The rapid advancement of industrial and technological innovations has demanded simultaneous innovation in the materials landscape to meet these emergent needs. Yet many base materials are already utilized at or near their theoretical performance limits.

To overcome this seemingly immutable barrier, functional fillers have emerged as a promising method to drive innovations in established material systems. Filler materials can modify existing composites to enhance the properties of the overall system thanks to their own exceptional properties, which can include superb mechanical strength, extreme chemical and oxidative resistance, variable thermal conductivity, and tunable electrical conductivity.

Traditional fillers typically have dimensions on the micrometer scale, including talc, glass fibers, and carbon black. However, many of these microfillers require high loading levels (up to 50 wt.%) and suffer from effects due to interfacial matrix mismatch or decreased matrix interaction.

Nanofillers are an emerging category of filler materials with at least one dimension on the nanometer scale. They are powerful alternatives to microfillers due to their extremely high surface-to-volume ratio, which allows for much stronger interfacial interaction with the matrix material. This improved interaction between filler and matrix leads to significant mechanical, thermal, or barrier property enhancements and are achievable at loading levels of only 1–5 wt.% or lower.

In addition to enhanced properties, the reduced loading level of nanofillers enables retention of many of the desirable properties inherent to the host matrix, such as processability and toughness. These lower loading levels also avoid excessive weight or density increases, which can make the overall material unusable in tailored applications. An additional advantage of the low weight loading is economic—it leads to lightweighting and minimizing cost of the final product while delivering optimized properties for the overall composite material.

The choice of nanofiller depends on the desired balance of mechanical, thermal, electrical, and barrier properties. Currently, several nanofillers are commonly used within the materials industry to create high-performance materials:

- Graphene is inherently a 2D nanofiller, as it exists as a sheet structure composed of just one or a few atomic layers. Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) can be exfoliated or synthesized to similar dimensions. Both graphene and hBN offer enhanced mechanical strength and thermal conductivity.

- Nanoclays, which are 2D silicate platelets, excel primarily as barrier enhancers that impede gas and liquid permeation and enhance flame retardancy.

- Metal oxide nanoparticles are typically 0D, meaning all their physical dimensions are on the nanometer scale. They are utilized for specific functionalities, such as ultraviolet absorption and catalytic or electronic activity.

The 2D platelets and 0D nanoparticles listed above are currently the most common morphologies of nanofillers. However, 1D tubular morphologies, i.e., nanotubes, have emerged as prime candidates for highly functional nanofillers.

Like other nanofillers, 1D tubular morphologies have an extremely high surface-to-volume ratio. But a distinct benefit of 1D nanofillers lies in their balance between high surface area and low effective dosing rates. In other words, a small number of long tubes can bridge the entire matrix, forming a continuous network for electrical current, heat transfer, or mechanical stress transfer more easily than stacked 2D flakes or dispersed 0D spheres.

Evidence of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) has been found in certain historical steels and pottery coatings, but the first intentional synthesis of CNTs was demonstrated by Iijima et al. in 1991.1 This discovery marked a pivotal moment in nanoscience.

The structure of CNTs is typically described as a 2D graphene nanosheet cut into a ribbon and rolled into a 1D tube. While this description effectively communicates their hexagonal lattice structure, it is misleading because CNTs are typically synthesized from the bottom up using gaseous precursor materials. Structurally, CNTs can be synthesized as either single-walled carbon nanotubes (consisting of a single seamless graphene cylinder) or as multiwalled carbon nanotubes (concentric cylinders of graphene separated by less than 1 nm).

CNTs were initially explored for use in electronics as transistors, a potential application rooted in their electrically conductive properties. Their application remained limited to niche markets for many years, but in the past decade, advancements in synthesis techniques, particularly large-scale chemical vapor deposition and the optimization of metal catalysts, enabled their mass production at a manageable cost. CNTs are now routinely used as nanofillers to create products ranging from electrically conductive plastics in electronics and automotive parts to mechanically reinforced materials in textiles, solar panels, and high-performance sports equipment, resulting in an annual market volume measured in tens of thousands of tons.

