As nonequilibrium materials, glasses continuously relax toward the supercooled liquid metastable equilibrium state.1,2 Although the myth of flowing glasses in cathedrals suggests otherwise,3 the dramatic increase of glass viscosity with decreasing temperature renders relaxation effectively “frozen” at ambient temperature. However, specific glass compositions can surprisingly deform over time, even at low temperature. This phenomenon is known as the thermometer effect1,4 and is usually attributed to the mixed-alkali effect, which occurs in oxide glasses comprising at least two alkali oxides, AO2 and BO2, and manifests as a nonlinear evolution of properties with respect to the fraction A/(A + B).

Despite its practical importance,5 we continue to poorly understand the nature of relaxation in the glassy state. To date, no clear atomistic mechanism of structural and stress relaxation is available, which seriously limits our ability to predict and control behavior.6 This knowledge gap becomes even more problematic as the need for large screens with higher resolution (smaller pixel size) results in lower tolerances for relaxation and novel LCD fabrication processes (e.g., p-Si applications) require use of higher processing temperatures, further enhancing relaxation.5 Addressing these grand challenges7 requires a better understanding of the fundamentals of glass relaxation.

Accelerated relaxation technique

To investigate the mixed-alkali effect in glass relaxation, we simulated a series of (K2O)x(Na2O)16–x(SiO2)84 (mol%) mixed-alkali silicate glasses, made of 2,991 atoms, with varying x (x = 0–16). We performed molecular dynamics simulations using the well-established Teter potential8–10 with an integration timestep of 1 fs. We evaluated Coulomb interactions using the Ewald summation method with a cutoff of 12 Å and chose a short-range interaction cutoff of 8.0 Å.

We generated liquids by placing atoms randomly in a simulation box. We then equilibrated liquids at 5,000 K in the isothermal–isobaric (NPT) ensemble (where the number of atoms (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T) are conserved) for 1 ns, at zero pressure, to ensure loss of the memory of initial configuration. We formed glasses by linear cooling of liquids from 5,000 to 0 K, with a cooling rate of 1 K/ps in the NPT ensemble at zero pressure.

To simulate long-term relaxation of these glasses, we relied on an accelerated simulation technique that we recently developed to understand the origin of room-temperature relaxation in Corning Gorilla Glass.1,4 In that method, simulated glass is subjected to small, cyclic perturbations of volumetric stress. This method mimics the relaxation observed in granular materials subjected to vibrations,11 wherein small vibrations tend to densify the material (artificial aging) and large vibrations randomize grain arrangements (rejuvenation).

Researchers have applied similar ideas relying on the energy landscape approach12 to noncrystalline solids based on the fact that small stresses deform the energy landscape locally explored by atoms. This can remove some energy barriers that exist at zero stress, thus allowing the system to jump over barriers to relax to lower energy states. Yu et al. provide more details about this method.1

