S2 and S4, which can activate existing flaws on these surfaces and lead to radial or median fractures (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Stone impact is the greatest cause of windowscreen replacements. The three primary mechanisms of fracture are impact events. Credit: Corning Incorporated

Tests replicating each impact scenario on conventional and Gorilla Glass hybrid laminates revealed some surprising results.

Figure 7. Small particle, blunt impact testing setup. Credit: Corning Incorporated

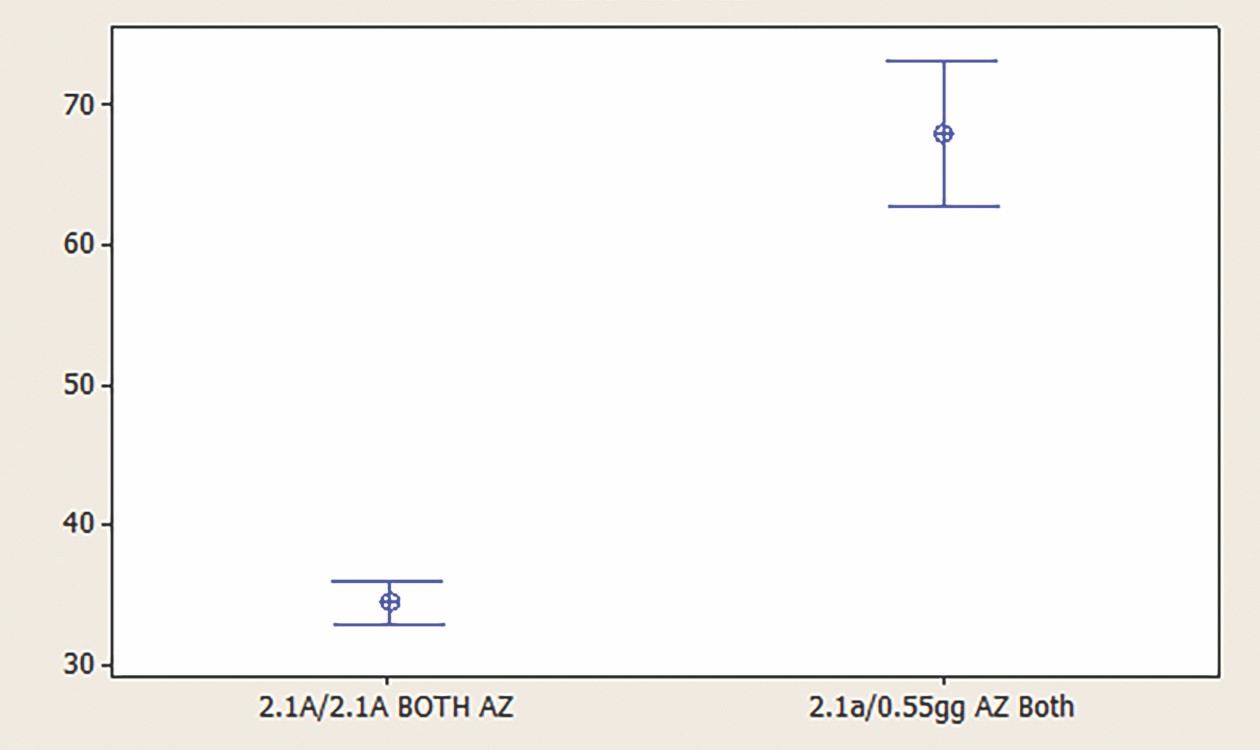

- Blunt (Hertzian) contact: Because failure is dependent on preexisting flaws, parts were preabraded7 and Hertzian contact stress was applied on the windshield using a 1-g stainless-steel ball bearing at a 45° angle of incidence (Figure 7). Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate outperformed conventional laminate (Figure 8). In addition, laminates that incorporate thin nonstrengthened glass often result in inner ply breakage because of the flexure mechanism of glass upon impact.7

Figure 8. Interval plot of break velocity results for 1-g ball-bearing impact testing at 45° incidence for abraded S1 and S4 (95% confidence interval for the mean). Left data point is conventional laminate; right data point is hybrid Gorilla Glass laminate. Credit: Corning Incorporated

