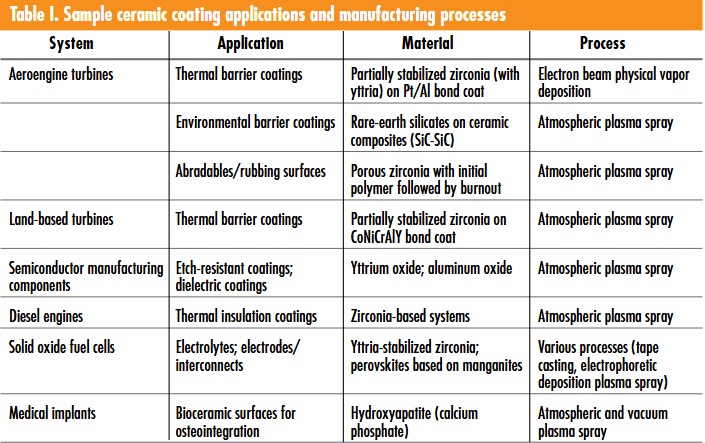

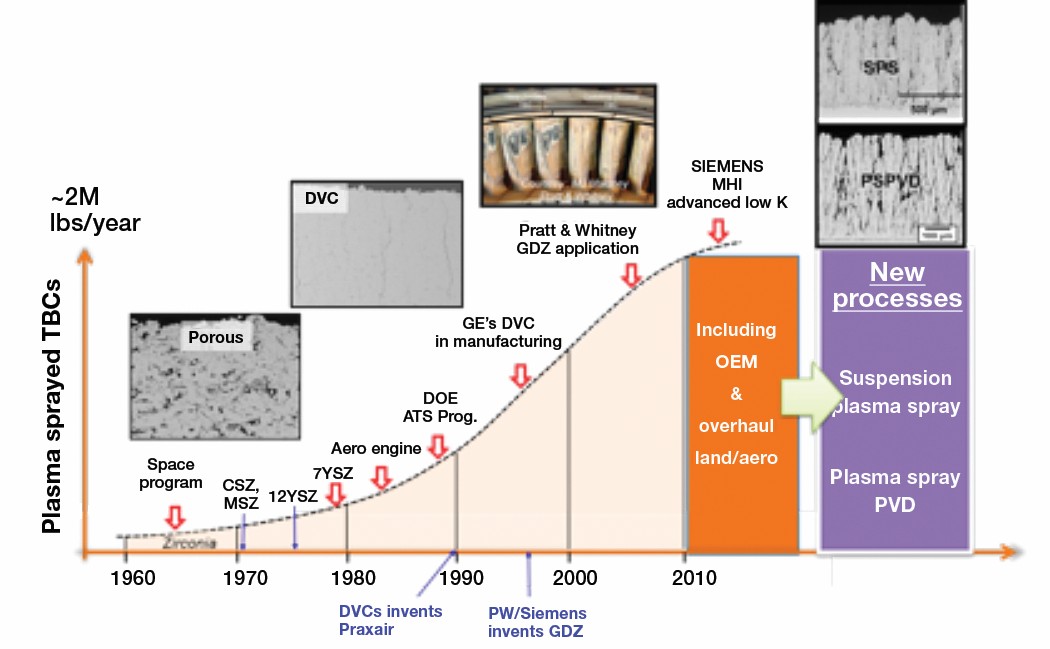

We apply ceramic coatings to substrates for a variety of reasons, including for protection, to improve durability, and to add functionality. Thin- or thick-film coatings provide thermal, corrosion, and wear protection and impart frictional, conductive, dielectric, magnetic, and sensory attributes (Table I). As an exemplar, thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) and environmental barrier coatings (EBCs) are pervasive in engineering components (Figure 1). In addition, coatings are growing in importance as functional surfaces.

The Interagency Coordinating Committee for Ceramic Research and Development (ICCCRD) is composed of representatives from government agencies with programs on ceramics.1 ICCCRD hosts regular workshops on selected topics of interest. Previous ICCCRD workshops, in which additional scientists also were invited to attend, focused on materials databases,2 scarce materials,3 ceramic education,4 and computation and modeling.5 The most recent ICCCRD workshop, which took place in March 2016, focused on ceramic coatings and films, emphasizing TBCs and EBCs for engine applications and thermal protection systems used in reentry vehicles.