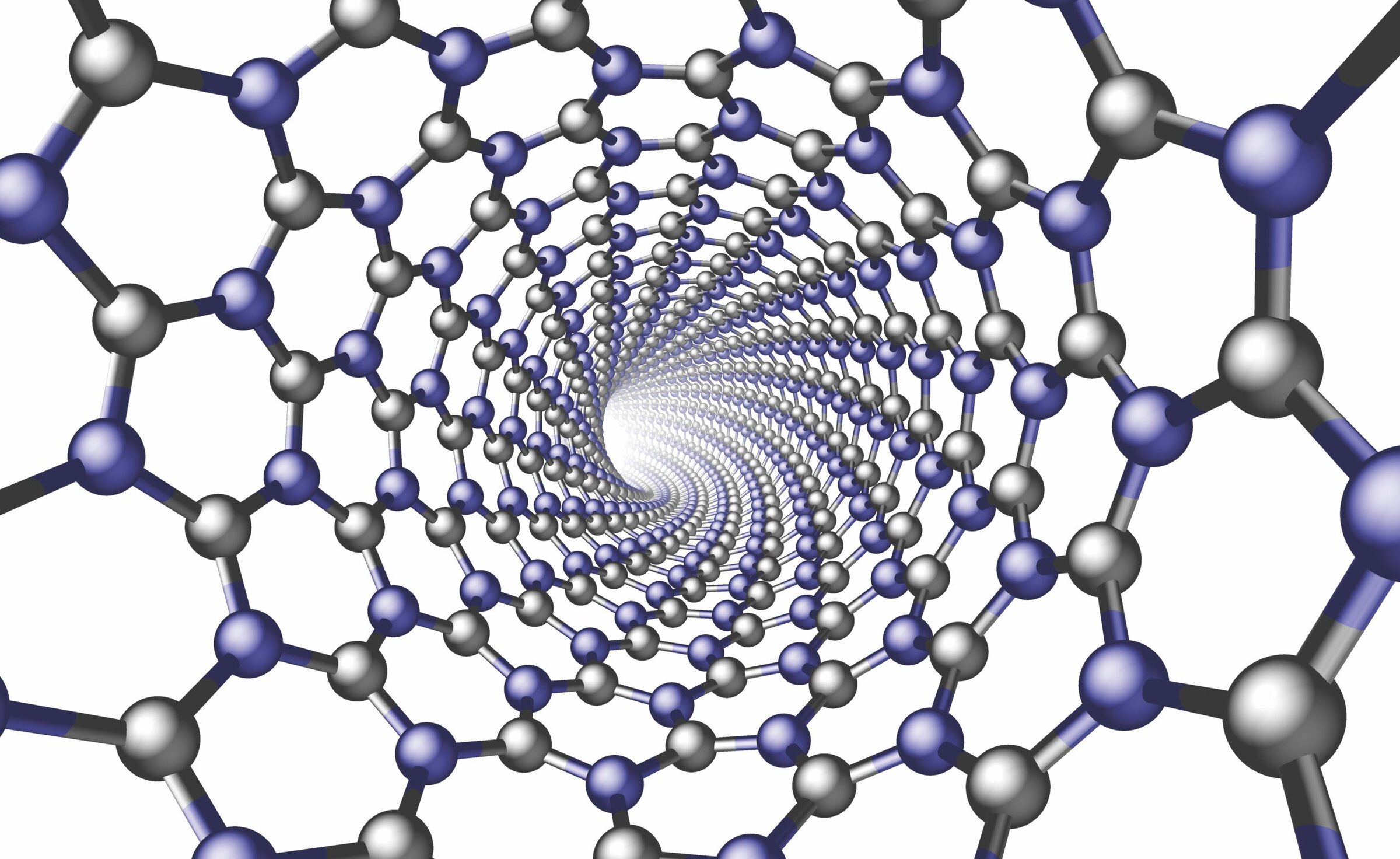

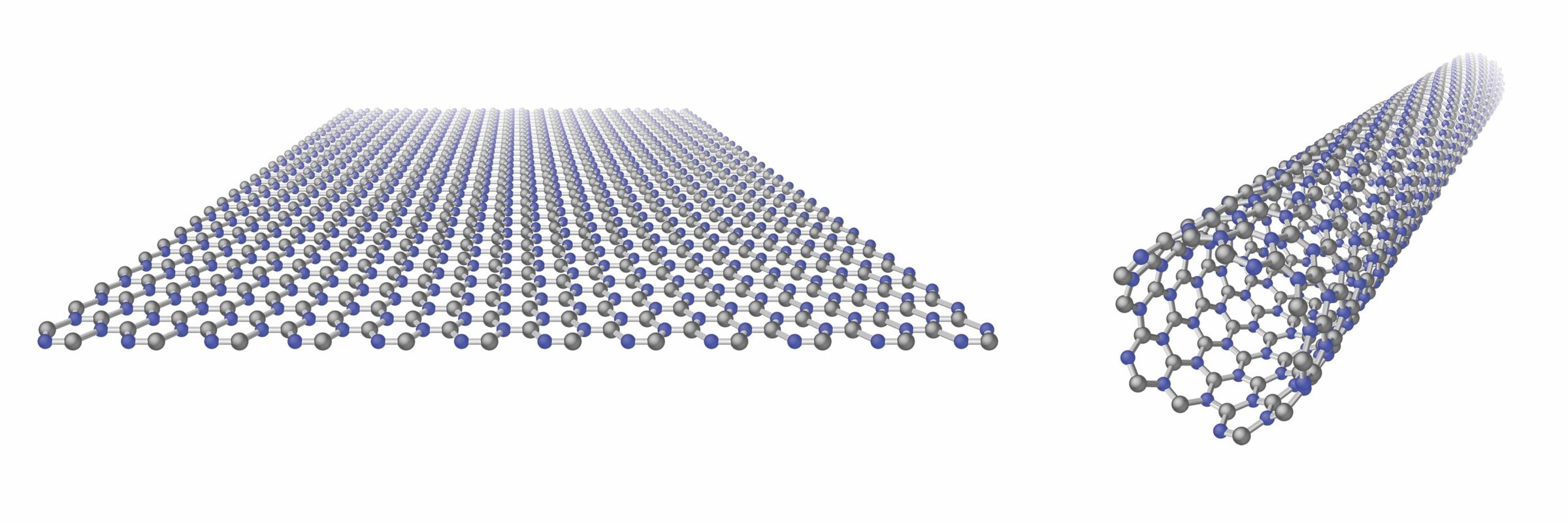

Recently, boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) have garnered interest as a highly functional nanofiller. Just as the structure of CNTs can be imagined as rolled graphene sheets, the structure of BNNTs can be similarly imagined as rolled nanosheets of hBN (Figure 1), consisting of alternating boron and nitrogen atoms in a hexagonal lattice.2

Figure 1. Molecular structure of a) hexagonal boron nitride and b) boron nitride nanotubes. Blue and grey atoms represent nitrogen and boron, respectively. Credit: Epic Advanced Materials

BNNTs were originally synthesized by Chopra at al. in 1995,3 who predicted their creation based on the structural similarities of graphene and hBN. But even though the initial discovery of BNNTs followed only a few years after CNTs, there has been a distinct difference in the trajectory of scale up and industrial adoption of these materials. The market globally for CNTs has reached tens of thousands of tons annually, while BNNTs are only on the scale of tens of kilograms.