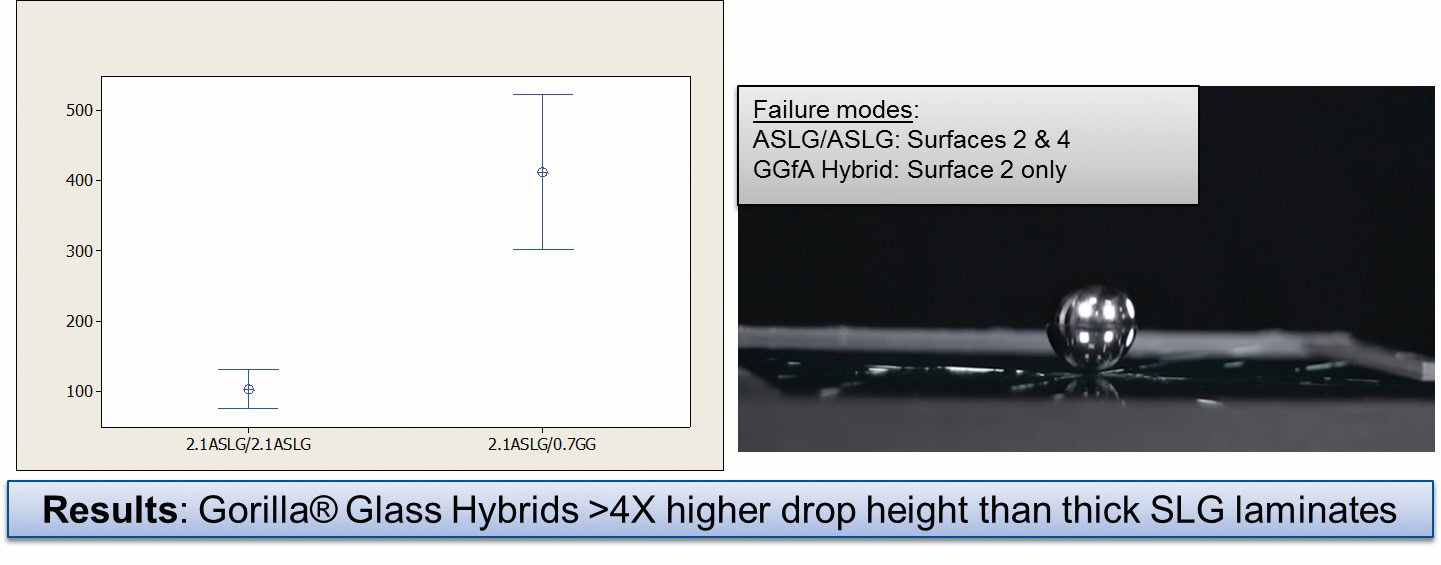

- Large blunt impact: A stair-step drop test using a 227-g ball simulated impact events, such as hail or a baseball hitting a windshield. Because failure of this impact is caused by flexure of the backside of the laminate, parts were preabraded to equally damage each sample set. Gorilla Glass hybrid laminates withstood more than four times the drop height of conventional laminates before sustaining breakage (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Interval plot of drop height results for 227-g ball drop testing for abraded S4 (95% confidence interval for the mean). Left data point is conventional laminate; right data point is hybrid Gorilla Glass laminate. Credit: Corning Incorporated