Although we recognize that ceramic thick films and coatings also find varied applications in electronic multilayers, fuel cells, batteries, thermoelectrics, and sensors, we devote little space to these topics herein. Instead, we maintain the focus of the ICCCRD workshop.

Figure 1. Schematic of a thermal barrier coating (center), along with images of a coated stator vane (left) and an annular combustor covered in coating tiles (right). Credit: Siemens Energy

History of films and coatings

In a recent publication, Greene6 traces the history of film technology during the 5,000 years until the early 1900s. Although he devotes most of the paper, particularly the early part, to metal films, he provides a remarkable perspective on the development of various deposition procedures.

As early as the mid-1760s, researchers used cathodic-arc deposition to grow metal oxide films. With the advent of sol–gel processing in the mid- to late-1800s, interest in ceramic and glass coatings grew—first with silica, followed by silazanes (hydrides of silicon and nitrogen) and vanadium pentoxide, and then other oxides. Around the same timeframe, sputter deposition and plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition emerged.

Greene discusses the use of CaF2 films deposited by thermal evaporation to produce antireflective coatings. He points out that reactive evaporation of metal oxides for optical films, such as TiO2, was developed in the 1950s. Today, we extensively use ceramic films for myriad applications. Herein, we focus mostly on two historical aspects of coating technology—TBCs and EBCs.

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), a predecessor to NASA, sponsored an early study on the use of ceramic coatings applied to turbine engine components in an effort to operate them at higher temperatures. NACA published a report on the study in 1947.7 This study, begun in 1942 at the National Bureau of Standards, the predecessor to NIST, involved use of alumina-containing frits that were sprayed onto metal alloys and then fired. Thermally treating the coated parts at elevated temperatures had varying degrees of success. Some of these frits later were tested on actual turbine blades.8 Early studies (ca. 1960) also involved the use of flame-sprayed coatings for rocket applications,9,10 specifically zirconia-based coatings used in X15 rocket nozzles.

Pratt and Whitney conducted some of the first efforts to use TBCs for commercial aircraft applications beginning in the early-1970s. Miller9 reports that plasma-sprayed TBCs were used in commercial conductors at about this time. NASA Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, did considerable early work on TBCs.11 Researchers there in 1976 successfully applied plasma-sprayed Y2O3-stabilized ZrO2 coatings to a variety of nickel-based superalloys containing an aluminum-rich, nickel-based bond coating. Testing these structures for up to one hour in a burner rig at temperatures up 1,540°C resulted in some degradation, although the coatings did reduce surface temperature by up to 190°C with no observed gross spalling.

Ceramic coatings of today

Modern coatings comprise a large array of materials and range in thickness from one monolayer to thick films. Manufacturers produce them through various methods, from vapor deposition to spray deposition, and the coatings include a vast array of materials. Areas of focus and interest include new materials, tunability of microstructure and properties, growth of artificial materials (such as superlattices) and metastable phases, and strain engineering. Slightly more than half of the awards in the Ceramics Program at the National Science Foundation (NSF) deal with coatings, layers, or films (based on the grant title and/or abstract). A similar percentage includes surfaces, interfaces, or nano-wires, with a tremendous richness in the variety of materials.

There are important applications that rely on functional properties and a material’s hardness, toughness, and wear resistance. These include dielectric coatings—such as SiO2, AlN, and Si3N4—used in microelectronics, and hard coatings—such as SiC, TiN, TiB2, and Al2O3—for wear and corrosion protection. According to Glen Mandigo, executive director of the United States Advanced Ceramic Association (USACA), a speaker at the workshop, coating opportunities exist for fibers and nuclear fuels as well as monolithic ceramics and ceramic-matrix composites (CMCs). One interesting application is high-conductivity, antireflective coatings for optical windows. However, at NASA and Department of Defense agencies, a smaller subset of materials—especially TBCs, EBCs, and ultra-high-temperature coatings—garner interest.