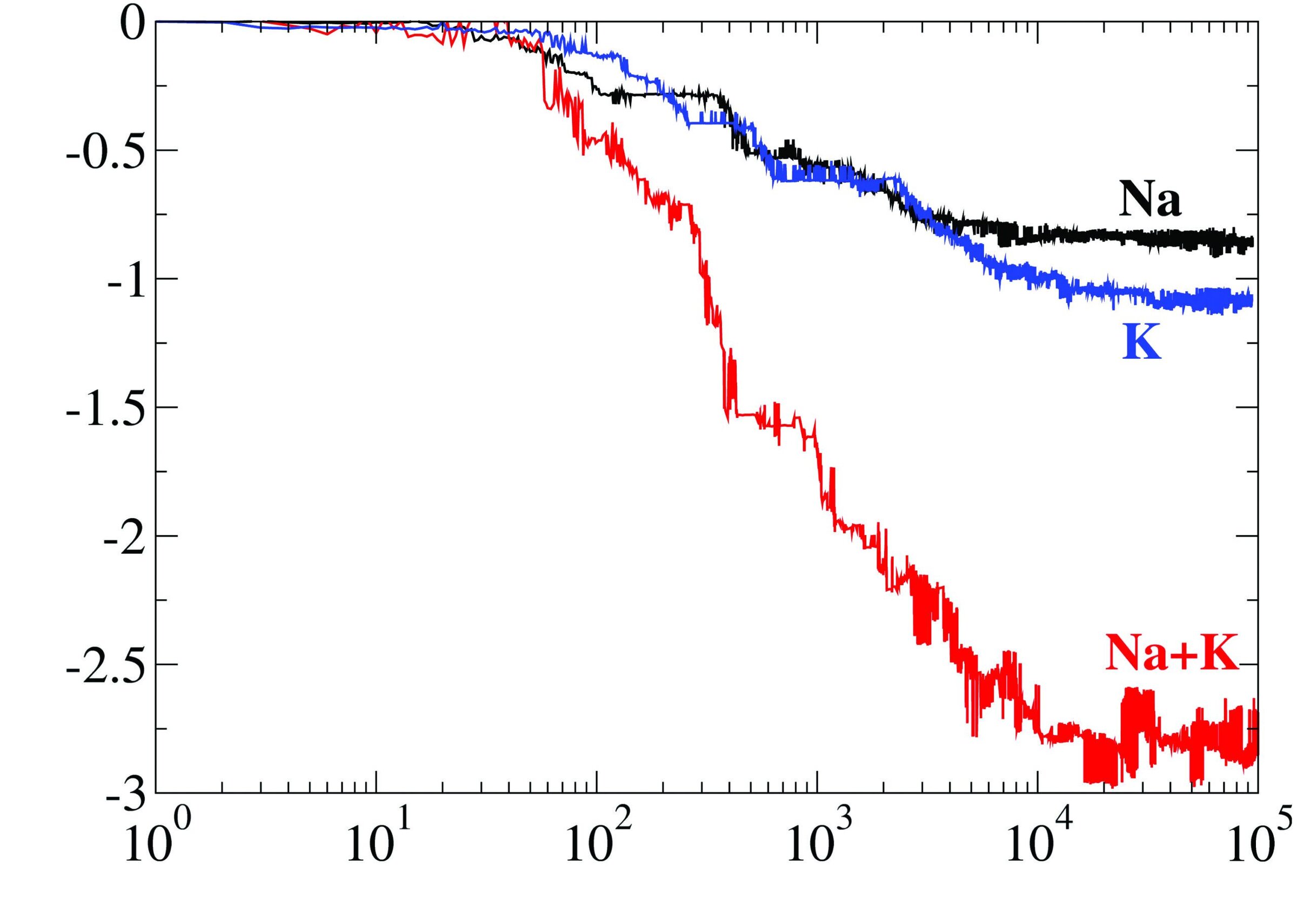

As expected, stress perturbations allow all glasses to relax toward lower energy states.1 All glasses tested here showed a gradual compaction in volume upon relaxation (Figure 1). Remarkably, the volume relaxation observed herein followed a stretched exponential decay function that is similar to that observed experimentally.4 Further, the mixed (K2O)8(Na2O)8(SiO2)84 glass featured a larger densification than binary sodium and potassium silicate glasses. This is a clear demonstration that the thermometer effect is indeed a manifestation of the mixed-alkali effect.

Figure 1. Relative variation of the volume of sodium, potassium, and mixed-alkali silicate glasses with respect to the number of stress perturbation cycles applied. Credit: Yingtian Yu

Origin of the mixed-alkali effect in relaxation

We also investigated the origin of the mixed-alkali effect in the context of relaxation. We can predict the stretched exponential nature of glass relaxation using the Phillips diffusion-trap model, wherein “excitations” in the glass diffuse toward randomly distributed “traps.”13 However, this model remains largely axiomatic. Here, we propose that excitations introduced within the diffusion-trap model correspond to locally unstable atomic units.