This article will shine a light on the factors driving the growth trajectory of BNNTs and describe the recent breakthroughs that enable BNNTs to now stand at the cusp of transforming the advanced materials landscape.

Structure–property relationships of BNNTs

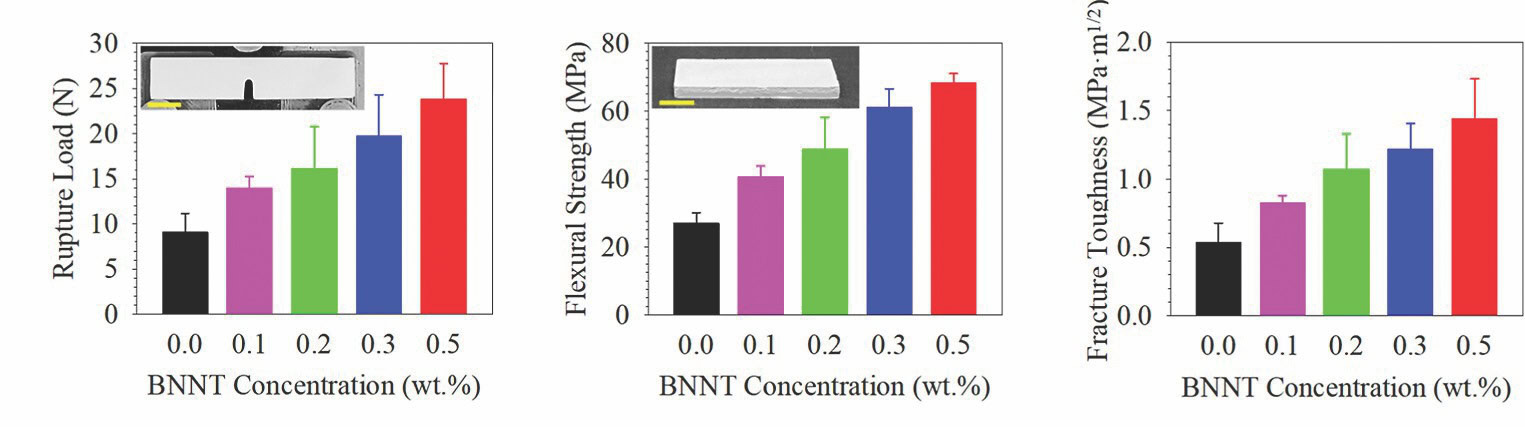

Because of their structural similarity, both BNNTs and CNTs share several key properties. Both have a Young’s modulus of more than 1 TPa, making them excellent additives for ceramics and polymers to enhance bulk material mechanical properties.4 For example, in a 100% silica ceramic matrix system, Anjum et al. showed that mechanical properties could be doubled or tripled through the addition of less than 0.5 wt.% of BNNTs (Figure 2).5 Similar success with using BNNTs as reinforcing agents has been achieved in other matrix systems.6

Figure 2. Example of how boron nitride nanotubes at low concentrations can increase the mechanical properties of ceramic matrix composites, in this case a 100% silica ceramic system.5 Credit: Anjum et al., ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. (Republished with permission)

In contrast to these mechanical similarities, BNNTs and CNTs exhibit significantly different electronic properties. Unlike the purely covalent bonds between the carbon atoms in graphite, graphene, and CNTs, the boron–nitrogen bond in hBN and BNNTs possesses a partial ionic character. This critical chemical difference theoretically promises a fundamentally insulating material, in contrast to the conductive nature of CNTs.4

Furthermore, while the chirality angle of a CNT dictates its electronic properties (either metallic or semiconducting depending on the specific atomic symmetry), the theoretical expectation for BNNTs was that it would serve as a robust electrical insulator regardless of the tube’s chirality or geometric dimensions. That expectation was due to the partially ionic bond in BNNTs forcing a wide bandgap, removing any property dependence on the chirality angle. This guaranteed electronic stability was a core scientific driver guiding early BNNT research, as it offered the possibility of a robust nanostructure without the electronic conductivity of CNTs. Many experimental studies have since confirmed these expectations.7

BNNT synthesis methods

Early synthesis methods for BNNTs mirrored those from the pioneering phase of CNT research, primarily relying on high-energy techniques, such as arc discharge. While these methods can yield large quantities of high-quality CNTs, synthesizing BNNTs using these methods often results in short tubes with high levels of impurities, such as unreacted precursor materials, nontubular BN structures, and metallic components (which are included as catalysts to contend with the thermally stable and insulative nature of the precursor materials).