Current issues for TBCs

Several presenters at the ICCCRD workshop focused on use of high-temperature TBCs and EBCs in turbine engines. Representatives from the Office of Naval Research (Steven Fishman), NASA Glenn Research Center (Dongming Zhu), and the Center for Thermal Spray Research at Stony Brook University (Sanjay Sampath) presented various aspects of ongoing research and development on such coatings.

Commercial and military aircraft as well as land-based engines representing 20% of the world’s generation of electricity extensively use turbine engines.12 A recent publication provides an excellent compilation of articles on current TBC research and technology.13

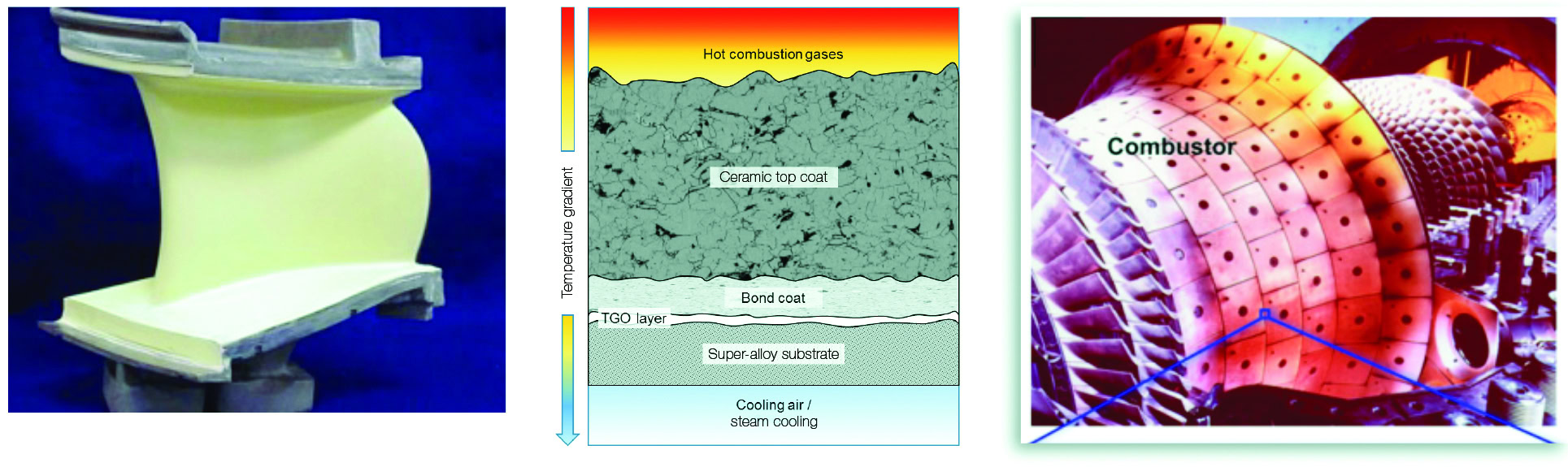

Figure 2. Growth of the application of thermal barrier coatings via plasma spray (in pounds per year of powder consumption) since its evolution as well as key current and emerging microstructure, materials, and process variants.15 Credit: Sanjay Sampath

At the workshop, Sampath pointed out the extensive use of TBCs in engines and showed the evolution of materials during many years (Figure 2). He illustrated the point that coatings are pervasive in gas turbine engines, where they are used for thermal protection as well as wear and corrosion resistance. He emphasized that a goal of developing improved coatings is to make them “prime reliant,” i.e., their performance is essential to operation of the engine. Sampath showed how improved thermal spray manufacturing, coupled with a better understanding of microstructure development, has led to significantly improved properties, such as fracture toughness, to lead to durable and reliable performance.14