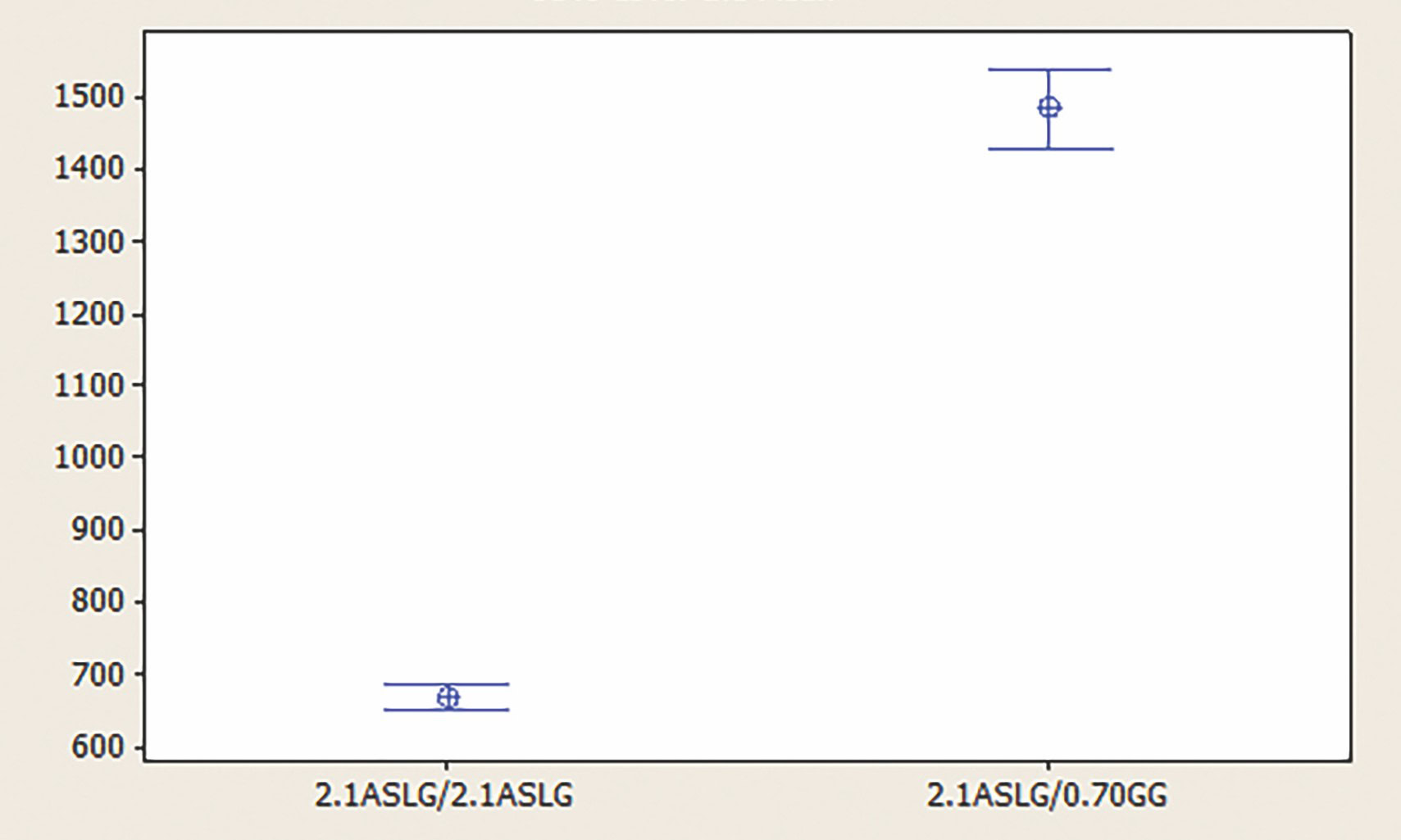

- Sharp impact: This test is perhaps most significant, because sharp impact is the most prevalent cause of windshield failure in the field. Dropping an 8.5-g pyramid-shaped (Vickers) diamond indenter onto S1 (exterior surface) tested sharp impact. In this case, surfaces were not preabraded, because this type of event does not depend on pre-existing flaws. Gorilla Glass hybrid laminates required more than two times the energy of conventional laminates to create radial cracks in the glass (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Interval plot of drop-height results from sharp-impact (Vickers) diamond testing (95% confidence interval for the mean). Credit: Corning Incorporated