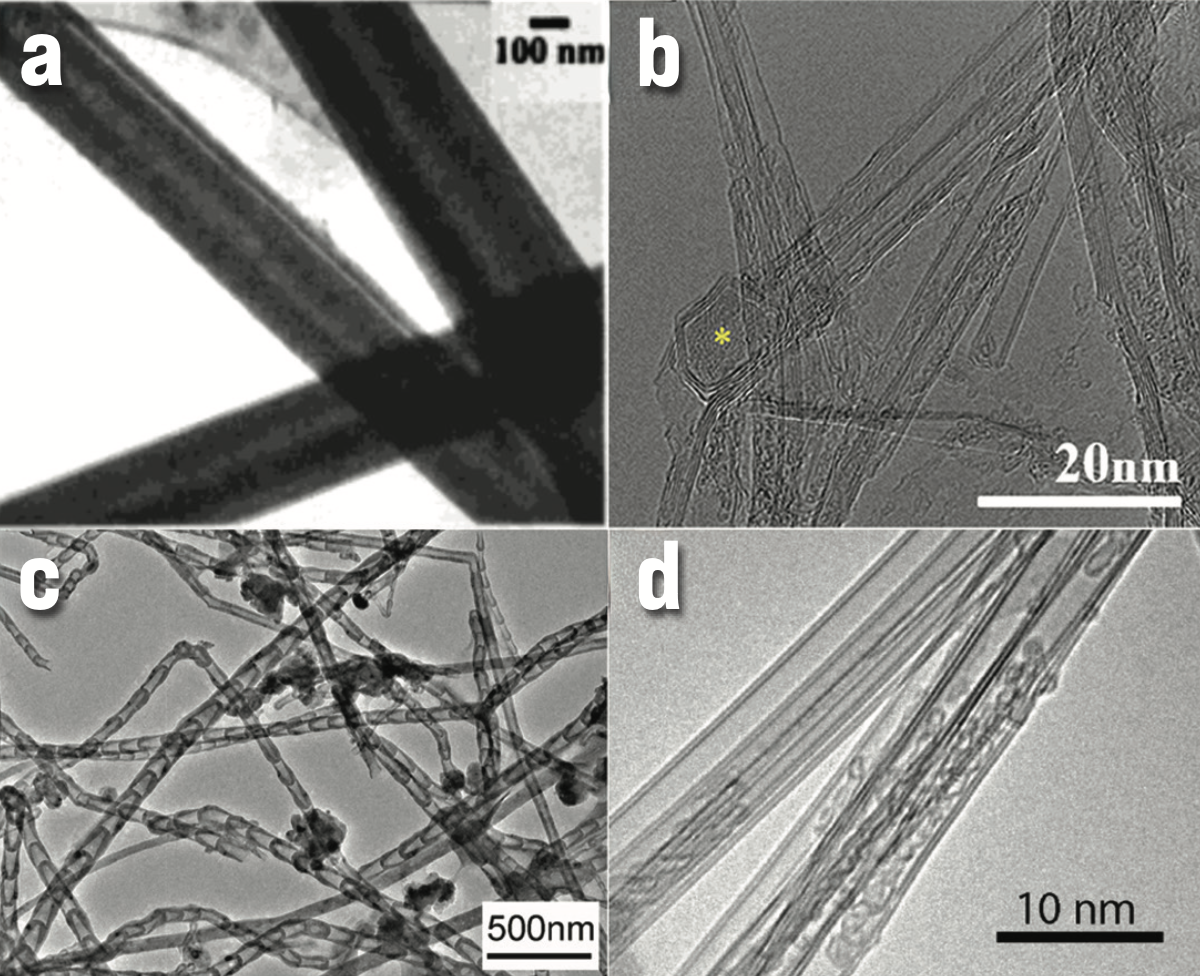

Various methods of BNNT synthesis have emerged as research and technology have progressed (Figure 3):8–14

Figure 3. Transmission electron microscopy micrographs of different boron nitride nanotube morphologies produced through various methods: a) chemical vapor deposition,8 b) laser ablation,9 c) ball milling,10 and d) thermal plasma.11 Credit: a) Shelimov and Moskovits, Chemistry of Materials (Republished with permission); b) Kim et al., Scientific Reports (CC BY 4.0); c) Li et al., Nanoscale Research Letters (CC BY 2.0); d) Fathalizadeh et al., Nano Letters (Republished with permission)

Chemical vapor deposition

This widely used method for CNT production has been adapted for BNNTs. It involves introducing volatile precursors (often containing boron and nitrogen, such as borazine) into a reaction chamber where they decompose on a heated substrate. Metal catalyst nanoparticles on the substrate act as nucleation points for tube growth. The main differences between chemical vapor deposition and other methods are the former’s reliance on a catalyst and substrate for controlled growth. The need for a catalyst leads to challenges in purifying the final BNNT product, as trace metals can impact the electrically insulating properties.

Laser ablation/evaporation

This high-energy technique uses an intense pulsed laser beam to instantaneously vaporize a solid target (typically hBN or a boron metal mixture). The resulting boron and nitrogen vapor condenses in a relatively cool, inert gas environment to form nanotubes. The rapid and extreme conditions lead to a product with high crystallinity and structural quality. This technique has a low yield, which is fine for fundamental research needing small batches of high-purity material but challenging for industrial scale-up due to the intense energy and slow kinetics of tube formation.

Ball milling and annealing

This two-step synthesis process starts with mechanical processing. High-energy ball milling grinds hBN powder into nanosized fragments with structural defects. These fragments are then subjected to a high-temperature annealing step (within a furnace) so the boron and nitrogen atoms can reorganize into tube structures. This method is often the simplest and lowest-cost approach. However, it can produce BNNTs that are short, with a higher rate of surface defects, and with a wide distribution of diameters because the initial fragmentation is less controlled than other methods.

Thermal plasma methods

These methods are the most promising for large-scale commercialization. They involve injecting precursors into an extremely hot plasma torch (often generated by an inductive coil). The plasma, reaching temperatures of 5,700°C or higher, rapidly dissociates the precursors into highly reactive boron and nitrogen species, which then quickly reassociate and cool to form long, high-quality BNNTs. This method can have high energy requirements and can leave unreacted feedstock, which requires purification.