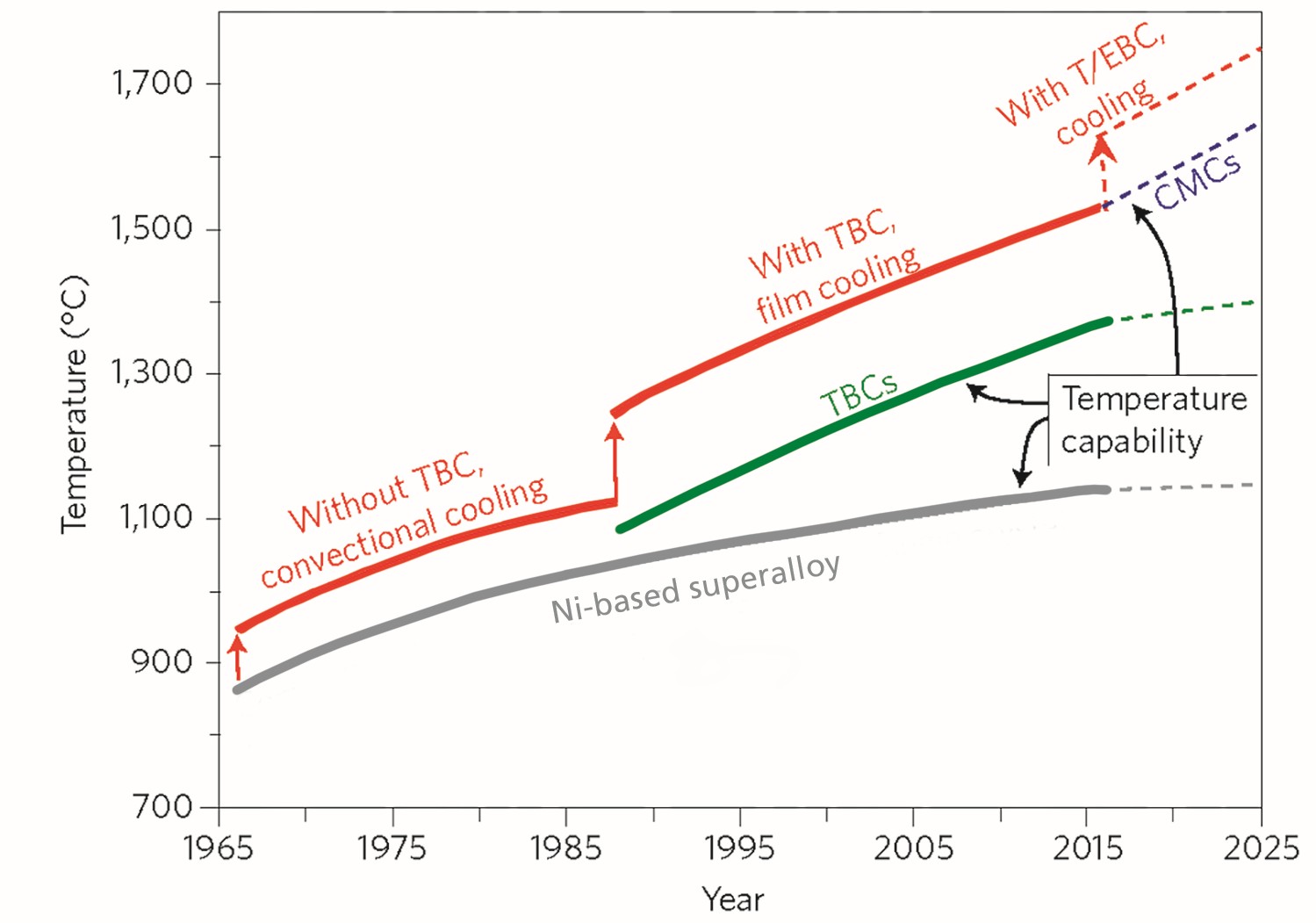

Figure 3. Historical trends in engine operating temperatures, showing temperature capabilities of various gas-turbine engine materials, including Ni-based superalloys (grey), TBCs (green, estimated), and CMCs (blue, estimated). Red lines indicate estimated maximum gas temperatures these materials would allow with cooling. Adapted from N.P. Pature, Nature Materials.12 Credit: Adapted from N.P. Padture, Nature Materials.12

Fishman showed the progression of operating temperatures in an engine’s hot section during many years (Figure 3). Higher temperatures are attractive, because they improve operating efficiency by enhancing combustion and reducing cooling requirements. Coatings also allow for component life extension, because they protect the underlying superalloy substrate from excessive heat, reducing thermal degradation and allowing for their reutilization through stripping and recoating during overhaul and repair. By some measures, coatings as a life extension strategy is of critical importance, because cost has become an overriding driver in addition to performance.