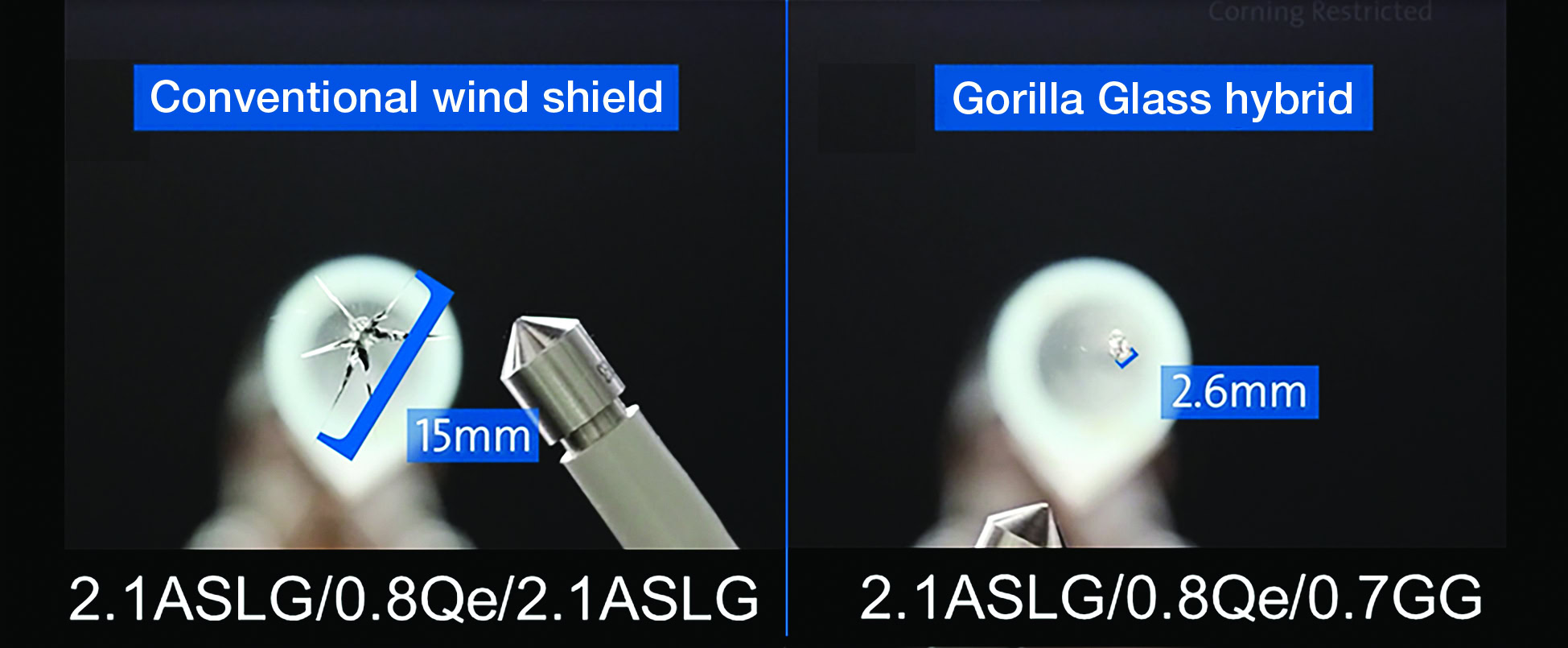

Figure 11 shows the damage resulting from sharp impact of laminate constructions at 1,200 mm. The conventional laminate construction developed multiple radial cracks extending up to 15 mm in length, whereas the Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate exhibited only a small chip in the surface.

Figure 11. Photographs of postimpact damage of conventional laminate and Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate with Vickers diamond at 1,200 mm. Credit: Corning Incorporated

These results are important, because radial cracks are strength limiting and significantly more prone to propagation than minor chips in glass. We demonstrated this with a thermal shock test that simulates washing a car on a hot day, when windshield glass will be very hot and water will be cold. Radial cracks quickly propagate across conventional windshields, whereas Gorilla Glass hybrid windshields with only small surface chips are stable and do not propagate in this test.

How does this ‘toughness’ work?

The data indicate that thin Gorilla Glass hybrid laminates should be more resistant to sharp-stone impacts during service. The following equation, which describes the energy balance of impact, helps illustrate why:9

KE = Es + Ef + Er

where KE represents kinetic energy of impact, Es energy of bending, Ef energy for fracture, and Er energy for rebound.