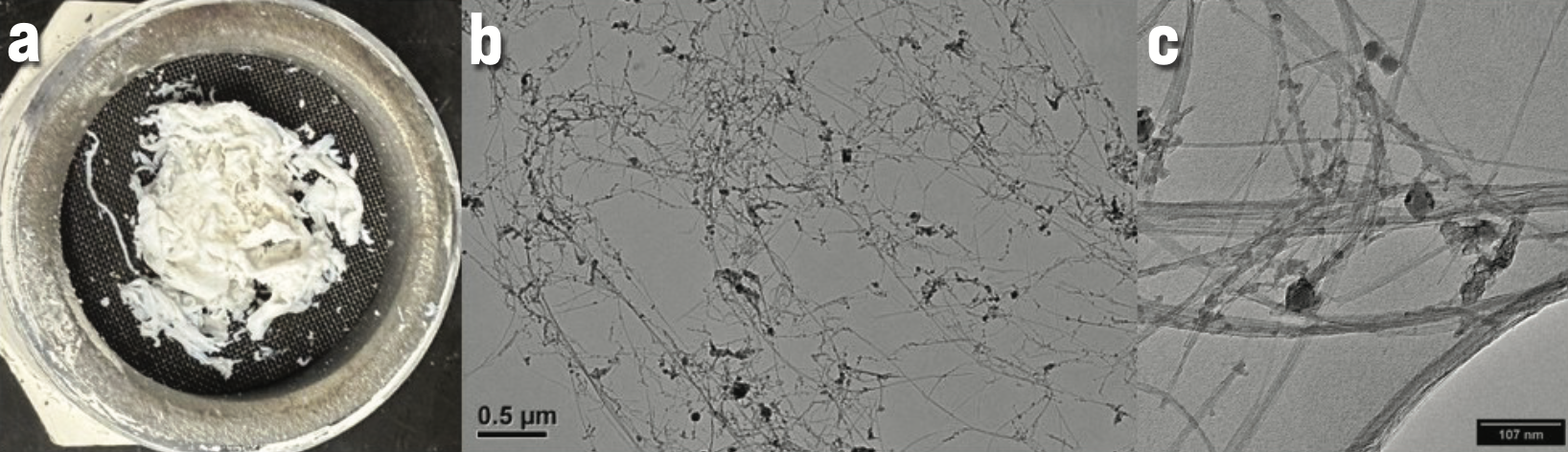

Of these methods, a thermal plasma technique called enhanced pressure inductively coupled plasma shows significant promise for overcoming many of the limitations traditionally faced in BNNT production (Figure 4). This technique, which was originally developed at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and is currently licensed and practiced by Epic Advanced Materials, does not use a metal catalyst.15 So, purification of the plasma-generated BNNTs can result in higher yields of quality tubes, as the processes used to remove metal impurities are often harsh and can generate defects in the nanotubes. Furthermore, this method has been developed to offer high production rates with aspect ratios of more than 2,000:1. Such high production rates offer the possibility of expansion into commercial uses for these materials, which have traditionally been limited to research applications due to their low rates of production.

Figure 4. (a) Image of bulk boron nitride nanotube material from Epic Advanced Materials. (b,c) Transmission electron microscopy image showing boron nitride nanotube structure as well as the presence of some impurities of boron and hBN. Credit: Epic Advanced Materials

Applications for BNNT fillers

Thermal interface materials (TIMs) are crucial for effective thermal management in electronics; however, the base polymer or grease matrices inherently suffer from poor thermal conductivity. Fillers are essential to boost heat transfer by creating continuous pathways of high thermal conductivity materials to facilitate heat flow.

The ideal filler particles for TIMs optimize the balance between achieving extremely high thermal conductivity, maintaining necessary electrical insulation, and ensuring sufficient mechanical performance. Metallic particle fillers can often lead to reduced dielectric properties undesirable for many applications and are electrically conductive, which risks short circuits. On the other hand, many existing ceramic thermal management fillers require high loading levels (from 20–50 wt.%) to achieve improvements in thermal properties, which can affect the cost, weight, and viscosity of the TIM material. So, while the resultant composite may obtain effective heat transfer properties, it can result in significant negative alteration of the original properties (e.g., Young’s modulus, tensile strength) of the matrix materials. Carbon-based fillers (e.g., graphene, CNTs) offer exceptional conductivity and light weight but are usually electrically conductive; they also face challenges with poor dispersion and high cost. Ultimately, the primary challenge is the trade-off: Materials with the highest thermal conductivity are often also electrically conductive, while maintaining electrical safety forces a reliance on less conductive ceramics.