Attack of TBCs and EBCs by environmental deposits, notably silica sand (e.g., desert sand, volcanic ash, and coal ash) that is ingested into flight engines, especially in dusty environments, was identified as a consensus issue at the workshop.16 Extensive studies have characterized deposits as a class of calcium magnesium aluminosilicate (CMAS) compounds with widely varied compositions. CMAS problems are relatively recent and are related to enhanced engine temperatures.

When turbine inlet temperatures are high, CMAS dust or debris that normally would cause erosion of the coating (progressive thinning) can melt and rapidly penetrate porosity and cracks within the coating. Resolidification of CMAS within the pores can compromise coating compliance, resulting in delamination failure during the cooling cycle. In addition, complex phase assemblage in various dust sources makes prediction of reactions more difficult.16 The porous nature of TBCs exacerbates this problem, compounded by the fact that most CMAS compositions do not react with yttria-stabilized zirconia, allowing the glassy liquid to penetrate all the way to the interface. CMAS has become the Achilles heel for continued enhancement of engine operational temperatures through use of TBCs.

Strategies to address the CMAS problem are twofold:

- Designing ceramic compositions that enable rapid reaction of CMAS, with the coating leading to formation of crystalline phases to immobilize it; and

- Generating precipitation products that block access of residual melt to the TBC’s interior.16 Researchers are investigating newer zirconia stabilizing elements, such as gadolinium, hafnium, and ytterbium, to provide greater resistance to CMAS attack.16 Fishman also discussed studies that suggest that MoSiB-based coatings on top of the TBC appear to restrict penetration of CMAS elements.17

Zhu discussed some of the issues associated with EBC bond coats on CMCs used in turbine and combustor applications. These EBC materials protect SiC structure composites via moisture-induced recession. EBCs are multilayered and are based on dense rare-earth silicate-based coatings, which are applied with appropriate barrier bond coats. Designing these coatings by incorporating materials with matching thermal expansion coefficients is critical, because EBCs, unlike TBCs, need to be crackfree and have very limited porosity. Although much of the activity is within the proprietary regime of industry, academic activities have focused on yttrium and ytterbium monosilicates and disilicates, which typically are applied via plasma spray.18

Zhu presented some new developments at NASA in using hafnium oxide-based coatings for greater resistance to degradation. He also discussed research on alternative processing techniques, such as directed vapor electron beam–physical vapor deposition (EB–PVD) and plasma spray physical vapor deposition, as a way to apply EBCs.19 CMAS effects continue to be front and center even for EBCs, especially because temperatures are even higher with concomitant reduction in the impinging glass viscosity.20

Coatings for reentry vehicles

Workshop attendees also discussed other types of coatings needed for thermal protection. Sylvia Johnson from the NASA Ames Research Center spoke about coatings for reusable entry systems. Johnson noted that flight conditions expected for future NASA missions require specific coating properties for reusable thermal protection systems. These include

- High-temperature capability;

- High-thermal-shock resistance;

- Property stability during many flights;

- High surface emittance and low reactivity;

- Low thermal expansion coefficient;

- Low thermal conductivity; and

- Minimum weight.

NASA currently is focused on a toughened unipiece reusable oxidation-resistant ceramic called TUFROC.21 Manufacturers can provide the material in various configurations that consists of a cap and an insulator base. The cap and the base consist of a high-temperature, low-density, carbonaceous, fibrous material that can be treated with a tantalum-based composite formulation. They can use the material on wing leading edges, nose area, and control surfaces for temperatures up to 3,100°F.

Future needs for ceramic coatings

We need a wide assortment of research to understand and control the existing set of growth templates, thin and thick films, interfacial layers, surfaces, and ceramic coatings to extend their usefulness, achieve new functionality, and foster creation of new materials. Areas of study include

- Examination of the degree of crystallinity (or amorphization);

- Effects of defects and impurities/doping;

- Computation and predictive modeling;

- Tuning and tailoring for specific applications;

- Strain modification and engineering; and

- Conversions (phase transformations) of sacrificial and barrier layers.

We also need to address practical concerns, such as processing simplifications, increased efficiency, and reduced cost. Researchers have a high calling to address the challenges facing society and to do so in a sustainable manner.22 For TBCs in particular, we need to develop new materials that are more resistant to CMAS attack while retaining the required resistance to fracture.