The improved performance of Gorilla Glass hybrids likely is driven by the additional flexure provided by this thin laminate upon impact (rigidity is a function of thickness cubed, thus thinner laminates have a much greater Es). Because a larger component of the energy of impact is dissipated by flexure of the glass or laminate, there is less energy available to develop contact stresses at the surface of the part that eventually lead to radial or cone crack formation.

However, because of lower laminate rigidity, stresses experienced on the back side of the laminate (S4) will be much higher. Toughness of Gorilla Glass (especially when used as the inner ply to form the back side) allows the laminate to survive these higher stresses because of flexure. Accordingly, Gorilla Glass hybrid laminates take advantage of a combination of flexure and toughness to exhibit improved sharp and blunt impact performance.

Optical advantages of Gorilla Glass

Corning’s proprietary fusion draw process results in glass that is free of significant draw-lines (Figure 3). Therefore, when light traverses through the glass, there is little apparent distortion or imperfection of objects to the viewer, as is typical of thinner SLFG. The two combined plies of SLFG in traditional automotive laminates can amplify this distortion because of overlap of draw-lines. Therefore, Gorilla Glass hybrid laminates mitigate this risk of deleterious overlap by incorporating only one ply of float glass.

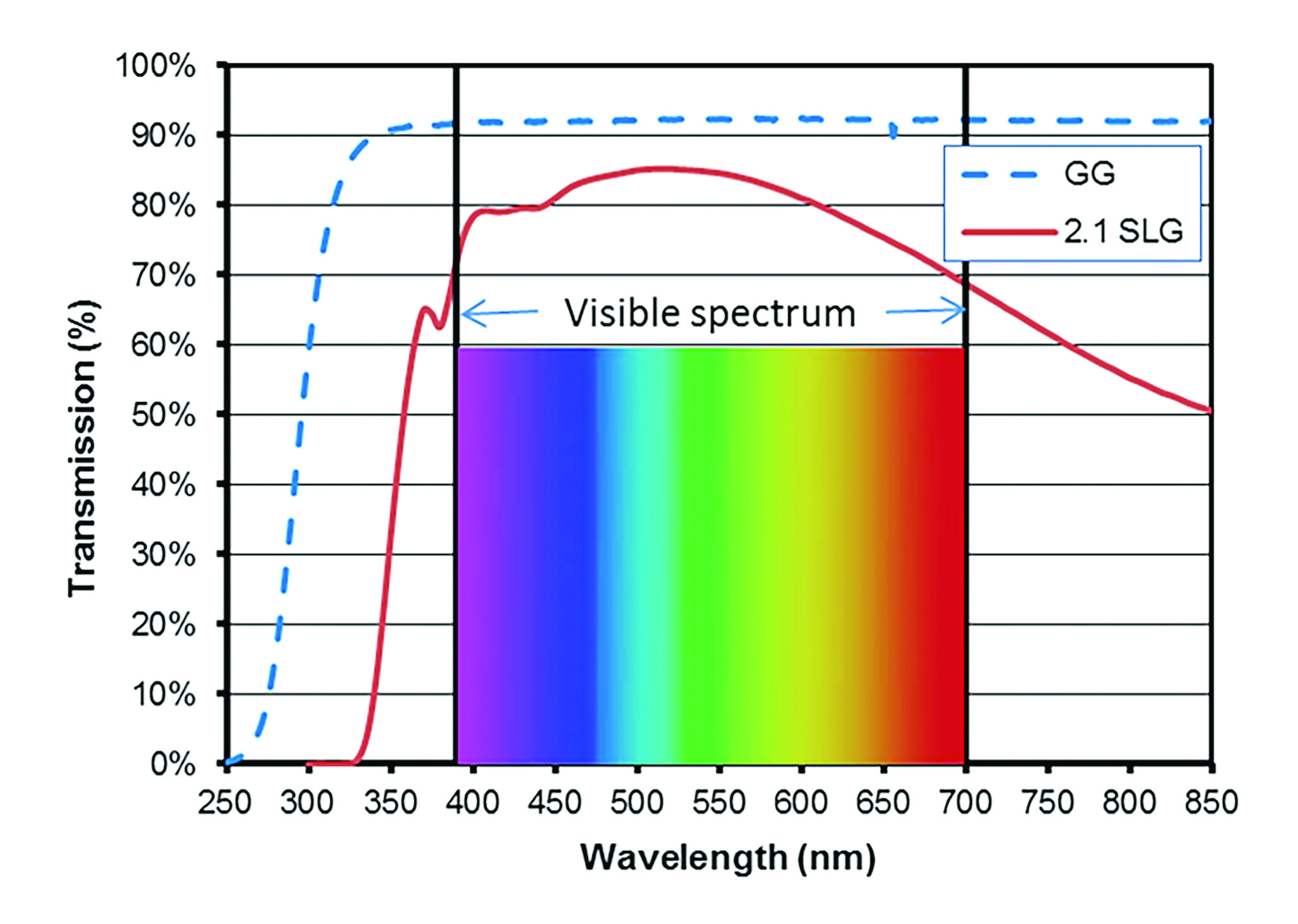

In addition, two combined plies of SLFG add to cross-car distortion, which may create an uncomfortable driving experience. Because Gorilla Glass is very thin and free of significant draw-lines, it does not significantly distort light transmission through the glass. Also, scenery viewed through Gorilla Glass hybrid laminates is more color-neutral, because Gorilla Glass has a flatter transmission spectrum than soda-lime glass (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Transmission spectrum of typical soda-lime glass and Gorilla Glass (GG). Credit: Corning Incorporated