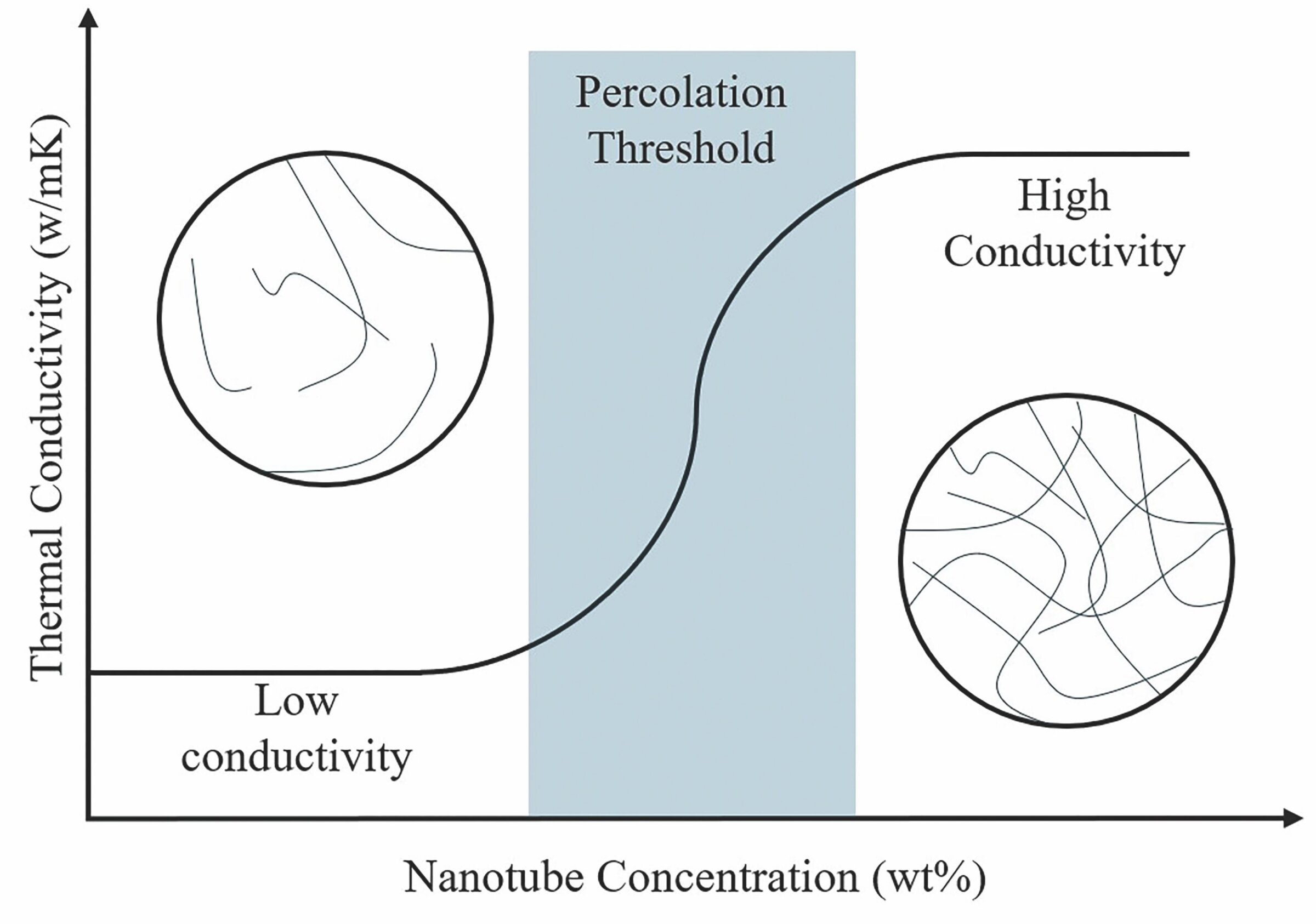

Due to their high aspect ratio, nanotubes typically have a low percolation threshold, i.e., the additive percentage at which a large change in the thermal or electrical conductivity of the bulk material is observed. As seen in Figure 5, percolation is dependent on both the concentration of particles within a matrix as well as the aspect ratio of the particles. While spherical particles can eventually form a percolation network, they require far higher concentrations than particles that are elongated. Nanotubes are essentially 1D structures, with their length orders of magnitude larger than their width, leading to bridging between networks of particles at low loadings. The low percolation threshold allows for selective tuning of thermal properties in nanotube systems while benefiting from improved mechanical properties.

Figure 5. Percolation occurs as a network of interconnected particles forms within the matrix. Controlling the particle aspect ratio and loading allows for tunable thermal properties. Credit: Epic Advanced Materials

Percolation in composite systems with an aspect ratio of 2,000:1 typically occurs at 1–3 wt.% additive concentration. If particles are added at a lower concentration, minimal effect on the thermal conductivity is observed. For higher loading levels, significant improvements in thermal conductivity and decreases in the coefficient of thermal expansion can be achieved.

