Cultivating engineers and opportunities

A conversation with Gabrielle Gaustad, dean of the Inamori School of Engineering at Alfred University

Young women entering the Inamori School of Engineering at Alfred University do not have to search far for a role model in a traditionally male-dominated field. The dean of the school, Gabrielle Gaustad, was once a first-year student there herself.

“I’m a product of our program: a ceramic engineering undergrad from Alfred University,” she says. “Alfred has a great record of having women in the program. It was great for me as an undergrad to have a lot of female faculty and students around me. I didn’t see a gap until I got out in the workforce.”

Gaustad earned a Ph.D. in materials science and engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then worked in the aluminum and steel industries from both the waste management and manufacturing sides. She describes this time as “eye-opening” in terms of gender imbalances. Today, she sees diversity as something that needs to begin “even earlier than college” with outreach efforts that create more opportunities for students in less affluent school districts that are not equipped to offer advanced placement studies in subjects such as chemistry and physics.

Working to overcome disadvantages

“Those educational gaps probably start pretty young, and by the time the students enter college, there is not a ton we can do about those gaps,” she says. “We have a couple programs for students that are a little bit on the bubble. We want to admit them, but we’re worried that they might not have everything they need. We have some summer programming that brings them on campus early to see if we can identify gaps and try to fill them before they start as an engineer in the fall.”

But economic circumstances can continue to have an impact even when students are succeeding in the program. There are relocation costs associated with accepting internships, such as securing housing and transportation. The school has tried to address these challenges through a summer research opportunity program that provides housing and a competitive stipend to cover other costs.

“I think that program has increased accessibility, so that if you have an economically disadvantaged background, you can take advantage of that opportunity,” Gaustad says. “And now we’re seeing a lot more internships that are providing housing along with the stipend, which again lowers barriers to accessibility for all students.”