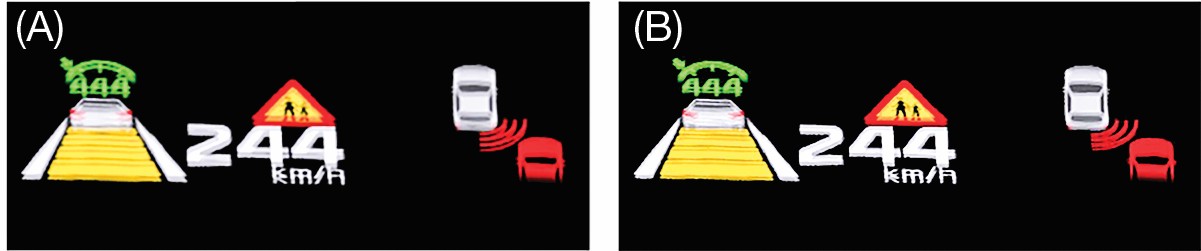

The Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate has another benefit for deployment of head-up display (HUD) technologies. In a conventional HUD unit, projection of an image and its transmission through thick laminate glass can cause image separation, or ghosting. This image ghosting can be uncomfortable for drivers’ eyes, prompting them to disable the HUD unit entirely.

One solution to reduce HUD ghosting is implementing a wedge angle in the PVB layer to minimize the image offset. However, wedge angles are optimized for a driver of a nominal height—so shorter or taller drivers still experience image ghosting, which can be even worse.

A thinner glazing solution provides more margin for the overall optical system, making it less prone to variations from nominal design. This can help reduce ghosting that may occur for drivers of all heights (Figure 13). The thinness of the Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate reduces image separation and provides a clearer HUD image. Its flatter transmission spectrum also can contribute to better image quality and color rendering for HUD images.

Figure 13. Simulated ghost images for (A) conventional 5.0-mm silica-lime glass windshield and (B) 3.6-mm Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate for a tall driver. Credit: Corning Incorporated

For drivers at night, bright light shining into the cabin of the car, such as a street light or headlights from oncoming traffic, also can cause transmission ghosting. This ghosting worsens with thicker glass and the addition of wedge angles to reduce HUD ghosting. However, the Gorilla Glass hybrid laminate can reduce transmission ghosting because of its thinness and lower wedge angle, improving night vision without relying on complex PVB designs.