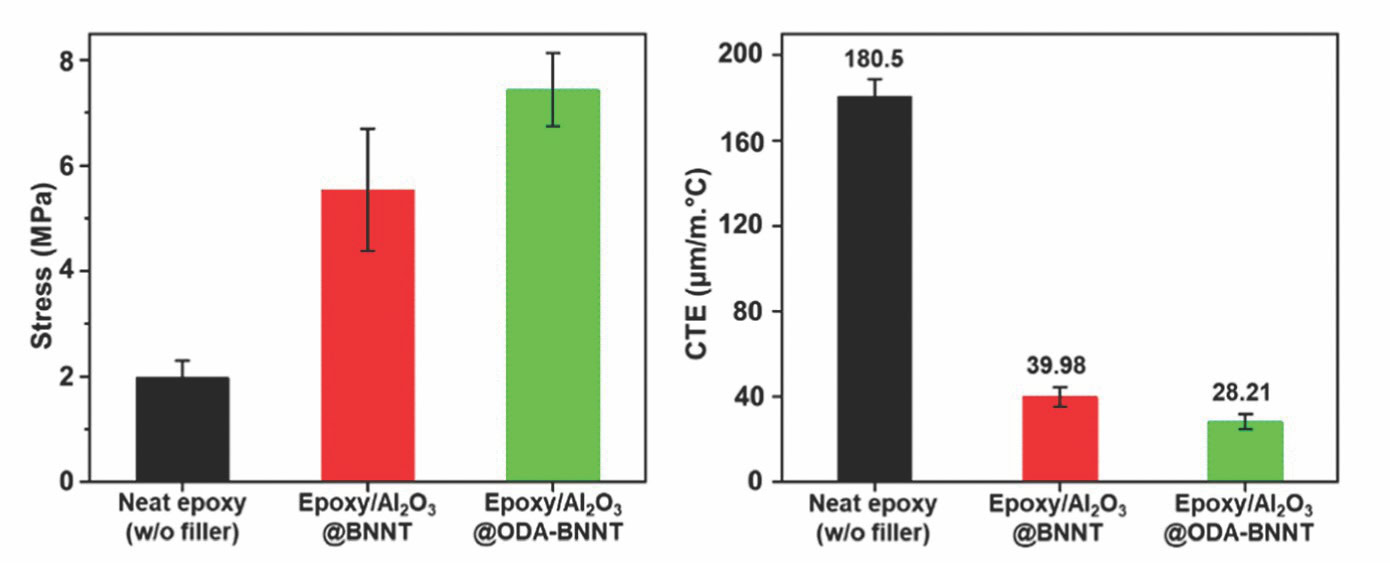

To overcome the traditional trade-off between thermal and mechanical properties, researchers frequently employ hybrid filler strategies, combining particles of different shapes or sizes to create a more robust, highly conductive 3D network at a lower required loading percentage. For example, Hanif et al. modified alumina particles to include BNNTs protruding from the surface of the ceramic particles.16 Adding BNNTs at loading levels of just 1 wt.% yielded enhancement over the effect of ceramic additive systems, increasing thermal conductivity and decreasing the coefficient of thermal expansion (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Hybrid filler strategies, such as modifying alumina particles with protruding boron nitride nanotubes, provide additional benefits in thermal conductivity and coefficient of thermal expansion.16 Credit: Hanif et al., ACS Omega (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0)

The integration of BNNTs into ceramic and composite systems can also enhance their ablation resistance due to the inherent high thermal stability and chemically nonreactive behavior of BNNTs in high-temperature, oxidizing environments. BNNTs can resist oxidation in air at temperatures of more than 850°C (CNTs only resist oxidation up to about 400°C). In a system of hybrid composite materials, Reyes et al. showed that BNNTs enhanced the survivability of the composites under exposure to a hot jet test.17 Weight loss was lowered by 14% and the flexural modulus was increased by 55%. In addition, the formation of crystalline oxides was observed, likely serving as a protective layer that shields the underlying material from the flame’s direct heat and erosive forces.

Advanced technological applications have also benefited from BNNT fillers. For example, early interest in BNNT technology was led by NASA research on applications in aerospace and extreme environments.18 Boron has an exceptionally high neutron capture cross section owing to the significant percentage of boron-10 present, whose nucleus can readily accept a neutron. The ability of BNNTs to absorb neutron radiation, combined with high thermal oxidative stability and mechanical strength, makes them ideal materials for certain aerospace applications, such as spacesuits and spacecraft. BNNTs also show superior performance in hydrogen storage, exhibiting enhanced binding strength at ambient temperature compared to CNTs, which is crucial for advancing clean energy applications.19

In the biomedical field, BNNT’s low reactivity and lack of cytotoxic properties make them suitable platforms for applications such as drug delivery, gene delivery, and neutron capture therapy; they also show potential for enhancing the properties of implants and dental resins. The catalyst-free synthesis of pressurized vapor/condenser BNNTs is particularly important for these biomedical uses, eliminating trace metal concerns introduced by the catalysts. In a National Institute of Health study, the addition of BNNTs to dental resin increased the compression strength of the composite by 46% and improved interfacial bonding and fracture resistance.20 In another study, Bohns et al. showed that the addition of BNNTs to dental sealants improved therapeutic bioactivity.21

Challenges and solutions to BNNT adoption

Based on the positive results reported in the literature and the ongoing improvements to production rates, it seems a foregone conclusion that BNNTs will spread in popularity and utility within industry. But another challenge remains before BNNTs can be widely used in large-scale production: They must be fully dispersed in a manner that preserves their high aspect ratios and avoids agglomeration or flocculation of the particles.

While their chemical nonreactivity and hydro- and oleophobic properties are a boon as an additive, these properties also complicate the dispersal of BNNTs into a variety of mediums. Unless care is taken to optimize the surface energies between the nanoparticles and the matrix, the tubes can tend toward states that minimize the energy difference. This behavior will cause agglomeration of the particles into bundles, or worse, the tubes can curl in on themselves, preferring to interact with the surface of other tubes preferentially over the matrix material.

In the former case, properties can still be imparted to the composite, but the effective mass fraction of the nanotubes will appear lower, as the tubes will operate in bundles rather than individualized particles. For the latter, much of the benefit of the particles will be lost as their aspect ratio decreases significantly. These challenges with dispersion may explain some of the wide ranges of tube fractions reported throughout literature, as poorly dispersed tubes will require a higher dosing rate to obtain target material properties.

Poor dispersibility and matrix mismatch are not challenges unique to BNNTs. Many filler materials, whether they are nano-, micro-, or macroscale, suffer from these challenges, which results in poor performance of the overall composite.

One way to combat these limitations is to provide additional surface functionalization to the filler material. This strategy incorporates chemistries or other modifications to increase compatibility with the host matrix system, thus increasing dispersibility and positive matrix interactions within the composite.

Functionalization of a filler material is most often achieved through a chemical reaction to covalently bond other groups to the filler’s surface or through the reliance on noncovalent interactions to closely associate other materials to the filler’s surface. In the case of BNNTs, the boron–nitrogen bond can be cleaved to produce reactive boron and nitrogen sites that can undergo further chemical treatment, resulting in covalent linkages to groups or materials that can enhance matrix interactions. The partial ionic nature of the boron–nitrogen bond as well as the electronic orbital structure can similarly be leveraged to noncovalently bind chemical species that also induce positive matrix interactions.

A new era of fundamental functional fillers

BNNTs are at the cusp of transforming the advanced materials landscape, offering a compelling blend of properties that surpass the limitations of conventional fillers and even their structural analog, CNTs. While synthesis and scale-up challenges have slowed their commercial adoption compared to the meteoric rise of CNTs, recent breakthroughs—notably the development of high-aspect-ratio, catalyst-free plasma production methods such as those at Epic Advanced Materials—are rapidly closing this gap, enabling large-scale availability.