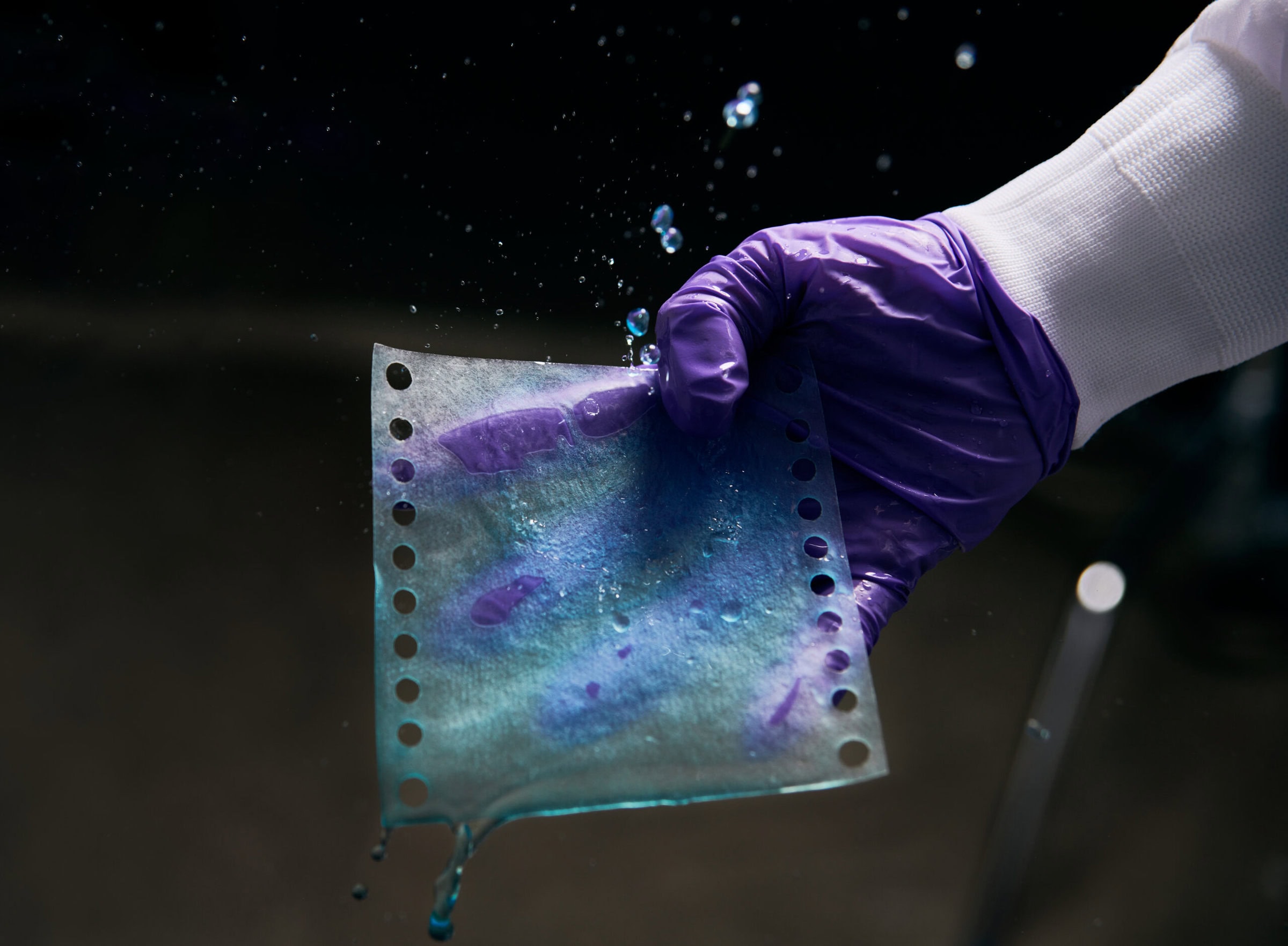

Temitope (Temmy) Adeloye, an undergraduate student majoring in materials science and engineering at Alfred University, participates in the university’s summer research opportunity program. Credit: Caitlin Brown, Alfred University

Powering up next-generation engineers

The school keeps track of which industries are hiring and which have seen student recruitment decline. Big growth sectors right now include aerospace, renewable energy, and semiconductors, including advanced ceramics and glass or “anything computer or semiconductor adjacent,” Gaustad says. Conversely, there are reduced opportunities for students hoping to enter automotive and traditional manufacturing.

Gaustad’s students prioritize ongoing training and professional development, although the specifics of what that can mean varies by student and industry.

“A lot of our engineers will end up going through some kind of management track, but maybe they didn’t have opportunities to take a business or management course during their undergraduate study,” she says. “So, they’re looking for leadership training, mentorship, and management training because that shows you do have a pathway toward leadership or management roles.”

Championing the environment and entrepreneurship

As they transition from campus to careers, Gaustad sees students demonstrating a “super strong interest” in culture that includes sustainability. Plus, they can see through greenwashing.

“Companies that are using ESG [environmental, social, governance] metrics purely for marketing purposes? They’re pretty savvy about that kind of thing,” she says.

That awareness dovetails with her own work, which includes a decade and a half dedicated to recycling materials. At Alfred, that translates to a large glass recycling project conducted in connection with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. She also works on a project with the Army Research Laboratory to develop ultrahigh-temperature ceramic materials. Gaustad estimates that 40 undergraduates worked on those and other projects during summer 2024.

Students also enter school-organized pitch competitions to raise interest in entrepreneurship and working at startups.

“A few students have had success with that—starting a company, making some products, and doing well,” Gaustad says. “We’re probably just touching the tip of the iceberg, and we could grow that substantially.”

From classroom to commercialization

A conversation with Michel Barsoum, Distinguished Professor of materials science and engineering at Drexel University