Additional benefits of lightweight glazing

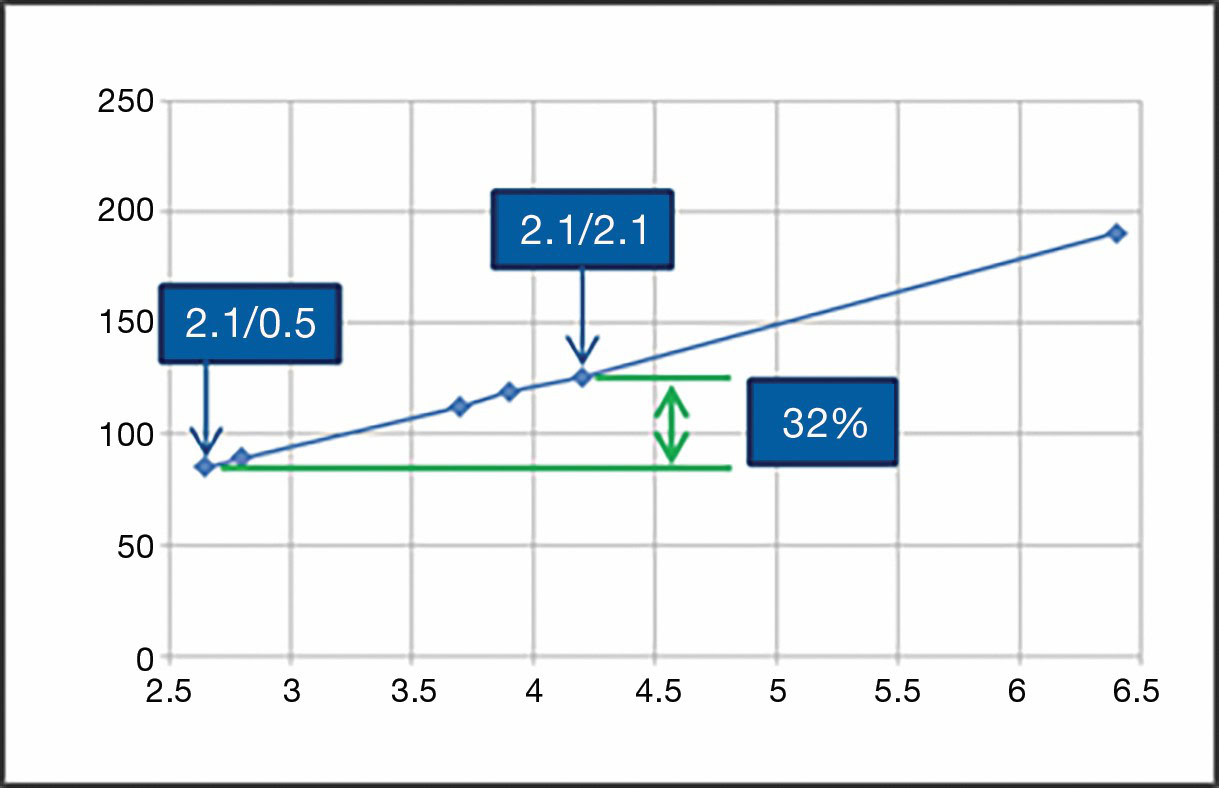

The significantly lower mass of Gorilla Glass hybrid laminates also allows them to defog and defrost 30% faster than traditional conventional windshields. This should decrease idle time for the vehicle and driver and reduce time wasted scraping ice off windshields and windows (Figure 14). These savings are particularly relevant for fleet operators who lose valuable driving time while waiting for defrosting.

Figure 14. Defrost time as a function of laminate thickness. Credit: Corning Incorporated

A lightweight future

Today, government regulations have become increasingly stringent with fuel economy standards, and consumers want to get more out of vehicles without causing additional harm to the environment. To meet these regulations, automakers continue to look for new ways to reduce weight of their vehicles. Corning’s Gorilla Glass—a thin, lightweight, and optically clear glass—can help solve this problem. This exciting new innovation for automobiles can help automakers meet specifications and regulations while ultimately helping consumers enjoy a better ride.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Emily Steves and Kimberly Keorasmey for their assistance in the preparation of this document. Additionally, the authors thank Sang-Ki Park and Ah-Young Park for their insights.