As highly controlled structures gain importance in practical applications, other aspects, such as surfaces and modeling, warrant more attention. For example, Laurence Marks23 of Northwestern University focuses specifically on oxide surfaces from bulk through nanoparticles—work that is broadly applicable to all ceramics. They share code with other users of Wien2k software24 and consequently can perform electronic structure calculations of solids using density functional theory with more than 2,000 groups in 84 countries, including developed, underdeveloped, and developing countries.

The ability to grow highly controlled, crystalline materials as large single crystals and as thin films is increasingly important. A recent academy report25 outlines the evolution and importance of materials with long-range periodicity of atomic positions for more functionality. NSF has answered this challenge through a new program called Materials Innovation Platforms (MIP), where equipment acquisition (up to $7 million) and development of tools and techniques are expected to result in new materials that should be transformative.

MIPs are five-year awards totaling $10–$25 million and may be renewed once. Darrell Schlom26 calls the new MIP award that he leads a mecca for materials discovery and envisions materials-by-design realization. The project seeks to advance understanding of oxide-based heterointerfaces with a range of 2-D material systems. The scientists expect to create novel electronic and magnetic functionalities, such as ferroelectricity, ferromagnetism, and superconductivity.

Another recently-funded MIP led by Joan Redwing27 focuses on 2-D chalcogenide materials for future electronics. Materials of particular interest include layered compounds that contain elements such as sulfur, selenium, and tellurium.

A recent article28 (resulting from an NSF workshop) outlines challenges in defining structure–property relations in films and confined 2-D ceramics (as well as bulk materials), controlling processing, working effectively with defects across time and length scales, creating ceramics for use under extreme conditions, and utilizing predictive modeling in design.

Lastly, manufacturing science of ceramic coatings is expected to be central in enabling applications. Given that many scalable coating deposition processes (vapor deposition, plasma spray, etc.) operate in extreme environments with significant nonequilibrium exposures, the process-structure–property interplay is highly complex and thus requires nontraditional scientific considerations, including coupling between experiments and modeling. Efforts such as integrated computational materials engineering that can extend beyond material design and performance to incorporate manufacturing attributes, such as process-property relationships and reliability engineering, will be key to transition advanced ceramics into applications.

Disclaimer

Any opinion, finding, recommendation, or conclusion expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NSF.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the many conversations with participants in the workshop and others on this topic.

Cite this article

S. W. Freiman, S. Sampath, and L. D. Madsen, “Protective and functional ceramic coatings—An interagency perspective,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2017, 96(7): 27–31.

About the Author(s)

Steve Freiman is president of Freiman Consulting (Potomac, Md.). Contact Freiman at steve.freiman@comcast.net. Lynnette D. Madsen is program director, ceramics, at the National Science Foundation (Arlington, Va.). Contact Madsen at lmadsen@nsf.gov. Sanjay Sampath is Distinguished Professor of Materials Science and Engineering and director of the Center for Thermal Spray Research at Stony Brook University (Stony Brook, N.Y.). Contact Sampath at sanjay.sampath@stonybrook.edu.

Issue

Category

- Engineering ceramics

Article References

1S.W. Freiman, L.D. Madsen, and J.W. McCauley, “Advances in ceramics through government-supported research,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull., 88 [1] 27–31 (2009).

2S.W. Freiman, L.D. Madsen, and J. Rumble, “A perspective on materials databases,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull., 90 [2] 28–32 (2011).

3S.W. Freiman and L.D. Madsen, “Issues of scarce materials in the United States,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull., 91 [4] 40–45 (2012).

4S.W. Freiman and L.D. Madsen, “The state of ceramic education in the United States and future opportunities,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull., 94 [2] 34–38 (2015).

5S.W. Freiman, L.D. Madsen, and W. Hong, “Computation and modeling applied to ceramic materials,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull., 95 [3] 36–40 (2016).

6J.E Greene, “Tracing the 5000-year recorded history of inorganic thin films from similar to 3000 BC to the early 1900s AD,” Appl. Phys. Rev., 1, 041302 (2014).