As production scales and costs fall, BNNTs are poised to move beyond niche research applications to become a mainstream filler driving the next generation of lightweight, multifunctional, and high-stability composite materials.

Cite this article

E. Brown, E. A. Doud, and C. Aune, “Boron nitride nanotubes: Developing the next generation of functional fillers,” Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2026, 105(1): 26–31.

About the Author(s)

Erika Brown, Evan A. Doud, and Carl Aune are director of product development, lead research chemist, and director of business development, respectively, at Epic Advanced Materials (Thousand Oaks, Calif.). Contact Aune at carl.aune@epicbnnt.com.

About the Company

Epic Advanced Materials, founded in 2019 in Thousand Oaks, Calif., is an advanced manufacturing company specializing in nanomaterials, with a focus on boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) and ultrahigh-temperature ceramics. The company leverages proprietary artificial intelligence-driven synthesis and process optimization to scale production of high-performance nanomaterials. Its BNNT products, known for exceptional thermal stability and electrical insulation, serve as additives across aerospace, defense, electronics, and composite applications to enhance durability, strength, and overall material performance.

Issue

Category

- Electronics

- Engineering ceramics

Article References

1S. Iijima, “Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon,” Nature 1991, 354: 56–58.

2J. Zhang et al., “Atomically thin hexagonal boron nitride and its heterostructures,” Advanced Materials 2021, 33(6): 2000769.

3N. G. Chopra et al., “Boron nitride nanotubes,” Science 1995, 269(5226): 966–967.

4L. Liu, Y. P. Feng, and Z. X. Shen, “Structural and electronic properties of h-BN,” Physical Review B 2003, 68(10): 104102.

5N. Anjum et al. “Boron nitride nanotubes toughen silica ceramics,” ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2024, 2(3): 735−746.

6W.-L. Wang et al., “Microstructure and mechanical properties of alumina ceramics reinforced by boron nitride nanotubes,” J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31(13): 2277– 2284.

7J.-W. Ren et al., “Core-shell engineered boron nitride nanotubes for enhancing dielectric properties of epoxy composites,” Materials & Design 2025, 253: 113942.

8K. B. Shelimov and M. Moskovits, “Composite nanostructures based on template-grown boron nitride nanotubules,” Chemistry of Materials 2000, 12(1): 250–254.

9J. H. Kim et al., “Dual growth mode of boron nitride nanotubes in high temperature pressure laser ablation,” Scientific Reports 2019, 9: 15674.

10L. Li et al., “Mechanically activated catalyst mixing for high-yield boron nitride nanotube growth,” Nanoscale Research Letters 2012, 7: 417.

11A. Fathalizadeh et al., “Scaled synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes, nanoribbons, and nanococoons using direct feedstock injection into an extended-pressure, inductively-coupled thermal plasma,” Nano Letters 2014, 14(8), 4881–4886.

12J. J. Velázquez-Salazar et al., “Synthesis and state of art characterization of BN bamboo-like nanotubes: Evidence of a root growth mechanism catalyzed by Fe,” Chemical Physics Letters 2005, 416(4–6): 342–348.

13T. Xu et al., “Advances in synthesis and applications of boron nitride nanotubes: A review,” Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 431(3): 134118.

14S. Kalay et al., “Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes and their applications,” Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology 2015, 6(1): 84–102.

15“Method and device to synthesize boron nitride nanotubes and related nanoparticles,” United States Patent US9394632B2. Granted 19 July 2016. https://patents.google.com/patent/US9394632

16Z. Hanif et al., “Protruding boron nitride nanotubes on the Al2O3 surface enabled by tannic acid-assisted modification to fabricate a thermal conductive epoxy/Al2O3 composite,” ACS Omega 2024, 9(37): 38946–38956.

17A. N. Reyes et al., “Supersonic hot jet ablative testing and analysis of boron nitride nanotube hybrid composites,” Composites Part B: Engineering 2024, 284: 111684.

18A. L. Tiano et al., “Boron nitride nanotube: Synthesis and applications,” Proceedings of SPIE Smart Structures and Materials + Nondestructive Evaluation and Health Monitoring 2014, 9060: 906006.

19J. FN Dethan et al., “Deformation behaviors of hydrogen filled boron nitride and boron nitride – carbon nanotubes: Molecular dynamics simulations of proposed materials for hydrogen storage, gas sensing, and radiation shielding,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 57: 746–758.

20M. Patadia et al., “Enhancing the performance of dental composites with nanomaterial reinforcements via stereolithographic additive manufacturing,” Discover Nano 2025, 20(1): 149.

21F. R. Bohns et al., “Boron nitride nanotubes as filler for resin-based dental sealants,” Scientific Reports 2019, 9: 7710.

*All references verified as of Nov. 13, 2025.

Related Articles

Market Insights

Engineered ceramics support the past, present, and future of aerospace ambitions

Engineered ceramics play key roles in aerospace applications, from structural components to protective coatings that can withstand the high-temperature, reactive environments. Perhaps the earliest success of ceramics in aerospace applications was the use of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) as thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) on nickel-based superalloys for turbine engine applications. These…

Market Insights

Aerospace ceramics: Global markets to 2029

The global market for aerospace ceramics was valued at $5.3 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.0% to reach $8.2 billion by the end of 2029. According to the International Energy Agency, the aviation industry was responsible for 2.5% of…

Market Insights

Innovations in access and technology secure clean water around the world

Food, water, and shelter—the basic necessities of life—are scarce for millions of people around the world. Yet even when these resources are technically obtainable, they may not be available in a format that supports healthy living. Approximately 115 million people worldwide depend on untreated surface water for their daily needs,…