Capsule summary

Unchanged innovation

Although the conventional glass windshield laminate was developed almost a century ago, very few changes have been made since then to the laminate’s construction.

Changing times

Increasingly stringent fuel economy standards and performance demands are requiring automakers to look for new ways to reduce vehicle weight, and glass is a clear target.

Going Gorilla

Corning Incorporated has brought Corning® Gorilla® Glass to the automotive space, where it can reduce vehicle weight and enable increased fuel economy, improved durability, and an enhance driving performance.

Cite this article

T. Cleary, T. Huten, V. Bhatia, Y. Qaroush, and M. McFarland, “Lighter, tougher, and optically advantaged: How an innovative combination of materials can enable better car windows today,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2017, 96(4): 20–27.

About the Author(s)

All authors are affiliated with Corning Incorporated (Corning, N.Y.). Contact Thomas Cleary and ClearyTM@corning.com.

Issue

Category

- Glass and optical materials

- Manufacturing

Article References

1L. Hedgbeth, “A clear view: History of automotive safety glass,” 2017, http://www.secondchancegarage.com/public/windshield-history.cfm;%20http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Automobile-Windshield.html;%20http://www.autoglassuniversity.com/mod01/mod01.php;%20http://www.hg.org/article.asp?id=19112.

2M.B.W. Graham and A.T. Shuldiner, “The market that wasn’t there: The safety windshield”; pp. 264–67 in Corning and the Craft of Innovation. Oxford University Press, New York, 2001.

3“Greenhouse gas emissions from a typical passenger vehicle,” 2016, https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/greenhouse-gas-emissions-typical-passenger-vehicle-0

4J. Voelcker, “1.2 billion vehicles on world’s roads now, 2 billion by 2035: Report,” 2014, http://www.greencarreports.com/news/1093560_1-2-billion-vehicles-on-worlds-roads-now-2-billion-by-2035-report

5J. Crucchiola, “Automakers are sacrificing the spare tire for fuel economy,” 2015. https://www.wired.com/2015/11/automakers-are-sacrificing-the-spare-tire-for-fuel-economy/

6D. Linhofer and M. Maurer, “Lightweight conventional automotive glazing”; presented at International Body Engineering Conference (IBEC) (Sept. 30–Oct. 2, 1997, Stuttgart, Germany).

7T. Cleary, T. Huten, D. Strong, and C. Walawender, “Reliability evaluation of thin, lightweight laminates for windshield applications”; presented at Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) (April 5, 2016, USA).

8T. Leonhard, T. Cleary, M. Moore, S. Seyler, and W.K. Fisher, “Novel lightweight laminate concept with ulrathin chemically strengthened glass for automotive windshields,” SAE Intl. J. Passeng. Cars-Mech Syst., 8 [1] 95–103 (2015), doi: 10,4271/2015-01-1376.

9D. Dürkop and R. Weißmann, “Investigation of the mechanism of stone impact on laminated glass windscreens”; presented at XV International Congress on Glass, Leningrad, 1989 (July 2–7, 1989, Leningrad, Russia).

Related Articles

Market Insights

Engineered ceramics support the past, present, and future of aerospace ambitions

Engineered ceramics play key roles in aerospace applications, from structural components to protective coatings that can withstand the high-temperature, reactive environments. Perhaps the earliest success of ceramics in aerospace applications was the use of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) as thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) on nickel-based superalloys for turbine engine applications. These…

Market Insights

Aerospace ceramics: Global markets to 2029

The global market for aerospace ceramics was valued at $5.3 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.0% to reach $8.2 billion by the end of 2029. According to the International Energy Agency, the aviation industry was responsible for 2.5% of…

Market Insights

Innovations in access and technology secure clean water around the world

Food, water, and shelter—the basic necessities of life—are scarce for millions of people around the world. Yet even when these resources are technically obtainable, they may not be available in a format that supports healthy living. Approximately 115 million people worldwide depend on untreated surface water for their daily needs,…