7W.N. Harrison, D.G. Moore, and J.C. Richmond, “Review of an investigation of ceramic coatings for metallic turbine parts and other high-temperature applications,” Technical Note 1186, National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, Washington, D.C., 1947.

8S. Stecura, “Two-layer thermal barrier coating for turbine airfoils—Furnace and burner rig test results,” NASA TM X-3425, Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 1976.

9R.A. Miller, “History of thermal barrier coatings for gas turbine engines,” NASA/TM 2009-215459, Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 2009.

10C.R. Morse, “Comparison of National Bureau of Standards ceramic coatings L-7C and A-417 on turbine blades in a turbojet engine,” NACA Research Memo E8120, Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 1948.

11L.N. Hjelm and B.R. Bornhorst, “Development of improved ceramic coatings to increase the life of XLR99 thrust chamber,” NASA TM X-57072, Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 1961.

12N.P. Padture, “Advanced structural ceramics in aerospace propulsion,” Nat. Mater., 15, 804–809 (2016).

13D.R. Clarke, N.P. Padture, and M. Oechsner, Eds., “Thermal-barrier coatings for more efficient gas-turbine engines,” MRS Bull., 37 [Oct.] (2012).

14S. Sampath, W.B. Choi, G. Dwivedi, and A. Valarezo, “Partnership for accelerated insertion of new technology: Case study for thermal spray,” Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov., 2:1 (2013) doi:10.1186/2193-9772-2-1

15S. Sampath, unpublished work.

16C.G. Levi, J.W. Hutchinson, M.-H. Vidal-Setif, and C. Johnson, “Environmental degradation of thermal barrier coatings by molten deposits,” MRS Bull., 37 [10] 932–41 (2012).

17J.H. Perepezko, T.A. Sossaman, and M. Taylor, “Environmentally resistant Mo-Si-B-based coatings,” J. Therm. Spray Technol. 26, 929–40 (2017).

18B.T. Richards and H. Wadley, “Plasma spray deposition of tri-layer environmental barrier coatings,” J. Eur. Ceram. Soc., 34, 3029–83 (2014).

19D. Zhu, “Advanced environmental barrier coatings for SiC/SiC ceramic-matrix composite turbine components”; pp. 187–202 in Engineered Ceramics: Current Status and Future Prospects. Edited by T. Ohji and M. Singh. Wiley, New York, 2016.

20D. Poerschke, D. Haas, S. Estis, G. Seward, J. Van Slutman, and C. Levi, “Stability and CMAS resistance of ytterbium silicate EBCs/TBCs for SiC composites,” J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 98 [1] 278–86 (2015).

21https://technology.nasa.gov//t2media/tops/pdf/TOP2-241.pdf

22L.S. Sapochak and L.D. Madsen, “Editorial: A material world,” Open Science EU, ISSN 2397-7582, pp. 8–11 (June 2016).

23http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1507101

24http://susi.theochem.tuwien.ac.at

25National Research Council, “Frontiers in Crystalline Matter: From Discovery to Technology.” National Acadamies Press, Washington, D.C., 2009. https://doi.org/10.17226/12640.

26https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1539918

27https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1539916

28K.T. Faber, et al., “The role of ceramic and glass science research in meeting societal challenges: Report from an NSF-sponsored workshop,” J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 100, 1777–1803 (2017).

Related Articles

Market Insights

Engineered ceramics support the past, present, and future of aerospace ambitions

Engineered ceramics play key roles in aerospace applications, from structural components to protective coatings that can withstand the high-temperature, reactive environments. Perhaps the earliest success of ceramics in aerospace applications was the use of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) as thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) on nickel-based superalloys for turbine engine applications. These…

Market Insights

Aerospace ceramics: Global markets to 2029

The global market for aerospace ceramics was valued at $5.3 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.0% to reach $8.2 billion by the end of 2029. According to the International Energy Agency, the aviation industry was responsible for 2.5% of…

Market Insights

Innovations in access and technology secure clean water around the world

Food, water, and shelter—the basic necessities of life—are scarce for millions of people around the world. Yet even when these resources are technically obtainable, they may not be available in a format that supports healthy living. Approximately 115 million people worldwide depend on untreated surface water for their daily needs,…