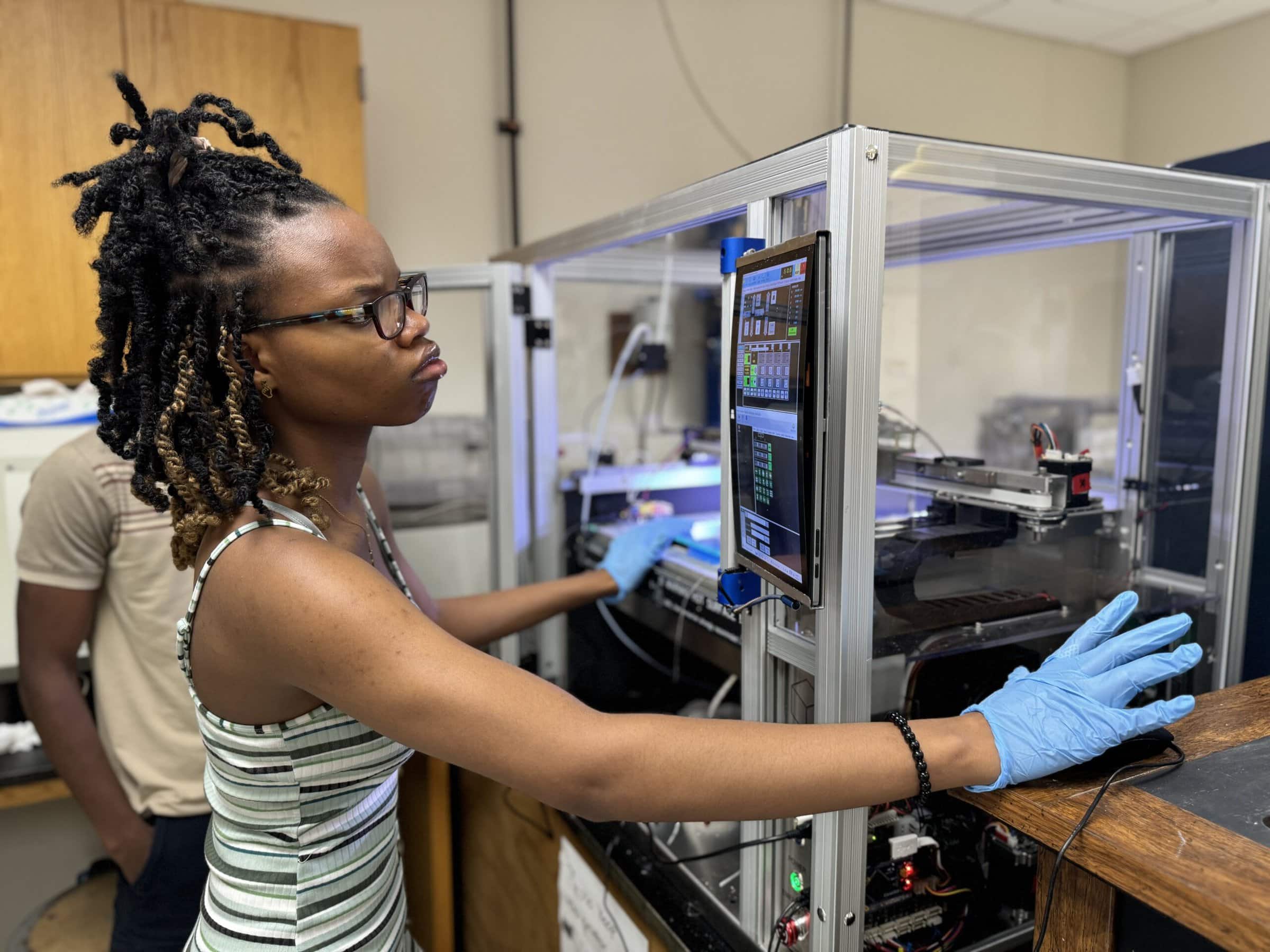

Michel Barsoum in his lab at Drexel University. He says that many students in recent years demonstrate an entrepreneurial mindset, which he tries to help foster through his research. Credit: Michel Barsoum

On July 3, 2024, Drexel University announced that One-D Nano, a nanomaterial clean technology company, would receive a $150,000 investment from the Drexel University Innovation Fund, which was created to provide start-up capital for the commercialization of innovations and technologies that originated at the school.4

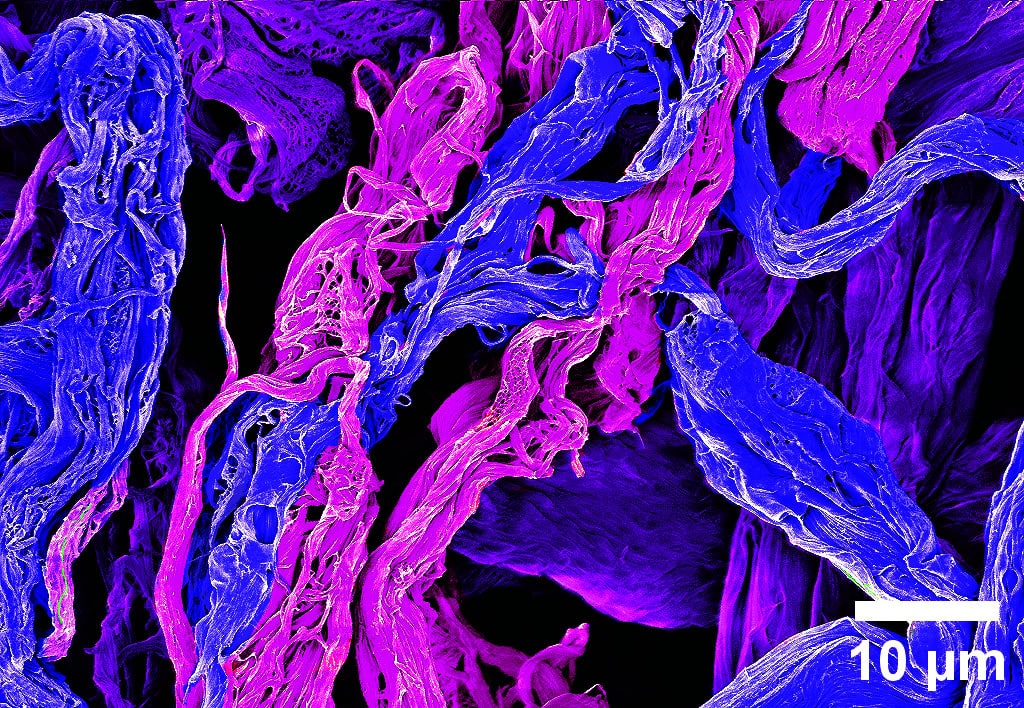

The news follows the discovery in 2022 of one-dimensional nanofilaments by Michel Barsoum, Distinguished Professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and Hussein Badr, then a doctoral researcher in the Layered Solids Group, which Barsoum leads.