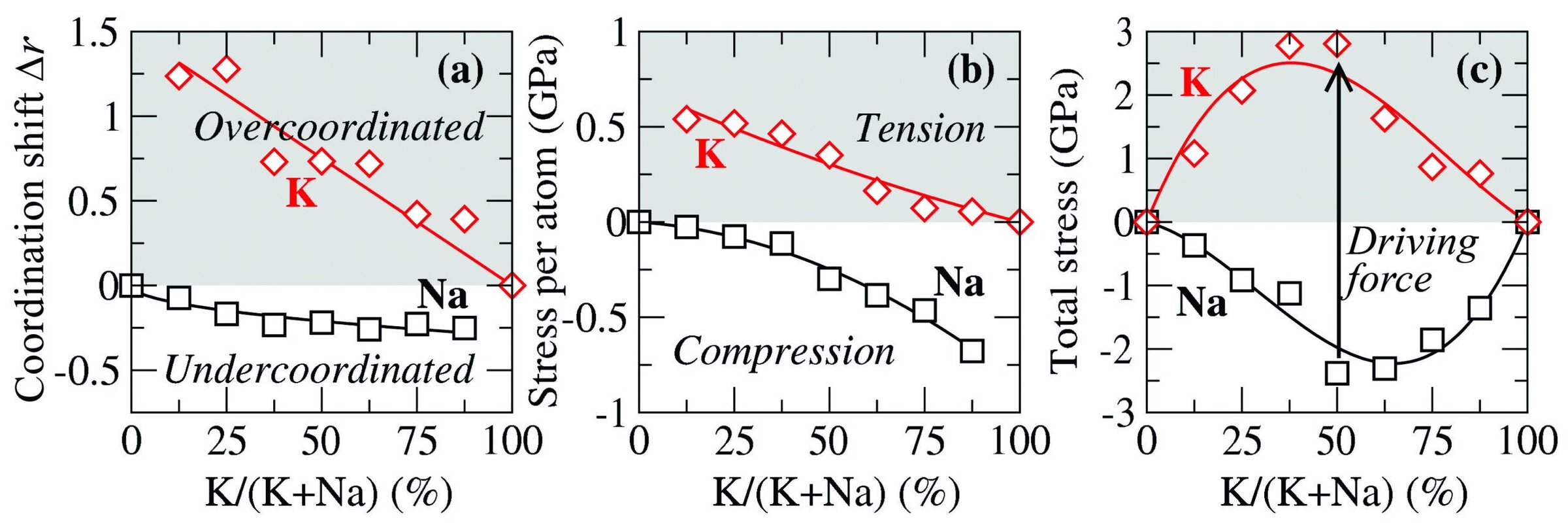

Figure 2. (a) Shift of the coordination number of sodium (potassium) atoms, using the binary sodium (potassium) silicate glass as a reference, with respect to composition of the glass. (b) Average stress per sodium and potassium atoms. A positive (negative) stress denotes local compression (tension). (c) Total cumulative stress experienced by all sodium and potassium atoms. Credit: Yingtian Yu

To assess this hypothesis, we first computed the coordination number of all atomic species. Figure 2(a) shows that the coordination number of sodium decreases upon addition of potassium, whereas that of potassium increases upon addition of sodium—which we attribute to mismatch between alkali atoms and the rest of the silicate network as we move away from the binary composition. This miscoordinated state forms local stresses inside the atomic network, which we assessed by computing the local stress applied to each atom.14 Figure 2(b) shows that the average stress experienced by sodium atoms increases upon addition of potassium, whereas that experienced by potassium atoms decreases upon addition of sodium.

We explain this as follows.

Overcoordinated potassium atoms present an excess of oxygen atoms in their first coordination shell. Because of mutual repulsion, oxygen atoms tend to separate from each other, which, in turn, tends to stretch the potassium–oxygen bonds. On the other hand, undercoordinated sodium atoms show a deficit of oxygen atoms, which, in turn, are more attracted by the central cation. This results in compression of sodium–oxygen bonds.

We then explain the mechanism of glass relaxation as follows.

Miscoordinated species act as local instabilities (or “excitations” following Phillips terminology). These excitations diffuse via local deformations of the atomic network, until an atomic arrangement that is locally under compression meets one that is under tension. At this point, both excitations are annihilated (or reach a “trap”), thereby relieving initial internal stress stored in the network.

The driving force for relaxation corresponds to the difference between total cumulative stress experienced by sodium and potassium atoms, which results from the balance between two competitive behaviors. In the first behavior, absolute stress per atom experienced by sodium and potassium species increases upon addition of potassium and sodium, respectively. In contrast, in the second behavior, numbers of sodium and potassium atoms present in the network decrease upon their replacement by potassium and sodium atoms, respectively. Altogether, total cumulative stress experienced by sodium and potassium atoms reaches a maximum when the number of sodium atoms equals the number of potassium atoms (Figure 2(c)). This behavior provides an intuitive atomistic origin of the excessive volume relaxation of glasses comprising mixed alkali atoms (i.e., thermometer effect).

In future work, we plan to extend analyses to mixed-alkaline-earth silicate glasses to assess the generality of these results. Besides relaxation, we also plan to investigate the effect of local atomic instabilities evidenced herein on the mechanical properties of glasses.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1562066 and Corning Incorporated.