As the July 3 announcement explains, they believe these nanofilaments, which they labeled 1DL, have the capacity to “help sunlight glean hydrogen from water for months at a time to significantly reduce the cost of green hydrogen.”

Barsoum is co-founder and technical advisor to One-D Nano, which was launched to commercialize 1DLs with his postdoctoral fellow, Greg Schwenk, who will serve as the company’s CEO. Recently, Schwenk was also chosen from a field of more than 1,000 applicants for the prestigious Activate Fellowship,5 a program with a rich history of cultivating success from hard tech startups spun out of university labs. This award will provide Schwenk with roughly $500,000 over two years that he can use to help build up the company.

But 1DL’s potential for environmental impact is just part of the story, in Barsoum’s view. He finds it equally exciting that it is a material that can literally be made in a kitchen at minimal cost.

“The combination of using inexpensive starting material, the ease with which we can make the stuff, and the ease with which we can scale it is quite remarkable,” he says. “We think we can make it in large quantities, and a lot cheaper than any other nanotech out there. That’s the business proposition.”

Encouraging and financing entrepreneurs

The Drexel University Innovation Fund recognizes projects with potential for “addressing the world’s most pressing challenges,” and all returns on investments revert to the fund so they can be awarded to future start-ups.6 The program also seeks to provide students with hands-on experience in the venture capital arena. That strategy meshes neatly with the entrepreneurial mindset Barsoum sees in many of his students.

“I think this young generation, even at the undergraduate level, sees that as a possibility,” he says. “They watch other people become millionaires and billionaires at age 30. That is a pretty strong incentive to start a company and sell it.”

He says faculty members are responsible for initiating that innovation, but he also recognizes the importance of institutional and financial backing. Neither form of support was available when he launched start-ups between 10 and 20 years ago, a time that he describes as more ad hoc. Today’s approach aligns with his sense of responsibility for preparing the next generation of scientists to take their place in the world as well as his own professional goal to make a difference in meeting global challenges, such as sequestering CO2 and rendering non-potable water safe to drink.

Acknowledgment and ambition

Barsoum’s success in making a difference was recognized on June 18, 2024, at a ceremony that marked his induction as a Fellow of the National Academy of Inventors. He describes that recognition as “the cherry on the cake” but says curiosity and the desire to “solve big problems” have always been his primary motivations.

“Every day I go to work and shake my head. I can’t believe they pay me to do this,” he says. “I tell my students, ‘You know, graduate school is supposed to be fun. If you’re not having fun, and I’m serious, let me know because something’s wrong.’”

Return to main article: “United States of America: Market giant with great expectations“

Scanning electron microscope micrograph showing the morphology of a one-dimensional titania-based material when the water in the colloid suspension is mixed with a solvent. Credit: . Scanning electron microscope micrograph taken by G. Schwenk and artistically rendered by Patricia Lyons of Moorestown, N.J.

Cite this article

R. B. Hecht, “United States of America: Market giant with great expectations,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2024, 103(8): 20–29.

Issue

Category

- International profiles

Article References

4L. Campion, “Drexel materials start-ups receive Innovation Fund investments,” Drexel University. Published 3 July 2024. Accessed 20 Aug. 2024.

5“Introducing Cohort 2024,” Activate.

6The Drexel University Innovation Fund, https://drexel.edu/applied-innovation/funding/innovation-fund

Related Articles

Bulletin Features

The nonferrous metals market: Supply and regulatory pressures inspire strategies for a resilient future

Nonferrous metals serve foundational roles in the electrification, renewable energy, and digital transformation. Nonferrous metals are metals that do not contain iron in significant amounts. These metals typically are nonmagnetic, corrosion resistant, electrically and thermally conductive, and lightweight, making them ideal for applications in the emerging markets mentioned above. Even…

Market Insights

Industrial digitalization: ‘Smart’ operations can improve worker safety and well-being in high-temperature environments

Heavy industry is the backbone of economies around the world, critical to automotive production, construction, the energy sector, and everything in between. But many heavy industries are facing worker shortages. There are more than 400,000 open manufacturing jobs in the United States, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.1 With…

Market Insights

‘Fail fast’ manufacturing: How disciplined experimentation strengthens, not threatens, quality

In manufacturing, few phrases raise eyebrows faster than “fail fast.” In the startup world, this business strategy is celebrated as a sign of agility. On a ceramic manufacturing floor, it can sound careless or even dangerous. In manufacturing, few phrases raise eyebrows faster than “fail fast.” In the startup world,…