Editor’s note

Yu will present the 2017 Kreidl Award Lecture at the Glass and Optical Materials Division Annual Meeting, during the Pacific Rim Conference on Ceramic and Glass Technology, in Waikaloa, Hawaii, on May 24, 2017.

Cite this article

Y. Yu, J. C. Mauro, and M. Bauchy, “Stretched exponential relaxation of glasses: Origin of the mixed-alkali effect,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2017, 96(4): 34–36.

About the Author(s)

Yingtian Yu and Mathieu Bauchy are members of the Physics of AmoRphous and Inorganic Solids Laboratory (PARISlab) at the University of California (Los Angeles, Calif.). Bauchy is assistant professor, Civil Engineering Materials at UCLA. John C. Mauro is senior research manager—Glass Research at Corning Incorporated (Corning, N.Y.). Contact Yu at yuyingti@ucla.edu.

Issue

Category

- Glass and optical materials

Article References

1Y. Yu, M. Wang, D. Zhang, B. Wang, G. Sant, and M. Bauchy, “Stretched exponential relaxation of glasses at low temperature,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 115 [16] 165901 (2015).

2A.K. Varshneya, Fundamentals of Inorganic Glasses. Elsevier, San Diego, Calif, 1993.

3E.D. Zanotto, “Do cathedral glasses flow?,” Am. J. Phys., 66 [5] 392–95 (1998).

4R.Welch, J. Smith, M. Potuzak, X. Guo, B. Bowden, T. Kiczenski, D. Allan, E. King, A. Ellison, and J. Mauro, “Dynamics of glass relaxation at room temperature,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 110 [26] 265901 (2013).

5A.Ellison and I.A. Cornejo, “Glass substrates for liquid crystal displays,” Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci., 1 [1] 87–103 (2010).

6J.C. Mauro, C.S. Philip, D.J. Vaughn, and M.S. Pambianchi, “Glass science in the United States: Current status and future directions,” Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci., 5 [1] 2–15 (2014).

7J.C. Mauro and E.D. Zanotto, “Two centuries of glass research: Historical trends, current status, and grand challenges for the future,” Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci., 5 [3] 313–27 (2014).

8A.N. Cormack, J. Du, and T.R. Zeitler, “Alkali-ion migration mechanisms in silicate glasses probed by molecular dynamics simulations,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 4 [14] 3193–97 (2002).

9M. Bauchy, “Structural, vibrational, and thermal properties of densified silicates: Insights from molecular dynamics,” J. Chem. Phys., 137 [4] 44510 (2012).

10M. Bauchy, B. Guillot, M. Micoulaut, and N. Sator, “Viscosity and viscosity anomalies of model silicates and magmas: A numerical investigation,” Chem. Geol., 346, 47–56 (2013).

11P. Richard, M. Nicodemi, and R. Delannay, “Ribites and magmas: A numeric slow relaxation and compaction of granular systems,” Nat. Mater., 4 [2] 121–28 (2005).

12D.J. Lacks and M.J. Osborne, “Energy landscape picture of overaging and rejuvenation in a sheared glass,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 93 [25] 255501 (2004).

13J.C. Phillips, “Stretched exponential relaxation in molecular and electronic glasses,” Rep. Prog. Phys., 59 [9] 1133 (1996).

14A.P. Thompson, S.J. Plimpton, and W. Mattson, “General formulation of pressure and stress tensor for arbitrary many-body interaction potentials under periodic boundary conditions,” J. Chem. Phys., 131 [15] 154107 (2009).

Related Articles

Market Insights

Engineered ceramics support the past, present, and future of aerospace ambitions

Engineered ceramics play key roles in aerospace applications, from structural components to protective coatings that can withstand the high-temperature, reactive environments. Perhaps the earliest success of ceramics in aerospace applications was the use of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) as thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) on nickel-based superalloys for turbine engine applications. These…

Market Insights

Aerospace ceramics: Global markets to 2029

The global market for aerospace ceramics was valued at $5.3 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.0% to reach $8.2 billion by the end of 2029. According to the International Energy Agency, the aviation industry was responsible for 2.5% of…

Market Insights

Innovations in access and technology secure clean water around the world

Food, water, and shelter—the basic necessities of life—are scarce for millions of people around the world. Yet even when these resources are technically obtainable, they may not be available in a format that supports healthy living. Approximately 115 million people worldwide depend on untreated surface water for their daily needs,…